Ability to soothe role conflict and cognitive dissonance is a critical factor in addiction.

Ability to soothe role conflict and cognitive dissonance is a critical factor in addiction.

Alcohol #

What are the soothing properties of alcohol consumption in humans? #

The soothing properties of alcohol consumption are rooted in its biochemical effects on the brain, particularly its influence on neurotransmitter systems, its modulation of emotional and physiological states, and the cultural or psychological associations often tied to drinking. Here’s a breakdown of how alcohol exerts these calming effects:

- Neurochemical Action:

GABAergic Activity: Alcohol is a potent modulator of the GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) system, the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter. By enhancing GABAergic transmission, alcohol reduces neural excitability, producing feelings of relaxation and sedation. This dampening effect on the central nervous system helps alleviate anxiety and stress, fostering a sense of calm.

Dopamine Release: Alcohol also stimulates the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and reward. While dopamine is not inherently “soothing,” its release contributes to the pleasurable feelings that often accompany alcohol consumption, which can indirectly alleviate stress.

Serotonin Modulation: Alcohol affects serotonin levels, though its influence is complex and variable. Serotonin plays a key role in mood regulation, and acute alcohol consumption can enhance its mood-elevating effects, creating temporary relief from feelings of tension or sadness.

- Anxiolytic Effects:

Reduction of Acute Anxiety: Due to its depressant properties, alcohol can temporarily reduce feelings of anxiety, particularly social anxiety. By dampening overactive neural circuits associated with anxiety, alcohol can create a sense of ease, lowering inhibitions and promoting relaxation in social or stressful situations.

Muscle Relaxation: Alcohol induces physical relaxation by reducing muscle tension. This effect, combined with the neurological suppression of stress signals, contributes to the overall sensation of calmness.

- Cardiovascular Impact:

- Vasodilation: Alcohol causes the dilation of blood vessels, particularly in the skin, leading to a sensation of warmth. This vasodilation can promote a feeling of physical relaxation, as it reduces overall blood pressure and heart rate in the short term, contributing to a sense of physical and emotional soothing.

- Psychosocial and Cultural Factors:

Ritualized Relaxation: In many cultures, alcohol consumption is often linked to social rituals, celebrations, and relaxation routines (e.g., enjoying a glass of wine after a long day). The psychological associations between alcohol and unwinding contribute to its soothing effects, as these rituals can create a mental framework that predisposes individuals to feel relaxed even before the physiological effects take hold.

Cognitive Expectations: The placebo effect also plays a role in the soothing properties of alcohol. Many people expect alcohol to reduce stress and promote relaxation, and this expectation can amplify its calming effects.

- Sleep Induction:

- Sedative Properties: Alcohol is often used for its sedative effects, as it can initially help people fall asleep. It depresses central nervous system activity, which promotes drowsiness and may facilitate sleep onset, making it useful in managing insomnia or racing thoughts, albeit with caveats regarding sleep quality.

Caveats:

While alcohol can be soothing in the short term, chronic or excessive use diminishes its benefits and can exacerbate anxiety, disrupt sleep, and lead to dependence. The initial sedative and anxiolytic effects give way to more complex neurobiological changes, including the dysregulation of GABA and dopamine systems, which can increase anxiety, impair mood, and cause withdrawal symptoms.

In sum, alcohol’s soothing effects stem from its ability to modulate key neurotransmitters, suppress stress responses, and produce mild euphoria. Its psychosocial associations further augment its calming properties, though its benefits are short-lived and carry the risk of negative consequences if overused.

Tell me more about psychosocial associations of alcohol consumption? #

The psychosocial associations of alcohol consumption are deeply intertwined with cultural practices, social dynamics, and individual psychology. These associations are powerful contributors to the perceived soothing and stress-relieving properties of alcohol, often amplifying or reinforcing its effects. Understanding these associations requires examining how alcohol functions within social frameworks, its symbolic meanings, and how psychological and social expectations shape individual experiences with alcohol.

- Cultural Rituals and Traditions:

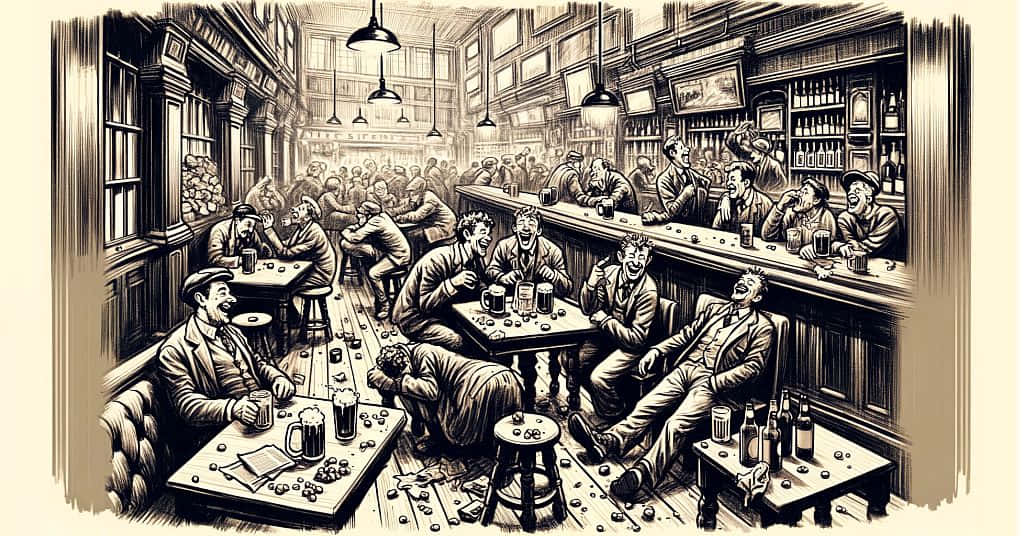

Social Bonding: Alcohol is often embedded in cultural and social rituals that foster a sense of connection, belonging, and community. From celebratory to solemn occasions, alcohol serves as a social lubricant, creating a shared experience that can reduce social anxiety and enhance feelings of togetherness. For instance, sharing a drink can signify solidarity or friendship, deepening interpersonal bonds.

Ritualized Relaxation: In many societies, alcohol consumption is a key part of unwinding rituals after work or during leisure time. This routine association with relaxation can precondition individuals to feel at ease even before they consume alcohol. The act of pouring a drink becomes a signal to the brain that it’s time to relax, creating a psychosocial expectation of calmness.

Ceremonial and Religious Functions: In some cultures, alcohol plays a role in religious or spiritual rituals (e.g., wine in Christian communion, sake in Japanese ceremonies). These contexts imbue alcohol with symbolic meanings of reverence, tradition, or unity, which can alter the psychological experience of drinking, often making it feel more profound or comforting.

- Social Context and Expectations:

Social Facilitation: Alcohol is often used to facilitate social interactions by reducing inhibitions and enhancing social confidence. The expectation that alcohol will make individuals more sociable, fun, or outgoing creates a feedback loop where the drinker, anticipating this outcome, becomes more relaxed and engaged. This effect is particularly strong in situations like parties or gatherings, where social pressures might otherwise induce stress or awkwardness.

Conformity and Peer Influence: The presence of alcohol in social settings can also create a powerful sense of group belonging. Individuals may drink not only for the physiological effects but also to conform to social norms, reducing feelings of social isolation or exclusion. In environments where drinking is normalized or expected (e.g., college parties, workplace happy hours), alcohol consumption can be a way to integrate into a group or align with shared social behaviors.

Role of Media and Advertising: The media plays a significant role in reinforcing the association between alcohol and positive social experiences. Alcohol is often depicted in movies, television, and advertising as central to celebrations, romance, and relaxation. These representations create powerful cultural narratives that link alcohol to happiness, success, and enjoyment, further reinforcing individuals’ beliefs that drinking will lead to these outcomes.

- Symbolism and Identity:

Status and Sophistication: For many, alcohol is tied to notions of sophistication or social status. Certain types of alcohol, like fine wine, aged whiskey, or craft cocktails, are symbols of refinement, affluence, or cultural capital. Drinking in specific settings, like upscale bars or dinners, can enhance one’s sense of self-esteem or belonging to a particular social class. This association with status can lead to feelings of pleasure and satisfaction that go beyond the chemical effects of alcohol itself.

Personal and Group Identity: Drinking habits are often integrated into a person’s social or cultural identity. For instance, beer may be associated with working-class culture or fraternity life, while wine or spirits might be tied to notions of elegance or intellectualism. These identities influence how people experience alcohol—drinking becomes a way to express affiliation with a particular group or self-image, which can enhance feelings of relaxation or comfort.

- Psychological Factors:

Expectation Effects (Placebo Effect): A well-documented phenomenon in alcohol research is that individuals often feel relaxed or euphoric based on their expectations of what alcohol will do, even if the actual amount consumed is minimal or a placebo. If someone believes alcohol will help them de-stress or socialize, they are more likely to experience those effects regardless of the actual dose. This demonstrates the power of psychosocial beliefs in amplifying alcohol’s soothing properties.

Stress-Relief Association: Many people come to associate alcohol with emotional relief, especially in response to chronic stress or anxiety. Over time, alcohol becomes a conditioned response to stressors—a person drinks because they expect it to help them unwind, which creates a habitual link between the two. This is both a psychological and physiological cycle: the calming effects of alcohol, combined with the relief of a familiar routine, reinforce the habit.

Coping Mechanisms: For some, alcohol serves as a form of self-medication to cope with psychological stress, trauma, or emotional pain. It is frequently used to dull negative feelings, numb emotional responses, or provide temporary escape from difficult circumstances. While this can provide short-term relief, it often leads to longer-term issues like dependence or impaired emotional regulation. Nevertheless, the initial relief contributes to the perception of alcohol as soothing or helpful in managing emotional distress.

- Norms and Gender Differences:

Gender-Specific Associations: Different gender norms often shape the psychosocial meaning of alcohol. For example, in many cultures, drinking heavily is normalized or even valorized among men, tied to masculinity, toughness, or group belonging. On the other hand, women’s drinking may be framed around moderation, sociability, or even stigmatized in some cases. These gendered dynamics influence how individuals approach alcohol consumption and the social and emotional outcomes they associate with it.

Cultural Norms: The cultural context around alcohol—whether it’s seen as a normal part of daily life (e.g., wine with meals in Mediterranean cultures) or as something that carries more restrictions (e.g., in certain religious communities)—deeply affects how soothing or stressful alcohol consumption feels. In cultures where moderate drinking is normalized, the act of drinking may carry fewer negative connotations and be seen purely as part of a relaxed social life. In more restrictive environments, drinking can be associated with guilt, rebellion, or deviance, affecting its psychosocial impact.

- Social Lubricant Effect:

Disinhibition and Risk-Taking: Alcohol lowers inhibitions, which can make people feel more comfortable taking social risks. This may involve sharing personal stories, expressing emotions, or engaging in behavior that might normally feel risky or embarrassing. The reduction of social tension through disinhibition often leads to a greater sense of emotional release or connection with others, contributing to a perception that alcohol makes social interactions smoother and more enjoyable.

Emotional Catharsis: Alcohol can sometimes be linked to emotional catharsis in group settings, where its consumption fosters an environment of openness and vulnerability. This can lead to experiences where individuals share their feelings more freely, creating deeper bonds and collective emotional relief. In such settings, alcohol acts as a psychological facilitator, allowing for an emotional release that might otherwise be inaccessible.

- Stigma and Shame:

Negative Social Associations: Conversely, the social consequences of alcohol abuse or dependency can carry stigma, potentially affecting a person’s relationship with alcohol. Societies that stigmatize excessive drinking or alcoholism may create a conflicted relationship with alcohol consumption, where it is both seen as a source of pleasure and relaxation, but also as a source of shame or risk. These psychosocial tensions can complicate the soothing properties of alcohol, particularly for individuals prone to guilt or self-criticism when drinking.

Moralization of Alcohol: In some social or religious communities, alcohol consumption is viewed as immoral or indulgent, which can affect how soothing it feels. For individuals raised with strong moral beliefs against alcohol, drinking may come with heightened feelings of guilt, which undermine its soothing effects and introduce psychological conflict.

These associations often amplify alcohol’s ability to soothe by linking its consumption to positive emotions, social belonging, and identity expression. However, they can also introduce conflict, stigma, and guilt, especially in contexts where drinking is viewed negatively. These psychosocial dynamics, along with the pharmacological effects of alcohol, shape how individuals experience its calming and stress-relieving properties.

Let’s talk about use of alcohol as a coping mechanism. Does it primarily relate to biochemistry and hormones, thus impacting amygdala, or it offers cognitive “solutions” too? #

The use of alcohol as a coping mechanism is a complex phenomenon that involves both biochemical and cognitive dimensions. It is not merely a biochemical process affecting the amygdala and related brain structures but also a cognitive and psychological strategy that individuals employ to manage stress, anxiety, and emotional discomfort. Both aspects interact and reinforce each other, making alcohol a potent, though often maladaptive, tool for coping.

- Biochemical and Hormonal Mechanisms:

GABA, Glutamate, and Neuroinhibition: Alcohol’s primary biochemical action involves enhancing the activity of GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), the brain’s main inhibitory neurotransmitter, while simultaneously suppressing glutamate, the major excitatory neurotransmitter. This neurochemical dual action reduces brain excitability, leading to a calming, sedative effect that is particularly useful for individuals seeking immediate relief from anxiety or stress. This neuroinhibitory process impacts regions like the amygdala, which is critical in processing fear, anxiety, and emotional responses.

Amygdala Suppression: The amygdala, central to the brain’s fear and anxiety circuits, is highly sensitive to the effects of alcohol. By dampening its activity, alcohol can suppress the emotional intensity associated with fear and anxiety. This biochemical “numbing” reduces the perception of threat or danger, contributing to the immediate sense of relief that alcohol provides. This is particularly appealing to individuals dealing with chronic stress, social anxiety, or trauma, where hyperactivity of the amygdala is often present.

Dopamine and Reward System: Alcohol also stimulates the release of dopamine in the brain’s reward pathway, primarily in the nucleus accumbens. This reinforces the pleasurable sensations associated with alcohol use, creating a positive feedback loop that can lead to habitual consumption as a means of coping. The biochemical reward reinforces the cognitive expectation that alcohol provides emotional relief, making it a preferred method for dealing with discomfort.

Stress-Response System (HPA Axis): Alcohol also affects the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the body’s stress response by regulating cortisol and other stress hormones. Acute alcohol consumption can temporarily reduce the body’s cortisol levels, leading to a sense of relief from stress. Over time, however, chronic alcohol use dysregulates the HPA axis, making it less responsive to stress and leading to higher baseline levels of anxiety. This, in turn, perpetuates the need for further alcohol consumption to cope, creating a cycle of dependence.

- Cognitive and Psychological Dimensions:

Beyond its biochemical effects, alcohol as a coping mechanism also offers cognitive “solutions” to emotional and psychological stress. These cognitive aspects can be as significant as the biochemical ones, contributing to the psychological relief that alcohol provides.

a. Emotion Regulation and Avoidance:

Cognitive Escape and Emotional Numbing: For many people, alcohol serves as a tool for cognitive escape—a way to avoid confronting difficult emotions or stressors. By dulling emotional responses and suppressing self-awareness, alcohol allows individuals to temporarily evade unpleasant thoughts or feelings. This form of emotional numbing is particularly appealing to individuals who struggle with emotional regulation, as it provides a temporary break from overwhelming emotional experiences.

Short-Term Cognitive Relief: Alcohol can offer a sense of cognitive relief by narrowing attention and decreasing the cognitive load. Alcohol impairs higher-order executive functions (such as working memory, reasoning, and planning), reducing the ability to dwell on worries or stressors. This mental narrowing effect leads to the perception that problems are more manageable or distant, creating a sense of cognitive reprieve, even if temporarily.

b. Cognitive Distortions and Maladaptive Beliefs:

Reinforcement of Maladaptive Thinking: Over time, individuals may develop cognitive distortions related to alcohol use, such as the belief that drinking is the most effective or perhaps only way to manage stress or emotional discomfort. These maladaptive beliefs contribute to the continued use of alcohol as a coping strategy, despite its negative long-term consequences. People may come to believe that they need alcohol to handle difficult situations or emotions, reinforcing a cycle of avoidance.

Cognitive Dissonance and Justification: Cognitive dissonance often arises when individuals recognize the negative consequences of their alcohol use (e.g., poor health, strained relationships) but continue to drink. To reduce the discomfort of this dissonance, individuals may employ justifications or minimize the harm of alcohol (“It helps me relax,” “Everyone drinks when they’re stressed”). These justifications help maintain the coping behavior, allowing the person to continue using alcohol without confronting its negative impact.

c. Alcohol as a Social Coping Mechanism:

Social and Cognitive Frameworks: Alcohol also provides a social coping framework, especially in cultures where drinking is associated with relaxation, celebration, or emotional release. In these contexts, drinking can offer a cognitive shortcut for managing social stress, where individuals feel more socially competent or at ease when they drink. The cognitive association between alcohol and reduced social tension can lead to alcohol becoming a habitual social coping tool, reinforcing its use in stressful situations.

Reduced Cognitive Barriers: Alcohol lowers cognitive barriers to emotional expression, facilitating more open communication and emotional release in social settings. This can be perceived as a form of cognitive “solution” in cases where individuals struggle to express emotions when sober. However, this coping mechanism can become problematic, as reliance on alcohol for emotional openness may inhibit the development of healthier coping strategies.

d. Impaired Problem-Solving and Decision-Making:

Impaired Cognitive Flexibility: Alcohol reduces cognitive flexibility, impairing a person’s ability to effectively problem-solve or engage in adaptive coping strategies. While alcohol may offer immediate relief by numbing distressing emotions or dulling awareness of stressors, it also impairs higher-order thinking, which could otherwise lead to the development of more constructive or long-term coping mechanisms.

Avoidance Coping Strategy: By focusing on short-term emotional relief, alcohol use as a coping mechanism aligns with avoidance coping strategies, where individuals disengage from addressing the root causes of their stress. This avoidance prevents cognitive restructuring, or the process of changing negative thought patterns into more adaptive ones, reinforcing emotional dependence on alcohol without resolving the underlying issues.

- Cognitive Solutions and Learned Coping:

While alcohol is primarily an avoidance-based coping mechanism, there are some cognitive dynamics at play that suggest people use alcohol in a problem-solving capacity, albeit maladaptive. People often develop a learned association between alcohol and emotional relief, effectively viewing alcohol as a “solution” to certain emotional problems. For instance:

Expectancy Theory: The belief that alcohol will reduce stress or help them cope with emotional pain creates a cognitive framework in which alcohol is seen as a reliable tool for managing discomfort. This expectancy enhances the cognitive reinforcing effect of drinking, as individuals expect to feel better and may perceive that they do, at least temporarily.

Ritualization of Coping: For some, drinking becomes a ritualized cognitive response to stress—after a long day at work, they may automatically reach for alcohol as part of a well-established coping routine. This routinization can lead to alcohol becoming a habitual “cognitive solution” to stress, bypassing more adaptive coping strategies that require conscious effort and emotional processing.

- Long-Term Cognitive Consequences:

Cognitive Impairment: Chronic alcohol use can lead to long-term cognitive impairments, including issues with memory, attention, and executive functioning. These deficits can compound emotional distress, as individuals lose the cognitive flexibility and problem-solving skills necessary to engage in adaptive coping. The cycle of impaired cognitive function and emotional distress reinforces the reliance on alcohol as a coping tool.

Decreased Cognitive Control: Over time, chronic alcohol use reduces cognitive control over emotional regulation, meaning that individuals may become less able to manage their emotions without alcohol. This erodes resilience and increases dependence on alcohol as a coping strategy, leading to more entrenched patterns of avoidance and emotional suppression.

The use of alcohol as a coping mechanism involves a combination of biochemical effects (neurotransmitter modulation, amygdala suppression, and reward pathway activation) and cognitive dimensions (emotion regulation, avoidance strategies, and social frameworks). While the biochemical aspects provide immediate relief from stress and anxiety, the cognitive elements reinforce alcohol use as a maladaptive solution to emotional problems. Together, these factors create a potent cycle of avoidance, emotional suppression, and reliance on alcohol as a “quick fix” for stress, often at the expense of long-term emotional health and cognitive resilience.

What do we call a “social framework”? Can an individual maintain multiple social frameworks continuously - a metaphor that comes to mind is a child spending the weekend with a Sunday father and comfortably coping with an entirely different set of household rules? #

A “social framework” refers to the set of norms, values, expectations, and behaviors that govern interactions within a specific social context or group. These frameworks shape how individuals perceive themselves, how they behave, and how they relate to others within that context. Social frameworks are often defined by cultural, familial, institutional, or situational factors and help people navigate their social roles.

Core Aspects of a Social Framework:

Norms and Expectations: Implicit or explicit rules that guide appropriate behavior in a particular social group or environment (e.g., formal workplace behavior vs. relaxed family settings).

Roles and Identities: The roles people assume (e.g., employee, parent, friend) and the associated expectations for how they should act within each role. Power Dynamics and Hierarchies: How authority or influence is distributed within the group (e.g., parent-child hierarchy, employer-employee relationships). Communication Styles: Accepted modes of interaction, including verbal and non-verbal cues, and how individuals are expected to express emotions, opinions, or disagreement.

Shared Values and Beliefs: The collective attitudes and moral principles that underpin the group’s interactions (e.g., communal vs. individualistic values). Can Individuals Maintain Multiple Social Frameworks?

Yes, individuals can and often do maintain multiple social frameworks simultaneously. Human behavior is highly adaptable, allowing people to shift between different sets of norms and expectations depending on the context. This ability to adjust is rooted in the social concept of “role flexibility” and is a natural part of navigating different environments.

In your metaphor of a child comfortably coping with different sets of household rules (e.g., weekends with a “Sunday father” who may have distinct rules and routines from the primary household), the child is effectively managing two distinct social frameworks. This adaptability relies on context-specific behavioral shifts, where the child intuitively understands that different rules apply in each household and adjusts accordingly.

Psychological and Social Mechanisms Enabling Multiple Frameworks:

Role Switching: People often switch roles based on social context. For instance, someone might be a nurturing parent at home but an assertive manager at work. Role switching allows individuals to compartmentalize their behaviors and emotions to fit the expectations of different environments.

Code-Switching: A concept often discussed in linguistics, code-switching can also be applied more broadly to social behavior. It refers to the ability to adjust one’s speech, behavior, and interaction style depending on the social setting. For example, a child might speak more formally with one parent and more casually with the other.

Cognitive Flexibility: This refers to the brain’s ability to adapt and switch between different mental frameworks or strategies. Individuals with high cognitive flexibility can shift between multiple social frameworks more easily, as they are better equipped to handle changing social demands and expectations without stress or confusion.

Internalized Rules and Socialization: From a young age, individuals learn to internalize the specific norms and expectations of different social contexts. A child who spends time in two households may develop a strong sense of when to apply which set of rules, similar to how an adult understands different rules for professional versus personal life.

Emotional Regulation: Managing different social frameworks often requires emotional regulation. A child may experience different emotional climates in each household—one that’s more relaxed and playful, and another that’s stricter and more formal. The ability to regulate emotions based on the environment is key to navigating these shifts.

Potential Tensions or Conflicts:

While it’s possible to maintain multiple social frameworks, this dynamic can sometimes lead to role conflict or cognitive dissonance, especially when the expectations from different frameworks clash. For example, a child might experience confusion or stress if the rules in one household are not only different but also in direct opposition to those in the other (e.g., one household is highly permissive, while the other is very strict).

However, in many cases, individuals find ways to compartmentalize these frameworks, maintaining separate mental and emotional boundaries for each context. This allows them to successfully navigate and manage different environments without internal conflict.

Metaphor of the Child with Two Households:

Your metaphor of the child is apt for understanding how individuals manage multiple social frameworks. A child who spends time with a “Sunday father” might experience different rules, routines, and emotional climates compared to their primary household. If the child is able to shift smoothly between these environments, they demonstrate:

Contextual Intelligence: Understanding when and how to adapt their behavior according to different sets of social expectations.

Role Fluidity: Navigating the differing roles they play in each household (perhaps being more autonomous in one and more dependent in the other).

Emotional Resilience: Coping with the varying emotional demands of each household, possibly using different strategies to gain approval or meet expectations in each setting.

A social framework is the set of norms, roles, and expectations that shape how individuals interact in specific contexts. People can maintain multiple frameworks simultaneously, drawing on cognitive flexibility, role switching, and emotional regulation to manage different environments effectively. The child with two households exemplifies this ability to navigate distinct social realities, learning to adapt to different sets of rules and social expectations while maintaining emotional balance. This capacity to shift between frameworks is a fundamental aspect of human social behavior.

Alcohol is probably able to soothe role conflict and cognitive dissonance - how prominent is this facet in fostering alcohol addiction? #

Alcohol’s ability to soothe role conflict and cognitive dissonance plays a significant role in fostering addiction, especially when individuals rely on alcohol as a coping mechanism for these psychological tensions. The self-medicating properties of alcohol—particularly its capacity to blunt the emotional discomfort that arises from conflicting roles or dissonant beliefs—create a feedback loop where drinking becomes a primary strategy for managing internal conflict. Over time, this reliance can contribute to the development of alcohol addiction.

- Role Conflict and Alcohol as a Coping Mechanism

Role conflict occurs when a person experiences tension between the expectations of two or more roles they occupy, such as being a parent and a high-stakes professional, or having different behavioral demands from various social groups. This conflict can generate considerable stress, anxiety, and frustration, as individuals may feel unable to meet the demands of all their roles simultaneously.

Alcohol’s soothing properties—particularly its capacity to inhibit cognitive control and alleviate emotional distress—make it a tempting way to manage the emotional fallout of role conflict. For example:

Someone facing the stress of balancing work and family life may turn to alcohol to escape the feelings of inadequacy or failure associated with not meeting expectations in one or both roles.

Alcohol can blur the boundaries between conflicting roles, offering temporary relief by making the individual less conscious of the pressures and constraints each role imposes.

By numbing emotional tension, alcohol gives the illusion of reconciling or simplifying the conflicts between different roles, allowing the person to avoid confronting the deeper issues. This immediate relief creates a strong association between alcohol and conflict resolution, reinforcing its use whenever role conflict arises.

- Cognitive Dissonance and Alcohol Use

Cognitive dissonance refers to the psychological discomfort experienced when an individual holds two or more contradictory beliefs, values, or attitudes. The tension arises from the clash between these opposing elements, and people are naturally motivated to reduce this discomfort through various strategies, including justifying, rationalizing, or changing behaviors.

Alcohol as a Dissonance Reducer: Alcohol is highly effective at reducing cognitive dissonance because it impairs higher-order cognitive functions, such as critical thinking and self-reflection. When individuals are confronted with dissonance—for example, if they act against their values (e.g., lying or compromising their integrity), or fail to live up to expectations (e.g., underperforming at work)—alcohol can provide immediate relief by dulling the uncomfortable awareness of the inconsistency.

Emotional Avoidance: Rather than confronting the source of dissonance and working through it cognitively or emotionally, individuals can use alcohol to numb the psychological tension, allowing them to continue in contradictory behaviors without addressing the underlying issues. This avoidance strategy is reinforced by alcohol’s depressant effects on the brain, especially its impact on the prefrontal cortex (responsible for rational thought and decision-making) and amygdala (involved in emotional processing and threat detection).

Over time, if alcohol becomes the primary means of managing dissonance, individuals will increasingly depend on it to avoid the emotional discomfort of conflicting beliefs or behaviors. This can create a cycle of avoidance and self-deception, where the individual drinks to escape from self-awareness or moral conflict, fostering alcohol dependence.

- The Role of Alcohol in Managing Identity Fragmentation

Alcohol’s ability to ease role conflict and cognitive dissonance is particularly relevant when people face identity fragmentation—a state where they feel divided or incoherent due to conflicting aspects of their identity (e.g., being both a nurturing parent and a high-powered executive). The fluidity of identity can be difficult to manage, especially when different social frameworks or contexts demand incompatible behaviors.

Temporarily Unifying Identity: Alcohol can provide a temporary sense of identity coherence by blunting the awareness of conflicting roles or beliefs, allowing individuals to feel more at peace with their fractured identity. The immediate sense of relaxation and detachment can make it seem as though the tension between different aspects of the self has been resolved, even though the underlying issues remain.

Social Role Dissolution: Alcohol often dissolves the strict boundaries between roles, particularly in social settings. For example, someone who feels pressure to maintain professionalism might use alcohol to relax those constraints in a social context, finding relief from the tension between their work persona and their personal self. However, this reliance on alcohol to mediate these identity tensions can become addictive as the individual increasingly turns to drinking to manage emotional and social stressors.

- Alcohol and Emotional Regulation in Role Conflict

Role conflict and cognitive dissonance can lead to chronic emotional dysregulation—where individuals feel they cannot effectively manage their emotional responses to competing demands or internal contradictions. In such cases, alcohol is appealing because it acts as an immediate emotional regulator, providing quick relief from the anxiety, frustration, or guilt associated with dissonant roles or beliefs.

Anxiolytic Effects: Alcohol’s anxiolytic (anti-anxiety) properties, mediated through its effects on GABAergic neurotransmission, are particularly useful in reducing the stress and unease associated with role conflict. By dampening the amygdala’s activity, alcohol diminishes emotional reactivity, making individuals less sensitive to the tensions inherent in their competing roles.

Euphoria and Reward: The dopaminergic effects of alcohol can mask negative emotions by inducing a temporary sense of euphoria or pleasure. This neurochemical reward reinforces the use of alcohol in stressful or emotionally conflicted situations, as individuals learn to associate drinking with emotional relief and a reduction in cognitive tension.

- The Feedback Loop and Addiction

The cycle of using alcohol to cope with role conflict and cognitive dissonance can lead to addiction through several reinforcing mechanisms:

Negative Reinforcement: As individuals repeatedly turn to alcohol to alleviate stress or internal conflict, they experience negative reinforcement, where the removal of unpleasant emotions through alcohol use strengthens the habit. Each time alcohol is used to reduce the discomfort of cognitive dissonance or role conflict, it becomes more entrenched as a coping strategy.

Tolerance and Escalation: Over time, individuals may develop tolerance to alcohol’s effects, requiring more alcohol to achieve the same emotional relief. As the brain adapts to chronic alcohol use, the initial soothing properties diminish, leading to escalated consumption and greater dependency.

Cognitive and Emotional Dependence: Beyond physical dependence, individuals may develop a strong cognitive dependence on alcohol as the primary or sole method of managing role conflict or emotional discomfort. The habitual reliance on alcohol reduces their ability to develop healthier coping mechanisms, which further reinforces the addiction cycle.

- The Escalation of Role Conflict and Dissonance in Addiction

Increased Role Conflict from Alcohol Use: Paradoxically, as alcohol use becomes more habitual, it can create or exacerbate the very role conflicts it was initially used to soothe. For instance, alcohol dependence can impair a person’s ability to fulfill responsibilities at work, in relationships, or as a parent, thereby increasing stress and role conflict. This escalation of conflict can drive further drinking, as the individual seeks to numb the mounting pressures caused by their alcohol use.

Amplified Cognitive Dissonance: As addiction progresses, individuals may experience increased cognitive dissonance related to their drinking behavior, especially if it conflicts with their self-image, values, or social roles. For example, someone who values responsibility and self-control may experience significant guilt or shame about their drinking, but rather than confronting this, they may use more alcohol to suppress these negative emotions, deepening the cycle of addiction.

Alcohol’s ability to soothe role conflict and cognitive dissonance is a critical factor in the development of addiction. By providing temporary relief from the emotional and psychological discomfort associated with conflicting roles or contradictory beliefs, alcohol becomes a powerful tool for avoidance coping. This reliance on alcohol as a cognitive and emotional regulator can lead to addiction, as the individual becomes increasingly dependent on its effects to manage internal conflict. Over time, alcohol use can exacerbate the very role conflicts and cognitive dissonances it was initially used to alleviate, creating a vicious cycle that fosters deeper psychological dependence and addiction.

Lastly, as a thought experiment, how would alcohol help Lady Macbeth to cope with her predicament? #

If Lady Macbeth were to turn to alcohol to cope with her predicament, it would provide her temporary relief in several psychological and emotional domains, though with significant consequences. Her predicament—rooted in guilt, ambition, power, and the unraveling of her mental state—would see alcohol acting as a short-term emotional and cognitive escape, but in the longer term, it would likely exacerbate her turmoil. Here’s how alcohol could function in this context:

- Dulling Guilt and Emotional Numbing:

Lady Macbeth’s overwhelming guilt after the murder of King Duncan is a central feature of her unraveling. Alcohol, with its GABAergic (inhibitory) effects on the brain, would temporarily reduce her anxiety and feelings of remorse by numbing her emotional responses. By suppressing the activity in the amygdala, alcohol would blunt the intense emotional impact of her guilt, offering her brief moments of relief from the tormenting thoughts of blood on her hands (“Out, damned spot!”). This emotional numbing would allow her to avoid confronting the psychological horror of her actions, at least temporarily, just as alcohol often acts as a way to suppress or avoid painful emotions.

- Suppressing Cognitive Dissonance:

Lady Macbeth experiences cognitive dissonance between her role as a ruthless instigator of murder and her inherent moral awareness. She drives her husband to commit regicide, yet she cannot escape the psychological toll of her ambition clashing with her moral compass. Alcohol could serve as a temporary solution to this dissonance by impairing her ability to think critically about her contradictory desires and actions. Alcohol would provide an escape from self-reflection, dulling the part of her mind that forces her to face the inconsistency between her moral identity and her lust for power. By drinking, she might be able to suppress the inner conflict between her ambition and her conscience, avoiding the need to resolve the tension between these two aspects of herself.

- Relief from Role Conflict:

Lady Macbeth’s role as both a loyal wife and an ambitious political manipulator is a form of role conflict. On one hand, she seeks power for herself and her husband, pushing Macbeth to fulfill the witches’ prophecy. On the other hand, she tries to manage the expectations of being a noblewoman, a wife, and eventually, a queen. The stress of these competing roles could drive her to alcohol, as it could offer temporary relief by dissolving the boundaries between these conflicting roles.

Alcohol would reduce the cognitive strain of managing these roles, allowing her to exist in a space where the emotional and psychological demands of her conflicting identities are temporarily softened.

- Easing Anxiety and Sleeplessness:

In the play, Lady Macbeth famously suffers from sleeplessness and nightmares, haunted by the murder of Duncan and the subsequent guilt. Alcohol, as a sedative, would offer some short-term relief from insomnia and anxiety by inducing drowsiness and relaxation. The anxiety-driven insomnia that she experiences would be temporarily alleviated, as alcohol would inhibit her prefrontal cortex, reducing rumination and the constant mental replaying of her crimes. However, while alcohol might help her fall asleep, it would likely worsen her overall sleep quality, deepening her psychological deterioration over time.

- Dissociating from Reality:

Alcohol’s effect on cognitive processing would allow Lady Macbeth to dissociate from the reality of her situation. It would impair her ability to fully comprehend the gravity of what she has done, providing her with a psychological buffer from the horrors she has unleashed. This dissociation would grant her a false sense of detachment from the consequences of her actions, temporarily shielding her from the weight of her guilt, ambition, and moral collapse.

- Social Facilitation and False Confidence:

As Lady Macbeth spirals deeper into her predicament, she loses control over the situation she set into motion. Alcohol could provide her with a false sense of confidence, enabling her to maintain her composure in public or during moments when she needs to mask her inner turmoil. It might help her project the air of control and nobility she once had, even as her mind deteriorates.

Additionally, alcohol could act as a social lubricant, helping her navigate the increasingly strained social interactions with her husband and their court. This false sense of control, however, would only last as long as the effects of alcohol, and would likely leave her even more vulnerable once sobriety returns.

The Darker Side: Alcohol as a Catalyst for Decline

While alcohol could provide Lady Macbeth with temporary respite from her inner torment, the longer-term consequences would likely be disastrous. Alcohol use as a coping mechanism would accelerate her mental and emotional unraveling:

Exacerbation of Paranoia and Hallucinations: Given that Lady Macbeth already experiences hallucinations (such as the imagined blood on her hands), alcohol could worsen her psychotic symptoms, increasing her susceptibility to further hallucinations and paranoia. Alcohol-induced cognitive impairment could make it harder for her to distinguish between reality and delusion, accelerating her descent into madness.

Intensified Guilt and Depression: Alcohol’s effects are temporary, and upon sobering up, Lady Macbeth would likely experience an intensified sense of guilt and despair. The emotional suppression that alcohol offers would wear off, leaving her to face the consequences of her actions with heightened sensitivity, potentially driving her toward greater desperation and despair.

Physical Deterioration and Dependency: If Lady Macbeth were to rely on alcohol continuously to manage her emotional state, she would risk developing a physical dependency, further eroding her physical and mental health. Alcoholism would only compound her mental fragility, leading to further decline in her already deteriorating state.

In sum, alcohol could provide Lady Macbeth with temporary emotional numbing, cognitive dissociation, and relief from anxiety related to her role conflict and cognitive dissonance. However, these effects would be fleeting and ultimately detrimental, as they would prevent her from confronting the source of her inner turmoil. Her reliance on alcohol would likely accelerate her psychological and physical deterioration, exacerbating her guilt, hallucinations, and madness. While alcohol could momentarily soothe her predicament, it would also deepen the abyss of moral and emotional destruction she finds herself in, hastening her tragic downfall.