Subclinical inability to identify and describe emotions in oneself or others.

Subclinical inability to identify and describe emotions in oneself or others.

Alexithymia #

Let’s talk about alexithymia? #

Alexithymia is a psychological construct that refers to a subclinical inability to identify and describe emotions in oneself or others. The term, derived from Greek, literally means “no words for emotions” (from a = lack, lexis = word, and thymos = emotions or mood). First introduced in the 1970s by Peter Sifneos, the concept has since gained prominence in both clinical psychology and psychosomatic medicine due to its association with various emotional and psychosomatic disorders.

Key Characteristics of Alexithymia

Individuals with alexithymia typically display the following traits:

Difficulty in Identifying Emotions: They struggle to recognize or differentiate between emotional states, often confusing physical sensations (like fatigue or stress) with emotions.

Difficulty Describing Emotions: Even when aware of their emotional state, those with alexithymia have trouble verbalizing or articulating what they are feeling. They often lack the emotional vocabulary to convey their inner experiences.

Externally Oriented Thinking: People with alexithymia tend to focus on external, practical matters rather than their internal emotional landscape. Their thinking is often concrete and detail-oriented, with little attention given to subjective feelings or imaginative experiences.

Limited Imaginative Life: There is often a reduced capacity for fantasizing or engaging in creative imagination, which is closely tied to their difficulty in emotional processing.

Poor Emotional Regulation: As a consequence of these deficits, individuals may have difficulty managing emotional responses in a socially adaptive way, leading to issues in interpersonal relationships.

The Spectrum of Alexithymia

Alexithymia is conceptualized as existing on a spectrum, with some individuals showing mild tendencies and others demonstrating more pronounced traits. It’s not a standalone psychiatric disorder but rather a feature or dimension present in various mental health conditions. Notably, alexithymia is often found in individuals with:

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Research suggests a higher prevalence of alexithymia among individuals with autism. While the two conditions overlap, they are distinct. Not all individuals with ASD exhibit alexithymia, and not all alexithymic individuals are on the autism spectrum.

Depression and Anxiety: Individuals with mood disorders often show heightened levels of alexithymia, particularly in the inability to process their negative emotions.

Psychosomatic Disorders: Historically, alexithymia was closely linked to psychosomatic medicine, where emotional dysregulation was thought to contribute to physical symptoms. Patients with conditions like irritable bowel syndrome, chronic pain, or hypertension may show alexithymic tendencies, leading some to speculate that these individuals “somatize” their emotions due to their inability to process them psychologically.

Substance Use Disorders: There is also a notable association between alexithymia and addiction. Some theorists propose that individuals with alexithymia may use substances as a means of regulating their affect or filling an emotional void.

Neurological and Psychological Correlates

Research on the neurological underpinnings of alexithymia has found links to dysfunctions in several brain regions:

The Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC): This area of the brain, associated with emotional awareness and the regulation of emotional responses, is often found to be underactive in people with alexithymia.

The Insular Cortex: The insula plays a role in the subjective awareness of bodily sensations, including the internal physiological states associated with emotion (interoception). Individuals with alexithymia may show reduced activity in this region, potentially explaining their difficulties with emotional awareness.

Prefrontal Cortex Dysregulation: Some studies suggest that individuals with alexithymia show abnormal activity in the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in higher-order cognitive processes, including emotional regulation.

Causes of Alexithymia

There is no singular cause of alexithymia, but rather, it appears to result from a complex interaction of genetic, environmental, and developmental factors:

Genetic Factors: Twin studies suggest a moderate heritability for alexithymia, indicating that there may be a genetic predisposition towards difficulty with emotional processing.

Early Childhood Experiences: Emotional neglect or trauma in early life has been implicated in the development of alexithymic traits. Children who grow up in environments where emotions are not expressed or valued may fail to develop the necessary emotional literacy to understand and describe their own feelings.

Cultural Influences: Certain cultures or subcultures may discourage the expression of emotion, particularly in males. This cultural stoicism can contribute to the development of alexithymia, as individuals may not have been socialized to engage with or express their emotional experiences.

Alexithymia and Interpersonal Relationships

People with alexithymia often experience challenges in relationships due to their difficulties in understanding their own and others’ emotional states. They may come across as emotionally distant, indifferent, or unempathetic, leading to frustrations in their personal and professional interactions. Romantic partners of alexithymic individuals often report feeling emotionally disconnected, which can cause strain in the relationship.

However, not all alexithymic individuals are devoid of emotional capacity; many may care deeply about others but simply struggle to communicate or comprehend their own emotions in a way that aligns with typical social expectations.

Treatment and Management

Addressing alexithymia is challenging, as traditional therapeutic approaches that rely on introspection and emotional insight may not be effective for this population. However, some strategies have been shown to help:

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): While the emotionally introspective aspects of therapy may be challenging, CBT’s focus on observable behavior and cognitive restructuring can offer benefits by helping individuals recognize patterns in their behavior that are linked to emotional states.

Mindfulness Training: Mindfulness can improve emotional awareness by encouraging individuals to focus on the present moment and become more attuned to their bodily sensations and mental states.

Emotion-Focused Therapy: Some approaches within this therapeutic framework aim to help individuals increase their emotional awareness and learn the language of emotion. Although progress may be slower for those with alexithymia, incremental improvements in emotional recognition can occur over time.

Interpersonal Therapy: Since interpersonal problems often result from alexithymia, therapies focused on communication skills and understanding relational dynamics can be beneficial. The goal is not necessarily to “cure” alexithymia but to help individuals function better within their relationships.

Is there a methodology relying on thought processes that can be used to recognize emotions? #

Yes, there are several methodologies grounded in cognitive and psychological approaches that help individuals recognize and understand emotions, particularly useful for those who struggle with emotional awareness, such as individuals with alexithymia. These methodologies aim to cultivate emotional intelligence through structured thought processes and systematic engagement with one’s emotional experiences. Below are some prominent strategies and thought-process-based techniques:

1. Cognitive Labeling and Emotional Differentiation

Method: This approach involves deliberately naming or labeling emotions as they occur, which helps in consciously identifying and categorizing different emotional states. Many people, especially those with alexithymic tendencies, struggle with distinguishing between subtle emotional nuances.

How it Works: Individuals are encouraged to pause and reflect on their physical sensations, thoughts, and the context surrounding them to pinpoint their emotional state. Once an emotion is identified, the next step is to apply a label (e.g., “I am feeling anxious” or “I am feeling disappointed”). This process of assigning verbal labels to emotional experiences fosters emotional clarity and increases one’s emotional vocabulary.

Why it Helps: Research has shown that labeling emotions (also known as “affect labeling”) can help reduce the intensity of negative emotions and improve emotional regulation by engaging the prefrontal cortex in the cognitive processing of emotions.

Thought Process:

“What am I feeling right now? How does my body feel? What thoughts are running through my mind?”

“Which emotion best describes these sensations and thoughts? Am I feeling stressed, sad, frustrated, or something else?”

“Can I refine that feeling into a more specific term, like ‘uneasy’ or ‘disheartened’?”

2. Mindful Interoception and Emotional Awareness

Method: This technique involves cultivating mindfulness to become more aware of internal bodily sensations (interoception), which are closely tied to emotions. Emotions often manifest physically, such as tightness in the chest with anxiety or warmth in the face with embarrassment. By tuning into these sensations, individuals can infer their emotional states.

How it Works: Mindfulness exercises ask individuals to sit quietly and observe the sensations occurring in their bodies without judgment. The focus is not on changing these sensations but on noticing them as they are. This practice heightens awareness of the subtle physiological signals that are often precursors or components of emotions.

Why it Helps: Increased interoceptive awareness can improve emotional recognition because emotions have a strong physiological basis. Many people are disconnected from these bodily signals, but through practice, they can learn to associate physical sensations with emotional states.

Thought Process:

“What physical sensations am I noticing in my body right now? Are my muscles tense, is my breathing shallow, or do I feel warmth or cold?” “What emotion could this bodily sensation be signaling? If I feel tension in my chest, could it be anxiety or anger?” “Can I remain with this sensation and explore it further without trying to suppress or avoid it?”

3. Emotional Schema Mapping

Method: Emotional schema therapy, developed by Robert Leahy, emphasizes understanding the individual’s beliefs and thoughts about emotions rather than the emotions themselves. Emotional schema mapping involves creating a structured framework that links thoughts, beliefs, and emotions to make them easier to identify and process.

How it Works: Individuals are encouraged to explore and write down their automatic thoughts in specific situations, the emotional reactions those thoughts generate, and any deeper beliefs they have about those emotions (e.g., “feeling sad is a weakness”). By deconstructing these schemas, individuals gain insight into their emotional patterns.

Why it Helps: This approach not only helps in recognizing emotions but also allows individuals to challenge unhealthy beliefs they might have about emotions, such as the belief that certain emotions are dangerous or unacceptable. It brings cognitive structure to emotional experiences, making them less ambiguous.

Thought Process:

“What automatic thought did I just have in response to this event? What beliefs might underlie that thought?” “What emotion does this thought or belief bring up in me? Do I feel threatened, ashamed, or hopeful?” “How do I typically respond to this emotion, and is my response helpful or unhelpful?”

4. Cognitive-Behavioral Emotion Tracking (Journaling)

Method: This methodology involves keeping a detailed journal where individuals record their emotions, thoughts, and behaviors throughout the day. The goal is to systematically connect thoughts with feelings and identify patterns over time.

How it Works: Each entry involves documenting:

- The situation or trigger.

- The thoughts that arose in response to that trigger.

- The emotions experienced (with specific attention to emotional intensity).

- The behaviors or actions taken as a result of those emotions.

Why it Helps: Over time, journaling allows for the recognition of emotional patterns and provides individuals with a clearer map of how their thoughts drive their emotions. It externalizes internal processes, making abstract emotions more tangible and analyzable.

Thought Process:

“What happened today that affected my mood?” “What specific thoughts did I have in response to that event? Were these thoughts rational or biased?” “What emotion did I feel in response to those thoughts, and how did I behave afterward?” “Are there patterns I can recognize over time? Do certain types of situations trigger the same emotions?”

5. The ABCDE Model of Emotional Regulation (REBT)

- Method: Rooted in Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), the ABCDE model helps individuals recognize and alter irrational or unhelpful beliefs that give rise to negative emotions.

How it Works:

A stands for the activating event (the external situation). B stands for the belief about that event (the individual’s interpretation). C stands for the consequence (the emotion or behavior that arises from the belief). D involves disputing the irrational belief, challenging its validity. E stands for creating a new, effective belief that leads to healthier emotional consequences.

- Why it Helps: By analyzing how irrational thoughts give rise to negative emotions, individuals can learn to reshape their emotional responses by changing the underlying beliefs. This model encourages a rational thought process to promote healthier emotional regulation.

Thought Process:

“What was the activating event that triggered this emotion?” “What belief or interpretation did I have about the event? Is this belief rational, or could it be distorted?” “What emotional consequence followed? How did I react emotionally?” “Can I dispute this belief? Is there evidence to challenge my interpretation?” “What more balanced belief could I adopt, and how might it affect my emotions?”

6. Emotional Granularity Development

Method: This technique, derived from the work of Lisa Feldman Barrett, involves developing “emotional granularity” — the ability to distinguish between nuanced emotional states, as opposed to merely categorizing emotions as broad states like “happy,” “sad,” or “angry.”

How it Works: Emotional granularity can be developed through exposure to more complex emotional terms and practicing the identification of these emotions in various contexts. For example, instead of just identifying “anger,” one might discern more refined states like “frustration,” “irritation,” or “resentment.”

Why it Helps: High emotional granularity leads to better emotional regulation because individuals who can differentiate between emotions can respond more appropriately to each situation. It fosters a more precise understanding of one’s internal states.

Thought Process:

“Is my emotional state more specific than I initially thought? Can I identify whether I feel stressed, overwhelmed, frustrated, or annoyed?” “What situational context might help clarify my emotion? How do my thoughts about this context shape my specific emotional response?”

Each of these methodologies offers a systematic thought-based approach to recognizing and understanding emotions. They range from labeling emotions and increasing interoceptive awareness to developing emotional granularity and restructuring irrational beliefs. These strategies can be combined and tailored to individual needs, especially for those who struggle with emotional recognition, such as individuals with alexithymia or emotional dysregulation disorders. Over time, these approaches foster improved emotional literacy and a more sophisticated understanding of one’s emotional world.

Let us imagine questions that need be asked in order to recognize contempt? #

To recognize contempt, an emotion that often involves a sense of superiority, disdain, or disrespect toward another person or situation, you would need to ask specific questions that help identify the cognitive, emotional, and physical signs associated with it. Since contempt is a complex emotion with subtle social and psychological cues, the questions would guide an individual to reflect on their thoughts, body language, and reactions toward the target of their contempt.

Here are some questions structured to assist in recognizing contempt:

1. Cognitive/Thought-Process Questions

These questions are designed to explore the thought patterns that might be indicative of contempt, which often involves feelings of moral or intellectual superiority:

- What am I thinking about this person or situation right now?

Contemptuous thoughts often involve judgmental and critical attitudes, such as thinking the other person is “beneath me” or “not worth my time.” Do I believe that I am better, smarter, or more competent than this person?

Contempt frequently arises from a sense of superiority—an inner conviction that the other person is flawed or inferior in some significant way. Am I dismissing or devaluing this person’s opinions, actions, or worth?

Contempt often involves downplaying the other person’s value, leading to dismissal of their contributions or ideas. Do I find myself viewing this person or situation as unworthy of my respect?

Contempt implies a lack of respect, often combined with disdain for the other party’s behavior or views. Am I having sarcastic, cynical, or mocking thoughts about this person?

Sarcasm, mockery, and cynicism are common cognitive expressions of contempt.

2. Emotional Awareness Questions

These questions focus on identifying the emotional underpinnings that accompany contempt. Unlike anger, contempt is often more subtle and feels “cooler” in its expression:

What am I feeling when I think about this person?

Contempt is often a mixture of emotions, including a sense of distaste, arrogance, or smugness, rather than hot anger. Do I feel indifferent or emotionally detached from this person’s well-being?

While anger can involve strong engagement, contempt is often associated with emotional detachment or a “cool” disregard. Do I feel satisfaction or smugness when thinking about this person’s flaws or mistakes?

Contempt can sometimes involve a feeling of self-righteous satisfaction or schadenfreude (pleasure at others’ misfortune). Am I experiencing a sense of disgust or revulsion toward this person’s actions, values, or character?

Disgust is a key component of contempt, especially when the feeling is directed toward what is perceived as moral or personal failure. Am I feeling morally or intellectually superior in this interaction?

Contempt often stems from a feeling of being “above” the other person, morally, intellectually, or socially.

3. Physical/Bodily Awareness Questions

Recognizing the physical manifestations of contempt can provide crucial clues, particularly because contempt often shows up in nonverbal behavior before it is consciously recognized. These questions help identify body language and physiological cues:

Is my facial expression showing signs of a sneer or a curled lip?

Contempt is frequently expressed through nonverbal cues, such as a sneer, where one side of the mouth lifts slightly, or a narrowing of the eyes. Am I rolling my eyes, sighing, or displaying other dismissive body language?

Eye-rolling and sighing are common signs of contempt in interpersonal interactions, signaling frustration and disdain. Do I feel a sense of physical distance or disengagement in my body posture?

Contempt is often associated with a lack of physical warmth, such as turning away from the person or crossing arms in a defensive manner. Do I feel tension in my facial muscles, particularly around my mouth or eyes, when interacting with this person?

Physical tension in the face, particularly around the mouth (sneer) or a tightening of the eyes, can signal contempt. Am I avoiding eye contact or giving someone a dismissive look?

Withholding eye contact or offering a dismissive glance can be an unconscious manifestation of contempt.

4. Behavioral Questions

These questions help in identifying behavioral cues that reflect a contemptuous attitude in interactions:

Am I speaking in a sarcastic or mocking tone of voice?

Contempt often leaks into vocal tone through sarcasm, condescension, or dismissive phrasing. Do I find myself engaging in subtle put-downs or veiled insults toward this person?

People who feel contempt may deliver insults or criticisms in a passive-aggressive manner, often masking them as jokes or “honest feedback.” Am I avoiding constructive engagement with this person and instead opting for criticism?

Contempt can manifest in a refusal to engage meaningfully, often focusing on highlighting the other person’s flaws rather than offering solutions. Do I dismiss their ideas or contributions without genuinely considering them?

Contempt involves quick dismissal of the other person’s input, usually based on the belief that their opinions lack value. Am I showing impatience, frustration, or condescension in my body language or speech?

People experiencing contempt may show clear signs of impatience, condescension, or frustration, particularly in the way they engage (or avoid engagement) with the person.

5. Social/Contextual Awareness Questions

Contempt is often influenced by social dynamics, so it is important to ask questions that help situate the emotion within a broader context:

Is there a power dynamic at play where I feel I have an advantage over this person?

Contempt can often emerge in situations where one party feels more powerful, competent, or morally superior to the other. Do I feel that this person has violated a core value or moral principle I hold?

Moral superiority is a key feature of contempt, which often arises when someone believes the other person has crossed an ethical boundary. Am I placing myself on a pedestal, viewing this person as morally or intellectually inferior?

Contempt often involves comparing oneself favorably to the other person, seeing them as unworthy or deficient in some key aspect. Is there a pattern in my relationships where I tend to feel superior or condescending toward others in similar situations?

Recognizing patterns in one’s social dynamics can help identify if contempt is a recurring emotion, particularly in competitive or hierarchical situations.

6. Reflective Questions

These questions encourage deeper reflection on how contempt impacts personal relationships and broader social interactions:

How might my contemptuous attitude affect my relationship with this person?

Contempt is one of the most toxic emotions in interpersonal relationships, and reflecting on its consequences may help modify behavior. Am I contributing to a breakdown in communication by holding this contemptuous attitude?

Contempt tends to shut down healthy communication, often leading to further misunderstandings and conflict. Is my contempt based on assumptions or judgments about this person, or do I have valid reasons to feel this way?

Distinguishing between justified criticism and unhealthy contempt is crucial for maintaining fairness in relationships. Can I find a way to reframe this situation to reduce my feelings of contempt?

Reframing the situation may help reduce contempt by encouraging empathy and understanding.

Recognizing contempt involves careful reflection on cognitive patterns, emotional signals, physical cues, and behavioral tendencies. By asking targeted questions in these areas, individuals can identify when they are feeling contempt, understand the origins of the emotion, and consider its effects on their interpersonal relationships. The ability to identify and mitigate contempt is crucial, as it is a corrosive emotion that can erode trust and respect in personal and professional interactions.

Let us attempt the same for love? #

To recognize love, a deeply complex and multifaceted emotion, one must explore both its internal and external manifestations. Love can take many forms—romantic, platonic, familial, or self-love—and the emotions, thoughts, and behaviors it generates can vary widely depending on the context. Below, we will structure questions aimed at helping an individual identify and understand the presence of love in its many dimensions. These questions will cover cognitive, emotional, physical, behavioral, and social elements, guiding one through the thought processes that reveal the presence of love.

1. Cognitive/Thought-Process Questions

These questions help explore the cognitive and mental aspects of love, which often involves positive, affirming, and empathetic thoughts toward another person or oneself:

Do I frequently think about this person and their well-being?

Love often manifests as an ongoing concern for another person’s happiness and welfare, whether in a romantic, familial, or platonic context. Do I see the best in this person, even when they have flaws or make mistakes?

Love tends to foster understanding, forgiveness, and acceptance of imperfections, seeing beyond surface-level faults. Do I feel a desire to support and encourage this person’s growth and happiness?

In love, there is often a strong drive to see the other person thrive, with genuine interest in their personal development. Do I feel a sense of connection or shared purpose with this person?

Love often brings a feeling of being united with another person, sharing common goals, values, or a sense of purpose in life. Am I willing to compromise or sacrifice my own comfort to see this person happy or fulfilled?

Love frequently involves selflessness, a readiness to prioritize the other person’s needs without feeling resentment.

2. Emotional Awareness Questions

These questions focus on identifying the emotional responses associated with love, which are typically positive, but can also include complex, protective, and nurturing feelings:

Do I feel warmth, tenderness, or affection when I think about this person?

Love is often accompanied by a warm, gentle feeling toward the other person, which may manifest as tenderness or deep affection. Do I feel calm and content when I am around this person?

Love often brings a sense of emotional stability and peace, even in the presence of difficulties or challenges. Do I feel joy or happiness when I see this person happy or fulfilled?

A strong indicator of love is the ability to derive happiness from the joy of the other, experiencing what is known as empathic joy. Do I feel protective or concerned when this person is in distress?

Love often includes protective instincts, where one feels a deep concern for the other person’s safety, emotional state, or well-being. Do I experience a deep sense of connection or belonging when with this person?

Love fosters a profound sense of emotional connection, where one feels “at home” with the other person, regardless of circumstances.

3. Physical/Bodily Awareness Questions

Love also manifests in physical sensations and body language, often through comfort, warmth, and a desire for closeness:

Do I feel drawn to physical closeness with this person (e.g., touch, hugs, holding hands)?

Physical affection, such as hugging, holding hands, or even a desire to be near the other person, is often a key physical indicator of love. Do I feel a sense of calm and relaxation in their presence?

Being in the presence of someone you love often generates a sense of ease and relaxation, as your body responds to feelings of safety and emotional closeness. Do I feel energized or uplifted when I am with this person?

Love can have invigorating physical effects, making one feel more energized, uplifted, or “lighter” when around the loved one. Is my body language open and inviting when I am near this person?

Open body language—such as facing the person, making eye contact, and unconsciously leaning toward them—can be signs of love’s presence. Do I feel a comforting sense of warmth or contentment when I hold or touch this person?

Physical touch in the context of love often leads to feelings of comfort, warmth, and emotional connection.

4. Behavioral Questions

Love influences behavior in both subtle and obvious ways. These questions explore how one’s actions reflect love:

Do I often go out of my way to do things for this person, even without being asked?

Acts of service or kindness are common behavioral expressions of love, where one takes initiative to care for or support the loved one. Do I show appreciation and gratitude toward this person for who they are?

Love often manifests in expressions of gratitude and appreciation, where one regularly acknowledges the value and importance of the other person. Am I patient and understanding when this person is going through difficult times?

Patience and emotional support during tough situations are key behaviors that indicate the presence of love. Do I find joy in doing small, thoughtful things for this person without expecting anything in return?

In love, small gestures—like preparing a favorite meal, offering emotional support, or doing something unexpected—often come naturally. Do I actively listen and empathize with this person’s thoughts and feelings, even if I don’t fully understand or agree with them?

Love motivates people to listen deeply and seek to understand the other person, demonstrating care through active engagement and empathy.

5. Social/Contextual Awareness Questions

Love often exists in a social context, with roles and dynamics that shape how it manifests. These questions help recognize love in specific relational contexts:

Do I enjoy sharing important moments and experiences with this person?

Love is often revealed through the desire to share life’s meaningful experiences—whether successes, challenges, or everyday moments. Do I feel a deep sense of trust and mutual respect in our relationship?

Love is closely tied to trust and respect, where both parties feel safe to be vulnerable and rely on each other. Do I feel that this relationship enhances my life and helps me grow as a person?

In loving relationships, there is often a feeling of personal growth, with the relationship enriching one’s emotional and psychological development. Do I prioritize this person in my social life and feel fulfilled by our connection?

Love naturally leads to prioritizing the other person in one’s social circle, often making time and space for them to play an essential role in life. Am I willing to weather difficult times with this person because I believe in the strength of our bond?

Love strengthens one’s commitment to stand by the other person through challenging times, seeing difficulties as opportunities to strengthen the relationship.

6. Reflective Questions

These questions encourage deeper reflection on the nature of love, exploring its long-term effects and broader significance:

Does being with this person make me feel like a better version of myself?

Love often inspires personal growth, where being with the loved one enhances one’s sense of self and fosters positive change. Do I feel a sense of unconditional regard for this person, regardless of circumstances?

Love, especially deep love, is often unconditional, with one’s affection not being contingent on external circumstances or temporary setbacks. Can I imagine my life without this person, and if so, how would I feel?

Imagining life without the loved one often reveals the depth of emotional connection, with love making the thought of separation feel painful or incomplete. Do I feel secure and confident in the long-term strength of our bond?

Love fosters a sense of security and stability, where the future feels more certain because of the presence of the other person. Am I willing to forgive and move forward after conflicts or disagreements because of my love for this person?

Love includes forgiveness and the capacity to resolve conflicts, valuing the relationship over the temporary disruptions that may arise.

Recognizing love involves a holistic approach that examines thought patterns, emotional experiences, physical cues, behavioral actions, and social dynamics. The questions outlined above help uncover various facets of love, ranging from affection and care to deeper emotional commitments and behavioral expressions. By thoughtfully considering these questions, individuals can better understand when and how love is present in their relationships, and how it influences their inner world and external interactions.

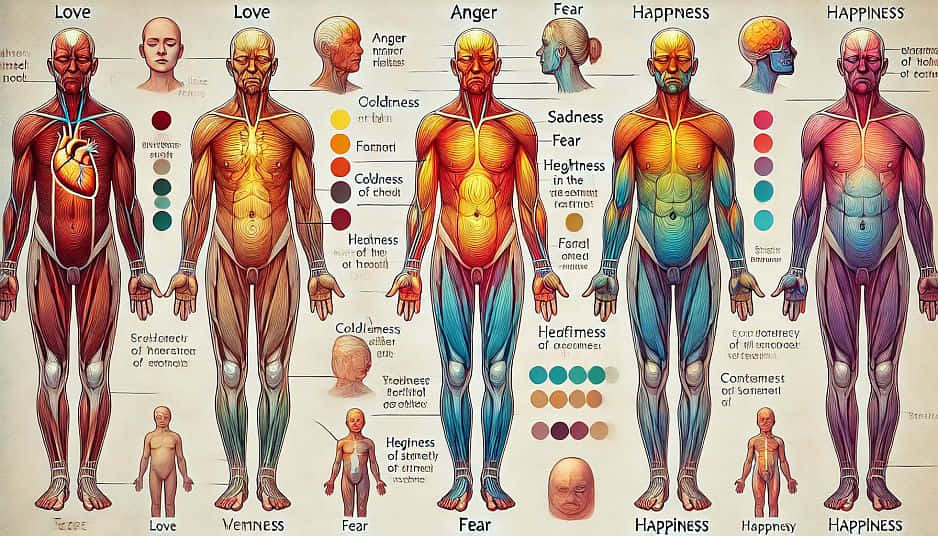

Please create a table of main emotions and indicate parts of the body where the feeling can be expected? #

Here is a table outlining the main emotions and the corresponding parts of the body where these feelings are typically experienced:

| Emotion | Body Areas Typically Affected |

|---|---|

| Love | Warmth or openness in the chest (heart area), lightness in the chest, relaxation in the body. |

| Anger | Tension in the jaw, fists, and neck; heat in the face and hands; general muscle tightness. |

| Fear | Tightness or cold sensation in the stomach, rapid heartbeat, trembling in the limbs, dry mouth. |

| Sadness | Heaviness in the chest, lump in the throat, slow breathing, tears forming in the eyes. |

| Happiness | Lightness or energy throughout the body, especially in the chest and face; relaxed muscles. |

| Contempt | Tightening or discomfort around the mouth, sneer on one side of the face, tension in the eyes. |

| Surprise | Sudden widening of the eyes, raised eyebrows, quick intake of breath, increased heart rate. |

| Disgust | Nausea or queasiness in the stomach, wrinkling of the nose, throat tightness, desire to withdraw. |

| Embarrassment | Warmth or flushing in the face, slight sweating, discomfort in the stomach, averting gaze. |

This table highlights the most common physical sensations associated with these emotions, though individual experiences may vary. The body often reflects our emotional state through subtle (or strong) physiological reactions.

Please describe four dimensions of alexithymia (DIF, DDF etc.)? #

Alexithymia is commonly described along four key dimensions, each reflecting a different aspect of emotional processing difficulties. These dimensions are often assessed using psychometric tools like the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20), and they represent the specific challenges that individuals with alexithymia face. The four dimensions are:

- Difficulty Identifying Feelings (DIF)

- Description: This dimension refers to the inability to accurately recognize and identify one’s emotional states. Individuals with high DIF may struggle to distinguish between different emotions or may not be able to tell when they are feeling emotions at all.

Key Features:

Confusion about emotional experiences.

Inability to differentiate between emotions and physical sensations (e.g., mistaking anxiety for a stomach ache).

Often results in the misinterpretation of one’s internal states.

Example: A person might feel physical tension but be unable to recognize that the tension is linked to anxiety or frustration.

- Difficulty Describing Feelings (DDF)

- Description: DDF relates to the inability to verbalize or articulate emotions to others. Even when someone with alexithymia can somewhat identify their feelings, they may find it hard to put those emotions into words.

Key Features:

- Poor emotional vocabulary.

- Difficulty in expressing or communicating emotional experiences.

- Frustration when asked to explain how one is feeling.

Example: A person may say, “I feel bad,” but struggle to elaborate on whether that means they are sad, angry, or anxious.

- Externally Oriented Thinking (EOT)

- Description: This dimension reflects a focus on the external, concrete world over internal emotional experiences. Individuals with high EOT tend to think in a practical, detail-oriented manner, often avoiding introspection or emotional reflection.

Key Features:

Focus on external tasks and objects rather than personal feelings or internal states.

Tendency to downplay the importance of emotions in daily life.

Preference for logical or factual discussions over emotional or introspective topics.

Example: A person might discuss the facts of a situation (e.g., what happened during a conflict) without considering or reflecting on how they or others felt during the event.

- Restricted Imaginal Processes (often discussed but not part of TAS-20)

- Description: While not part of the standard TAS-20 scale, restricted imaginal processes are often discussed as an important feature of alexithymia. It involves a limited capacity for imagination, fantasy, and creativity, which correlates with a diminished ability to engage with emotions and daydreaming.

Key Features:

Lack of daydreaming or imaginative thinking.

Difficulty engaging in creative or abstract thoughts related to emotions.

Limited or absent use of fantasy as a form of emotional exploration.

Example: A person might rarely engage in fantasies or imaginative activities, focusing instead on concrete, real-world tasks and problems.

In sum, the four key dimensions (DIF, DDF, EOT, and, in some cases, restricted imaginal processes) together form the core profile of alexithymia. Each dimension highlights a different aspect of emotional processing deficits, from recognizing emotions to expressing them, reflecting on them, or engaging in emotional imagination.

Is there an online Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) test? #

Yes, there are several websites where you can take the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) test online. This is a standardized 20-item self-report questionnaire used to measure alexithymia, including subscales for difficulty identifying feelings (DIF), difficulty describing feelings (DDF), and externally oriented thinking (EOT). The TAS-20 test can provide insights into your emotional processing abilities.

For example, you can take the test on Embrace Autism, which offers a structured online format for the TAS-20. After completing the test, you’ll receive a score that indicates where you fall on the alexithymia spectrum, and a breakdown of your performance across its subscales. This can be useful for understanding how alexithymia affects different areas of your emotional life.

Additionally, Psycho-Tests and Autistic Hub offer similar online versions of the TAS-20, providing a quick way to assess whether alexithymia might be a relevant issue for you.

These online tests are free and provide immediate feedback, though they are for educational purposes only and not a substitute for professional diagnosis.