A versatile metaphor for the nature of truth, enlightenment, and social dynamics.

A versatile metaphor for the nature of truth, enlightenment, and social dynamics.

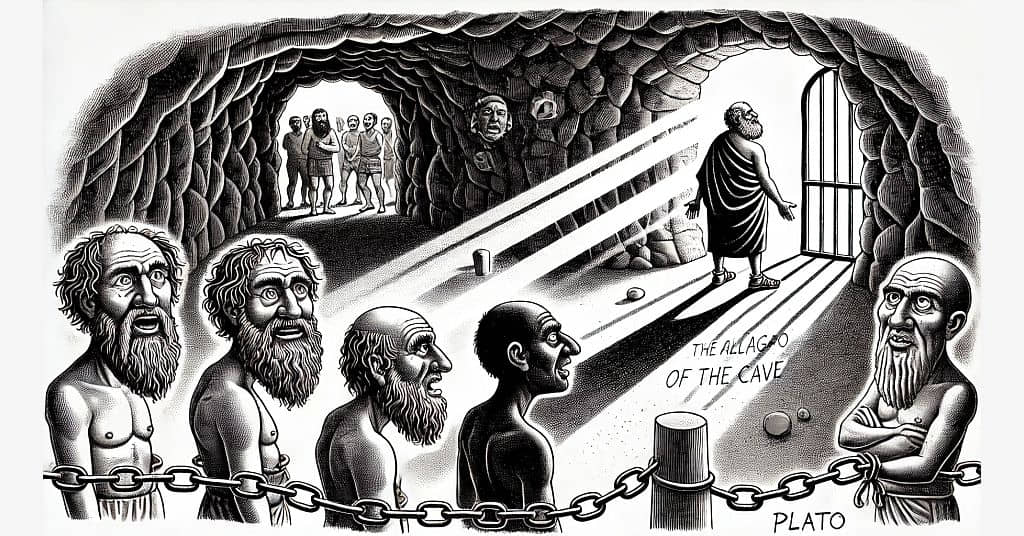

Allegory of the Cave #

Plato was quoted as saying: “Those who are able to see beyond the shadows and lies of their culture will never be understood, let alone believed, by the masses”. Our question is: are knowledge, autonomy and intelligence all gates to loneliness? #

This question resonates with a longstanding philosophical theme concerning the individual’s relationship to knowledge and society. Plato’s quote addresses a profound isolation that arises from seeing beyond the “shadows and lies” — a clear allusion to his Allegory of the Cave, where enlightenment enables the philosopher to see the world as it is, not as mere shadows on a wall. This capacity to discern the “truth” fundamentally alienates the individual from those still immersed in illusion. Knowledge, autonomy, and intelligence, when they lead to such clarity, may indeed create a form of existential loneliness. However, whether they always do so is worth analyzing.

Knowledge as a Source of Isolation

Knowledge elevates one’s understanding, expanding horizons but also often revealing uncomfortable truths. As one’s knowledge deepens, it can create a chasm between oneself and others who may not share the same worldview or understanding. Knowledge, especially of a profound or philosophical nature, can be difficult to convey meaningfully, especially when it challenges widely held beliefs or disrupts the comfort of shared illusions. This gulf is not simply intellectual but emotional and social, as new perspectives can dislocate the individual from shared societal norms. Yet, this isolation is not inevitable; knowledge, when it finds others similarly attuned, can also be the basis for profound intellectual and emotional connection.

Autonomy and the Challenge of Self-Determination

Autonomy, the capacity for self-determined action, often results in an individual diverging from collective norms. Autonomous people define their actions and values independently, sometimes at odds with societal conventions, leading to isolation when society views such divergence as alien or threatening. Autonomy implies a rejection of dogma, which, for some, is a solitary path by necessity. However, autonomy can also manifest in ways that attract others who value independence, thereby fostering community among like-minded individuals. Therefore, autonomy may isolate, but it can also magnetize, creating shared spaces of free thought and collaboration.

Intelligence and the Burden of Perception

Intelligence, especially in forms that foster critical thinking and innovation, can be isolating because it allows individuals to perceive complexities, contradictions, and nuances that others may overlook. High intelligence can enable a person to connect disparate ideas, notice patterns, or critique systems in ways that might seem incomprehensible to those around them. Intelligent individuals may struggle to relate to those who view the world in simpler terms, not out of superiority, but out of sheer difference in perspective. Still, like knowledge, intelligence can also forge bonds when shared; it may be rare, but communities of intellectual equals do exist, often providing respite from loneliness.

Loneliness as an Existential Byproduct

The convergence of knowledge, autonomy, and intelligence can indeed create loneliness as an existential state. With heightened perception, one may struggle to reconcile personal understanding with societal norms, leading to what existentialists like Kierkegaard might describe as a “teleological suspension of the ethical,” where one transcends societal codes for personal truths. Nietzsche echoes this in his concept of the “Übermensch,” a figure who must bear isolation in the pursuit of individual authenticity. Yet, loneliness in this sense is not necessarily undesirable; it can be a crucible for self-realization, leading individuals to deeper insight into themselves and the nature of human existence.

Are These Qualities Always Gates to Loneliness?

While these qualities often accompany a degree of isolation, loneliness is not inevitable. The internet, globalized communication, and intellectual communities have created unprecedented access to like-minded individuals. The alienation that Plato feared may not be as absolute in today’s world, where those who “see beyond” can seek out others who share their vision. Philosophical circles, intellectual forums, and creative collaborations have grown in response to this need, allowing individuals to overcome isolation through shared understanding. The modern world thus provides ways to transcend this loneliness, even as these traits remain potentially isolating.

Conclusion: An Ambiguous Relationship

In sum, knowledge, autonomy, and intelligence are not inherently gates to loneliness but are often paths that demand courage to traverse, for they frequently lead individuals into realms where they may be misunderstood. For some, this solitude is empowering, a space for self-reflection and authentic expression. For others, it can be a source of anguish. Ultimately, loneliness in this context may be more a reflection of societal structures than an intrinsic feature of these qualities; in a world where truth, autonomy, and intelligence are more widely valued, perhaps the philosopher’s loneliness would be far less acute.

Let us rehash Allegory of the Cave and mention subsequent philosophical interpretations? #

The Allegory of the Cave, presented in Book VII of The Republic, remains one of Plato’s most compelling explorations of human perception, knowledge, and enlightenment. In the allegory, prisoners are chained inside a cave, forced to face a wall, on which they see shadows cast by objects behind them, illuminated by a fire. For the prisoners, these shadows constitute their entire reality. One prisoner, however, escapes, venturing out of the cave to witness the world as it truly is, illuminated by the sun. This newfound clarity represents enlightenment, where truth, rather than shadow, forms the basis of understanding.

Upon returning to the cave to share his discovery, the enlightened prisoner is met with hostility and disbelief. The other prisoners, still convinced of the veracity of their shadowed existence, resist this “truth,” preferring the familiarity of their illusions. This allegory encapsulates Plato’s theory of Forms, where the sun represents the ultimate truth, the “Form of the Good,” and the cave embodies the deceptive world of appearances that traps human beings in ignorance.

Classical Interpretations: Epistemology and the Theory of Forms

In classical philosophy, the Allegory of the Cave primarily illustrates Plato’s epistemology and his Theory of Forms. For Plato, the shadows on the wall represent the empirical world we perceive through our senses—an imperfect, mutable, and deceptive reality. True knowledge, in Plato’s view, is not gained through the senses but through rational insight into the unchanging Forms, which are the real, ideal essences of things. For instance, a physical chair represents an imperfect copy of the ideal Form of “Chairness.” Thus, the journey out of the cave symbolizes the philosopher’s ascent from ignorance to knowledge, from sensory perception to intellectual understanding.

The Allegory also has a political dimension; it advocates for the philosopher-king, the one who has seen the truth (left the cave) and therefore possesses the wisdom to rule. However, as the allegory shows, those who remain unenlightened often reject or even resist the philosopher’s insights, suggesting that leadership based on wisdom may always face opposition from the unknowing majority.

Medieval Christian Interpretations: The Ascent to God

Medieval Christian philosophers, especially St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, interpreted the allegory in a religious light, seeing the cave as a metaphor for the soul’s separation from God. For Augustine, the journey out of the cave was analogous to the soul’s ascent toward divine illumination, whereby knowledge is reached not through worldly pursuits but through a turn inward and upward, toward God as the ultimate truth. Aquinas, who synthesized Aristotelian and Platonic thought within Christian theology, viewed the cave as a metaphor for human ignorance and sin, with divine enlightenment providing the means to escape.

Enlightenment and Romantic Interpretations: Autonomy and Inner Experience

In the Enlightenment, thinkers like Immanuel Kant reinterpreted the allegory to emphasize autonomy and intellectual freedom. For Kant, the allegory symbolized humanity’s need to move beyond “self-incurred immaturity,” challenging the influence of dogmatic authorities (akin to the shadows on the wall). In his essay What is Enlightenment?, Kant argued that enlightenment is the ability to use one’s understanding without guidance, a process that requires courage and is, in a sense, a journey out of the cave.

The Romantics, on the other hand, embraced the allegory as a commentary on the depth of inner experience. Friedrich Schelling and others saw the external world as secondary to the internal, as the allegory suggests that reality is not a simple, objective truth but something that can be apprehended deeply within. The Romantics thus highlighted the subjective experience of enlightenment, wherein the journey out of the cave is an individualistic search for truth rather than a universal ascent to knowledge.

Nietzschean Interpretation: Power, Perspectivism, and Truth

Friedrich Nietzsche offered a provocative critique of Plato’s allegory. He challenged the notion of an absolute truth (symbolized by the sun), arguing instead for perspectivism: the view that truth is a matter of perspective rather than a universal ideal. Nietzsche saw the allegory as reinforcing a problematic dichotomy between the material world (the cave) and an idealized realm of truth (outside the cave). By emphasizing perspectivism, Nietzsche suggested that what we call “truth” is inherently linked to human interests, power, and will, casting doubt on the notion of an ultimate, singular enlightenment. In Nietzsche’s view, the philosopher is not simply one who sees “the truth” but one who creates meaning and asserts values, challenging the Platonic ideal of objective knowledge.

Heideggerian Analysis: Being and Authenticity

Martin Heidegger revisited the allegory in his exploration of Being and authenticity. He viewed the cave as a metaphor for human existence in the world, emphasizing the experience of being-in-the-world (Dasein). For Heidegger, the escape from the cave represented a movement toward authenticity, where one confronts the nature of Being itself rather than accepting socially imposed structures and definitions. Heidegger questioned the notion of enlightenment as simply gaining “knowledge,” instead viewing it as a fundamental shift in one’s orientation toward existence. For him, the journey out of the cave was a shift from superficial, inauthentic ways of being to an authentic engagement with reality.

Critical Theory: Ideology and Cultural Hegemony

The Allegory of the Cave also finds resonance in Critical Theory, especially in the works of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer. In their analysis of ideology and cultural hegemony, the cave symbolizes the ways in which ideology constrains perception, with the shadows on the wall representing the manipulative images propagated by culture and media. Escaping the cave, in this sense, involves a critical examination of the systems of power that shape our beliefs, from capitalism to mass media. For Adorno, true enlightenment requires an awareness of how cultural “shadows” distort our understanding, much like Plato’s prisoners accepting illusions as reality.

Simone de Beauvoir and Existentialist Feminism: Transcendence and Immanence

In existentialist feminism, Simone de Beauvoir adapted elements of the allegory to describe the condition of women in a patriarchal society. The cave symbolizes the realm of immanence, where women, traditionally confined to domesticity and social limitations, are kept in metaphorical chains. True freedom, or transcendence, is achieved by moving beyond the limitations imposed by society, akin to the philosopher escaping the cave. For de Beauvoir, the existential project is to create one’s own meaning, challenging societal restrictions and embracing individual freedom in the face of existential ambiguity.

Contemporary Readings: Postmodernism and the Rejection of Absolute Truth

In postmodern interpretations, the Allegory of the Cave has been re-envisioned as a commentary on the instability of truth and knowledge itself. Michel Foucault and Jean Baudrillard reject the dichotomy between reality and illusion that Plato proposes. Foucault, for example, argues that knowledge is inextricable from power, making the notion of an ultimate, objective truth a construct of authority. Baudrillard extends this by positing the idea of “hyperreality,” where simulations of reality (e.g., media, technology) replace any original truth, making it impossible to know whether one is inside or outside the cave. In this reading, Plato’s shadows have become reality itself, and the idea of escape is an illusion.

Conclusion: A Philosophical Kaleidoscope

The Allegory of the Cave has undergone a transformation across centuries, serving as a versatile metaphor for the nature of truth, enlightenment, and social dynamics. Each philosophical tradition finds in it a unique expression of its own insights, whether focused on the objective existence of truth, the nature of power, or the limits of human perception. In this sense, Plato’s cave remains an intellectual landscape, continuously reshaped by the questions and concerns of each era, reminding us that truth, like the sunlight outside the cave, is forever sought but perhaps never fully attained.

| Philosophical Tradition | Key Thinker(s) | Interpretation of the Allegory | Key Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical (Epistemology & Theory of Forms) | Plato | The cave represents ignorance; shadows symbolize sensory illusions. Enlightenment is the ascent to true knowledge of the unchanging Forms, especially the Form of the Good. | Knowledge, Forms, philosopher-king |

| Medieval Christian | Augustine, Aquinas | The cave symbolizes the soul’s separation from God; enlightenment is the soul’s ascent towards divine truth. | Divine illumination, ascent to God |

| Enlightenment | Immanuel Kant | The allegory reflects humanity’s move beyond dogmatic authority toward intellectual freedom and self-determination. | Autonomy, freedom from dogma |

| Romanticism | Friedrich Schelling | Inner experience is primary; enlightenment is an individual, subjective journey to discover personal truth rather than a universal one. | Inner experience, subjectivity |

| Nietzschean (Perspectivism) | Friedrich Nietzsche | Challenges the existence of an absolute truth; “truth” is subjective and tied to human interests, will, and perspective. | Perspectivism, will to power, critique of truth |

| Heideggerian (Existential Authenticity) | Martin Heidegger | The cave represents inauthentic existence; enlightenment is a shift toward authenticity, engaging with the true nature of Being. | Authenticity, being-in-the-world |

| Critical Theory (Ideology & Hegemony) | Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer | The cave symbolizes ideological constraints; enlightenment requires critical awareness of power structures that distort perception (e.g., media, capitalism). | Ideology, cultural hegemony, critique of media |

| Existential Feminism | Simone de Beauvoir | The cave reflects the confinement of women in patriarchal roles; transcendence is achieved by moving beyond social limitations. | Immanence vs. transcendence, individual freedom |

| Postmodernism (Hyperreality) | Michel Foucault, Jean Baudrillard | Challenges the concept of objective truth; reality and illusion blur, and it becomes unclear if escape from the “cave” is possible. | Hyperreality, power-knowledge, critique of truth |