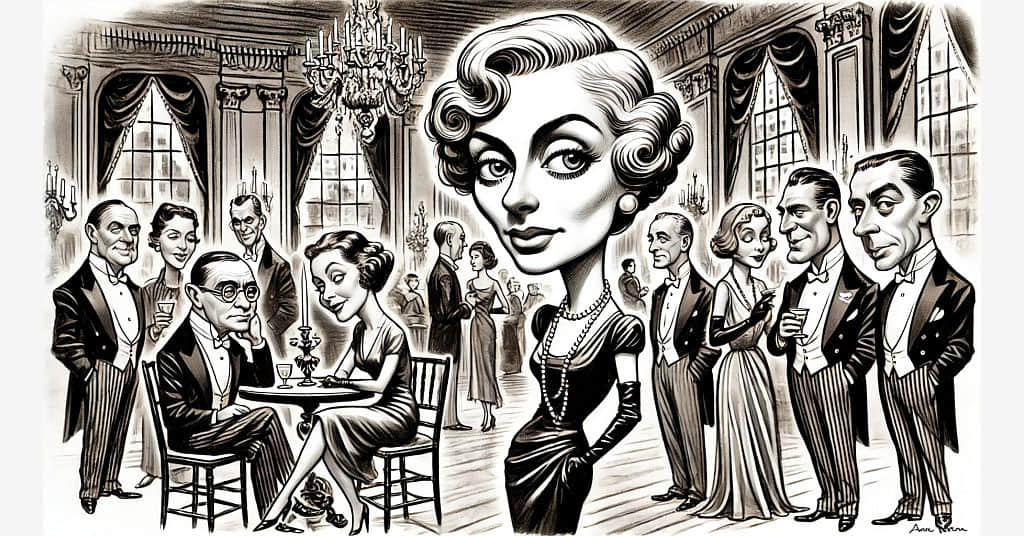

The contradictions within her inner world were the very source of her creative energy.

The contradictions within her inner world were the very source of her creative energy.

Anaïs Nin #

How did Anaïs Nin die? #

Anaïs Nin, the acclaimed French-Cuban-American diarist and writer, passed away on January 14, 1977, in Los Angeles, California, at the age of 73. She died from complications related to cervical cancer, which she had been battling for several years. Nin was diagnosed with cancer in the early 1970s and underwent various treatments, including radiation therapy, but the disease eventually became terminal.

Her death marked the end of a life that had been deeply immersed in literature, psychoanalysis, and personal introspection. Nin’s legacy, particularly her candid and introspective diaries, continues to have a significant impact on feminist literature and autobiographical writing.

Tell me about her childhood and parents? #

Anaïs Nin was born on February 21, 1903, in Neuilly-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris, France, to a Cuban father, Joaquín Nin, and a Danish-French mother, Rosa Culmell. Her parents’ lives and personalities played a significant role in shaping her childhood and her future as a writer.

Joaquín Nin (Father):

Joaquín Nin was a Cuban composer and pianist, known for his artistic temperament and charisma. Coming from a cultured family, Joaquín was ambitious and devoted to his musical career, but also prone to being emotionally erratic and self-centered. His passion for music and his romantic entanglements deeply affected Anaïs. When she was around 11 years old, her father abandoned the family, leaving a lasting wound that shaped her life and writing. Anaïs’s complicated relationship with her father is explored throughout her diaries, where she writes about her mixed feelings of longing and resentment, as well as her attempts to understand his influence on her own identity.

Rosa Culmell (Mother):

Rosa Culmell came from a conservative, affluent Danish and French-Cuban family, with ties to both art and high society. She had been a classically trained singer but sacrificed much of her musical aspirations to support her husband and children. After Joaquín left the family, Rosa became the stabilizing force in Anaïs’s life, moving with her children from Europe to the United States. She was strict, protective, and deeply religious, raising Anaïs in a disciplined and Catholic environment. This relationship with her mother also had its complexities; Rosa’s somewhat rigid approach to life conflicted with Anaïs’s burgeoning artistic and sensual curiosity, though she provided financial and emotional support during difficult times.

Childhood:

Nin’s early years were shaped by this tension between her artistic parents and their eventual separation. The family’s financial instability and her father’s abandonment led them to move frequently. After Joaquín left, Rosa took Anaïs and her two brothers to New York City in 1914. The experience of displacement—leaving her familiar European surroundings for a new and often harsh life in America—became a formative theme in Anaïs’s diaries. As a young girl, she wrote prolifically, beginning her famous diary at the age of 11 as a form of therapy and a way to communicate her feelings about her father’s departure.

While living in the U.S., Anaïs struggled to fit in, navigating a new language and culture. Her adolescent years were marked by a sense of alienation, but her inner life flourished through her writing. The diary, which would become a hallmark of her literary work, initially began as a letter to her absent father, reflecting her desire to reconcile with him and understand his actions.

Influence of Her Parents:

Both parents played pivotal roles in Nin’s psychological and creative development. Her father’s abandonment led to deep emotional scars, which she would later explore in her writing, especially in the context of eroticism, psychoanalysis, and identity. The complexity of her relationships with both parents drove her intense need for self-exploration, self-expression, and her lifelong interest in psychology (she became a student of psychoanalysis) and art.

Anaïs’s tumultuous childhood, marked by emotional instability, exile, and longing, became the groundwork for her future literary work. Her diaries, which spanned over several decades, were often ways for her to process the unresolved emotional conflicts stemming from her early life, especially concerning her relationships with both parents.

What about Nin’s relationships? #

Anaïs Nin’s relationships were as complex and unconventional as her writing. Throughout her life, she was involved in a series of intense, often overlapping romantic, intellectual, and artistic relationships that reflected her desire for emotional and creative fulfillment. Her most significant relationships were often deeply intertwined with her artistic development, psychoanalytic explorations, and personal philosophy of rejecting conventional societal norms regarding love and marriage.

Here is an overview of the most prominent relationships in her life:

Hugh Parker Guiler (Husband):

Anaïs Nin married Hugh Parker Guiler, a banker and artist, in 1923. Known as Ian Hugo in the art world (he became an experimental filmmaker), Guiler remained a constant presence in Nin’s life until her death. Their marriage was unconventional, especially in its later years. While Guiler provided financial stability, and the two shared a companionship, their relationship became increasingly distant over time, particularly as Nin pursued other lovers. Guiler knew about her diaries but was unaware of the full extent of her extramarital affairs, though he did permit her the freedom to pursue her creative interests and maintain her various relationships. Nin often compartmentalized her relationship with Guiler from her other more passionate and intense liaisons.

Henry Miller:

One of Nin’s most famous and significant relationships was with American writer Henry Miller, whom she met in Paris in 1931. Their passionate affair began when Miller was still married to June Miller, a woman who also fascinated Nin. Their intense intellectual connection, as well as their shared love for artistic experimentation, made Miller one of the most important figures in Nin’s life. She helped support Miller financially and encouraged his writing career, even going as far as to use her resources to print his work when publishers were hesitant.

Their love affair was driven by a mutual fascination with each other’s talents and personalities. Miller respected Nin as a writer and considered her diaries some of the finest prose he had ever read. For Nin, Miller became a symbol of the type of creative and sexual freedom she craved. Their affair was deeply erotic and is famously chronicled in both their letters and in Nin’s diaries. It was a formative period for Nin’s sexual awakening and artistic identity. Despite the intense passion, their relationship eventually transformed into a deep friendship, though it remained emotionally complex.

Gonzalo Moré:

Nin also had a significant relationship with Gonzalo Moré, a Peruvian bohemian whom she met in Paris. Their relationship began in the 1930s, when she was still involved with Henry Miller. Moré was another figure who inspired Nin’s creative imagination, though their relationship became strained by his personal issues and lack of stability. Nin helped support him and his wife, Helba Huara, a dancer, for several years, despite the complications their involvement created. Like many of her relationships, this affair was deeply romantic but ultimately unfulfilled in terms of practical realities.

Otto Rank:

Psychoanalysis had a profound impact on Nin’s personal and literary development, and one of her most important relationships was with Otto Rank, a prominent psychoanalyst and former student of Sigmund Freud. Nin entered therapy with Rank in 1932, seeking to understand her own psyche and inner turmoil. Their professional relationship soon evolved into a personal and romantic affair.

Rank’s influence on Nin was profound; he encouraged her to embrace her creative impulses and write from her deepest, most authentic emotions. He became both a mentor and a lover, helping her refine her literary voice and approach to psychoanalysis. Rank’s belief in the healing power of artistic expression resonated with Nin, who eventually integrated many psychoanalytic themes into her work. Their relationship ended after Rank moved to the United States, but his impact on her remained a key aspect of her life and writing.

Rupert Pole:

In 1947, while still married to Hugh Guiler, Nin met Rupert Pole, a younger actor, and their relationship blossomed into a passionate love affair. In the 1950s, she began living a double life, effectively marrying Pole in 1955 while still legally married to Guiler. She lived alternately with each man in different parts of the country: she spent time with Guiler in New York and then with Pole in California, without either being fully aware of the other for many years. Nin’s bi-coastal lifestyle allowed her to compartmentalize her relationships, maintaining her dual marriages for nearly 20 years.

With Pole, Nin found a different kind of fulfillment, both emotionally and spiritually. He provided her with the unconditional love and attention she craved, but their relationship also revealed the complexities of Nin’s desire for independence versus intimacy. Pole remained devoted to Nin until her death, and after her passing, he played a critical role in editing and publishing her unexpurgated diaries.

June Miller:

Although primarily a romantic and sexual figure in Henry Miller’s life, June Miller was a significant figure for Anaïs Nin as well. Anaïs was fascinated by June’s beauty, mystique, and emotional intensity. At times, her attraction to June bordered on obsession, and she admired her almost as a muse-like figure. Although it is debated how much of their relationship was based on attraction and how much on projection of fantasies, June certainly influenced Nin’s understanding of femininity, identity, and the power dynamics within relationships. The complex triangle between Anaïs, Henry, and June is one of the key emotional and psychological dynamics in her diaries.

Themes and Philosophy of Relationships:

Nin’s relationships often transcended conventional norms of monogamy, reflecting her personal philosophy of emotional and sexual freedom. She rejected societal constraints on love, believing in the possibility of having multiple loves simultaneously, each fulfilling a different aspect of her complex emotional and intellectual needs. Her affairs were often deeply intertwined with her artistic journey, as many of her lovers, including Henry Miller and Otto Rank, served as both romantic partners and catalysts for her creative development.

Her diaries reveal her ongoing struggle to balance her desire for intense passion with the practicalities of commitment and stability. Nin’s notion of relationships was rooted in self-exploration, seeing them as mirrors through which she could understand her own desires, conflicts, and artistic identity. Psychoanalysis played a critical role in how she navigated love, with her interest in Freud, Jung, and Rank influencing her thoughts on the unconscious motivations driving human connections.

Anaïs Nin’s relationships were a central part of her life and literary identity. Her passionate affairs with individuals like Henry Miller, Rupert Pole, and Otto Rank, as well as her complex feelings for people like June Miller, reflected her desire to live outside traditional social structures. These relationships were not merely romantic or physical; they were also psychological and creative collaborations that shaped the narrative of her life, feeding into her vast body of work, especially her diaries, which remain a critical exploration of the inner life, love, and selfhood.

What psychoanalysis topics she was particularly interested in? Was she a Jungian? #

Anaïs Nin’s engagement with psychoanalysis was profound and highly influential on her personal and creative development. Her interests in psychoanalysis were diverse, but there were certain key topics and themes she was particularly drawn to, such as the exploration of the unconscious, the role of dreams, sexuality, and the process of individuation. While her relationship with psychoanalytic schools of thought evolved over time, she was notably influenced by Freudian psychoanalysis and later became more aligned with the ideas of Otto Rank, one of Freud’s students who had a distinctive approach to creativity and therapy. Nin’s connection to Carl Jung and Jungian psychology was more tangential, although she explored several Jungian concepts in her work.

Psychoanalysis and Its Role in Nin’s Life:

Nin’s engagement with psychoanalysis began as a personal exploration of her own emotional conflicts, particularly the trauma of her father’s abandonment and the complexities of her relationships. Her therapy sessions initially focused on her own psychological pain, but she soon recognized psychoanalysis as a tool for self-understanding and for enhancing her artistic creativity. For Nin, psychoanalysis was not simply about pathology; it was about tapping into the unconscious to access deeper layers of the self, something she pursued in her writing as well.

Key Psychoanalytic Topics Nin Explored:

- The Unconscious and Creativity:

The unconscious mind was one of the central areas of interest for Nin. She was fascinated by the idea that the unconscious held the key to deeper truths about human behavior, desires, and creativity. She believed that the artist’s task was to tap into this unconscious material and give it expression, much like Freud and Jung’s notion of accessing the “hidden” self. Nin saw the unconscious as a wellspring of creativity and erotic energy, often blurring the lines between these elements in her diaries and fiction.

Her work, particularly her erotic fiction, reflects this engagement with the unconscious, exploring repressed desires, hidden fantasies, and the tension between societal norms and individual drives.

- Dreams:

Dreams were another key aspect of psychoanalytic thought that fascinated Nin. Drawing on both Freud’s and Jung’s interpretations of dreams, Nin believed that dreams were windows into the unconscious and had important symbolic meanings. Dreams were not merely random or insignificant; they were rich with insight into the conflicts, desires, and repressed aspects of the self.

In her diaries, Nin often wrote about her dreams and used them as a form of self-therapy, attempting to decode their symbols and messages to understand her deeper emotions and creative impulses. Her writing was also dreamlike in style, blending reality and fantasy, much like the surreal, symbolic nature of dreams.

- Sexuality:

Freudian psychoanalysis, with its emphasis on the centrality of sexuality in human psychology, deeply influenced Nin. She was intrigued by the idea that sexual energy was a primary motivator in human life and creativity. Nin explored sexuality not just as a biological or social phenomenon, but as an essential part of the psyche that could be channeled into creative expression. Her erotic writings, including works like Delta of Venus and Little Birds, reflect her belief in the intimate connection between sexuality, power, and artistic creation.

She was also interested in the psychoanalytic view of female sexuality, particularly the ways in which women’s desires were suppressed or misunderstood in society. In her diaries and fiction, she delves into the complexity of female erotic experience, often challenging the male-centered narratives of sexual desire.

- Individuation and the Self:

While Nin was more directly influenced by Freudian and Rankian thought, she also explored Jungian themes, particularly the process of individuation. Jung’s concept of individuation, the journey toward achieving wholeness by integrating the conscious and unconscious parts of the self, resonated with Nin’s own struggles with identity and self-expression.

For Nin, individuation was not only a psychological process but also a creative one. Her writing served as a way to integrate the various, often conflicting parts of her personality—her role as a wife, lover, artist, and daughter. The search for an authentic self was a lifelong theme in her work, and she used her diaries as a tool for this inner journey, much like Jung’s idea of “active imagination” where creativity becomes a way of exploring the unconscious.

- Psychoanalysis and Artistic Creation:

Otto Rank, one of Freud’s most creative students, had a profound influence on Nin’s understanding of the relationship between psychology and art. Rank broke away from traditional Freudian thought, focusing more on the role of creativity and the artist’s confrontation with life’s anxieties, especially the fear of death. Rank argued that artistic creation was a way of dealing with existential anxiety and achieving psychological growth.

Nin was deeply inspired by Rank’s ideas about the creative process. He emphasized the importance of the will and the need to live in the present rather than merely analyzing past traumas. Nin’s diaries reflect her attempts to navigate these ideas—using writing not just to analyze herself but also to transform her understanding of her inner world into art. Rank’s belief in the therapeutic power of creativity aligned closely with her own view that artistic expression could be a form of self-healing.

What was Nin’s likely attachment style? The propensity to create philosophy around deeply personal lifestyle choices is an avoidant trademark. Do we have any reflections on their relationship evidenced by Rupert Pole? #

Anaïs Nin’s attachment style, as evidenced by her relationships and personal philosophy, appears to have been complex and likely best categorized as fearful-avoidant (also known as disorganized). This attachment style is characterized by a deep desire for intimacy, combined with a strong fear of vulnerability and rejection, leading to contradictory behaviors in relationships. Nin’s patterns of emotional intensity, alternating between closeness and distance, and her ability to compartmentalize relationships are indicative of this style.

Avoidant Tendencies and Philosophy:

You are correct in suggesting that Nin’s inclination to create a personal philosophy around her lifestyle—particularly her advocacy for emotional and sexual freedom—can be viewed as a form of avoidant behavior. Avoidant attachment styles are often linked to an intellectualization of emotional life, using philosophical justifications to maintain autonomy and avoid the vulnerability of deep emotional attachment. Nin’s insistence on her right to experience multiple loves, her rejection of traditional monogamy, and her double life with two husbands (Hugh Guiler and Rupert Pole) are examples of this tendency to avoid the full emotional entanglement that comes with exclusivity and long-term intimacy.

Nin crafted a philosophy around emotional plurality and the belief that one person could not fulfill all of an individual’s emotional or psychological needs. This philosophy allowed her to engage in intense, but ultimately compartmentalized relationships, avoiding the emotional demands that typically come with long-term monogamous commitments. This framework may have functioned as a defense mechanism, enabling her to maintain emotional control while appearing to embrace intimacy.

Early Experiences and Attachment Development:

Nin’s likely attachment style can be traced back to her early childhood experiences, particularly her father’s abandonment. As mentioned earlier, her father, Joaquín Nin, left the family when Anaïs was around 11 years old, a deeply traumatic event for her. This abandonment may have contributed to an underlying fear of being hurt or left behind, leading her to develop both a craving for intimacy and a fear of it. In her diaries, Nin often reflects on her desire to reconnect with her father, a relationship that left her with unresolved emotional wounds.

Her mother, Rosa Culmell, provided stability but was strict and conservative, which may have contributed to Nin’s inner conflict between yearning for security and desiring freedom. These early relational experiences likely played a key role in shaping her adult attachment patterns, with an underlying sense of ambivalence toward both closeness and independence.

Relationship with Rupert Pole: Evidence of Attachment Dynamics

Nin’s relationship with Rupert Pole offers valuable insight into her attachment style. Pole, a younger actor whom she met in 1947, became one of the most important people in her life, yet their relationship was marked by both closeness and distance. Nin’s dual life—maintaining two marriages simultaneously, one with Pole and one with Hugh Guiler—reveals her ambivalent approach to intimacy.

Rupert Pole as a Safe Haven: Pole seems to have provided Nin with a nurturing, emotionally available presence, which she craved. By all accounts, Pole adored Nin and was devoted to her, creating a safe emotional space for her. Nin found comfort in Pole’s presence, and he became a source of emotional support during the later years of her life. This reflects her desire for attachment, as she needed someone who could offer security, warmth, and emotional attention.

Compartmentalization and Distance: At the same time, Nin was unwilling to fully commit herself to Pole alone. Even though she married him in 1955 (despite never officially divorcing Guiler), she maintained her double life, shuttling between Pole in California and Guiler in New York. Nin’s ability to split her emotional life between two men suggests an avoidance of deep, singular intimacy with any one person. Rather than facing the potential emotional intensity and vulnerability of monogamy, Nin seemed to create multiple relationships that allowed her to maintain a sense of autonomy and emotional distance.

Self-Reflective Nature of the Diaries: In her diaries, Nin reflects on the tension between her need for intimacy and her fear of being overwhelmed by it. She was often torn between a desire for emotional closeness and the simultaneous need for space and freedom. This ambivalence is typical of the fearful-avoidant attachment style, where individuals crave love but fear the vulnerability that comes with it.

Fearful-Avoidant Dynamics:

Nin’s attachment behaviors fit well with what psychologists now describe as the fearful-avoidant (disorganized) attachment style, which involves a complex mix of longing for emotional closeness and a simultaneous tendency to avoid it out of fear of rejection or engulfment. Key characteristics of this attachment style that apply to Nin include:

Intense, Short-Term Romantic Liaisons: Nin engaged in passionate love affairs (such as those with Henry Miller and Gonzalo Moré) but struggled with long-term emotional commitment. She often withdrew emotionally after a period of intense connection, only to seek out new, stimulating relationships.

Compartmentalization of Relationships: Nin’s ability to live a double life—being married to two men without either one fully knowing the extent of her other relationships—demonstrates an avoidance of emotional entanglement. By keeping parts of her life separate, she could maintain emotional control and avoid the full intensity of deep, singular attachment.

Philosophical Justifications: Nin’s personal philosophy of emotional plurality, which justified her simultaneous relationships, can be viewed as an intellectualization of her attachment needs. This is a common strategy among avoidant individuals, who often rationalize their behaviors as part of a personal belief system rather than as stemming from psychological defenses.

Fear of Rejection and Abandonment: Nin’s fear of abandonment, likely rooted in her childhood trauma, may have made her wary of depending too much on any one partner. This fear can cause individuals to avoid the kind of emotional closeness that could lead to pain if the relationship fails.

Reflections on the Relationship with Rupert Pole:

Pole himself, after Nin’s death, commented on their relationship with a sense of loyalty and admiration. He described Nin as both loving and elusive, and while he clearly adored her, he also noted that she was often emotionally distant. After her death, Pole was responsible for helping to edit and publish her unexpurgated diaries, revealing more of her internal struggles with intimacy and the complexity of her romantic life. Pole’s reflections on their relationship suggest that while Nin found solace in his affection, she was never fully able to commit to a singular, emotionally exclusive bond.

Anaïs Nin’s attachment style was likely fearful-avoidant, characterized by a deep desire for intimacy and connection, combined with a fear of emotional vulnerability and rejection. Her relationships with men like Rupert Pole, Henry Miller, and Hugh Guiler show a pattern of seeking closeness while maintaining emotional distance, often rationalizing these behaviors through a personal philosophy of emotional freedom. Nin’s childhood experiences of abandonment, her intense but short-lived affairs, and her compartmentalized relationships all point to a complex interplay of desire and avoidance in her emotional life.

Is it possible to trace, from Nin’s self-reflective writing, her alternating between the four roles we explored earlier regarding Virginia Woolf and Anne Sexton? The roles are: observer, protector, persecutor and child. #

Anaïs Nin’s self-reflective writing, particularly her diaries, offers a rich tapestry through which we can trace her movement between various psychological and emotional roles. The four roles you mentioned—observer, protector, persecutor, and child—are especially relevant in understanding her inner dynamics, as they reflect the oscillation between conflicting desires for independence, intimacy, control, and vulnerability. Much like Virginia Woolf and Anne Sexton, Nin’s personal reflections reveal her struggles with identity, relationships, and creativity, and she embodies these roles in different contexts throughout her life.

- The Observer:

The role of the observer is perhaps the most central to Nin’s identity, both as a diarist and a writer. In her diaries, Nin often adopts a detached, analytical stance, using her writing as a way to observe not only her surroundings but also her own emotional reactions and the behavior of those around her. Her role as an observer is closely linked to her desire for self-understanding and her psychoanalytic explorations.

Self-Reflection and Intellectualization: Nin’s diaries are full of moments where she steps back from emotional entanglements and reflects on them with a sense of intellectual curiosity. Her need to understand her own desires, fears, and motivations leads her to meticulously document her internal states. This role of the observer allows her to maintain a certain level of distance from her emotions and relationships, giving her control over them through the act of writing.

In Relationships: As an observer, Nin often analyzes her lovers and friends, placing them under the microscope of her introspection. This is especially evident in her relationship with Henry Miller and Rupert Pole, where she examines not only her own feelings but also their personalities and the psychological dynamics of their interactions. The observer role provides Nin with a way to remain somewhat aloof, even as she immerses herself in intense relationships.

The Psychoanalytic Lens: Nin’s engagement with psychoanalysis further emphasizes her role as an observer. With figures like Otto Rank, she explored the depths of her unconscious and her relationships, often treating her own psyche as a subject of study. This aligns with the observer’s inclination to analyze rather than simply experience emotions.

- The Protector:

The protector role in Nin’s life emerges through her relationships with both her lovers and herself. Nin saw herself as a protector of her creative spirit, often shielding it from external judgment and societal norms, and she also extended this protective role to the people in her life, especially when she felt they were misunderstood or needed her support.

In Relationships: Nin frequently took on the protector role in her romantic relationships, particularly with Henry Miller and Gonzalo Moré. With Miller, she offered financial and emotional support, becoming his advocate when his work was underappreciated or unpublished. She saw herself as a protector of his genius, often going out of her way to promote and support his literary ambitions, even when it cost her personally.

Self-Protection: Nin was highly protective of her inner life, creating layers of secrecy and compartmentalization to guard her emotional independence. Her double life with Rupert Pole and Hugh Guiler is a clear manifestation of this protective instinct. By maintaining two separate marriages and lives, she was able to protect her autonomy, insulating different aspects of herself from each other to avoid emotional overwhelm. This can also be seen in the way she guarded her diaries, carefully curating what was published during her lifetime and what remained private.

Protecting Her Creative Identity: Nin was also fiercely protective of her artistic identity, resisting the pressures of societal norms that tried to define or constrain her. In her diaries, she frequently reflects on the importance of preserving her creative voice against the demands of conventional life and relationships. She often positioned herself as the protector of her own artistic freedom, ensuring that no one—whether a lover, friend, or societal expectation—could encroach on her creativity.

- The Persecutor:

The role of the persecutor appears in Nin’s writing through her more self-critical and judgmental moments. Nin often vacillated between moments of intense self-doubt and self-assertion, and in her diaries, we can see her grappling with feelings of guilt, shame, and self-recrimination, particularly in relation to her personal choices and relationships.

Self-Judgment: Nin could be extremely hard on herself, especially when she felt torn between her desires and societal expectations. Her lifestyle—living two separate marriages, engaging in multiple love affairs, and pursuing artistic freedom—sometimes led her to moments of intense guilt and inner conflict. This self-persecution is evident in her diary entries where she questions her own actions and motives, reflecting on whether she is being fair to those she loves, or whether she is using them for her own emotional and creative needs.

In Relationships: Nin also experienced moments where she played the persecutor in her relationships, particularly when she felt disappointed by her lovers or when they failed to meet her expectations. In her diaries, she often scrutinizes the weaknesses and failures of her partners, such as Henry Miller’s selfishness or Gonzalo Moré’s instability, occasionally placing them in a negative light when they fall short of her ideals. However, this role was often tempered by her intellectual understanding of human frailty, making her judgment of others more reflective than harsh.

- The Child:

The child role is closely tied to Nin’s feelings of vulnerability, dependency, and her unresolved emotional trauma from childhood, especially her father’s abandonment. The child role is one where Nin expresses her need for care, protection, and emotional validation, often seeking these in her romantic relationships.

Emotional Dependency: In several of her relationships, particularly with Otto Rank and Rupert Pole, Nin took on the role of the child, seeking emotional support, care, and validation. With Rank, she allowed herself to be vulnerable, both in therapy and in their romantic connection, revealing her need for guidance and emotional healing. With Pole, she sought a more nurturing relationship, where she could be cared for without the pressures of intellectual or emotional competition.

Father Complex: Nin’s unresolved feelings toward her father, Joaquín Nin, are perhaps the most overt expression of her child role. In her diaries, she often writes about the pain of her father’s abandonment and her longing to be reunited with him, even going so far as to engage in a brief, incestuous relationship with him later in life as a way of confronting and resolving these deep emotional wounds. Her relationship with her father placed her firmly in the role of the child, seeking his love and approval but also experiencing the deep hurt of his rejection.

Creative Playfulness: The child role also emerges in Nin’s approach to creativity. She embraced a sense of playfulness and spontaneity in her writing, often describing her artistic process as a return to a more primal, innocent state. This childlike freedom in creativity allowed her to explore her unconscious without the constraints of adult rationality or societal expectations.

Anaïs Nin’s self-reflective writing reveals a continual shifting between the roles of observer, protector, persecutor, and child, depending on the context of her relationships and her inner psychological needs.

As the observer, she maintained a degree of detachment, intellectualizing her emotions and relationships through her diaries and psychoanalytic lens. In the role of the protector, she safeguarded her creative autonomy and the emotional well-being of her lovers, while also shielding herself from the vulnerabilities of deep attachment.

As the persecutor, she grappled with self-criticism, guilt, and disappointment in both herself and others, often reflecting on her emotional conflicts with intensity. Finally, as the child, she expressed her deepest needs for care, validation, and emotional security, revealing her unresolved childhood traumas and desire for nurturing in her romantic relationships.

Nin’s life and writing are marked by this fluidity between roles, illustrating her deep complexity as both a person and an artist. The contradictions and tensions within her inner world were the very source of her creative energy, driving her to explore the depths of human experience in her diaries and fiction.