An unsettling novel exploring themes of isolation, childhood, and the darker, taboo elements.

An unsettling novel exploring themes of isolation, childhood, and the darker, taboo elements.

Cement Garden #

Tell me about Ian McEwan’s novel The Cement Garden? #

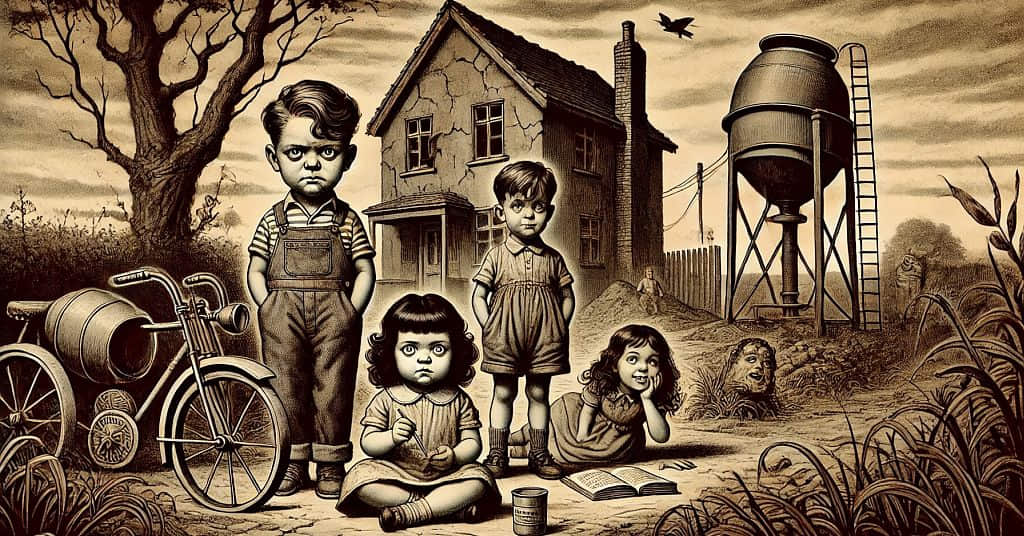

The Cement Garden (1978) by Ian McEwan is a striking and unsettling novel that explores themes of isolation, childhood, and the darker, often taboo elements of human psychology. It is a story that delves into the collapse of family structure, both literally and figuratively, after the death of the parents in a dysfunctional family.

Plot Overview:

The novel is set in a desolate, unnamed suburb and centers around four children—Jack, Julie, Sue, and Tom—who find themselves orphaned after the deaths of their father and mother. The father’s death occurs first, due to illness, and the mother soon follows, leaving the children alone in the family home. Rather than face the threat of separation by social services, the siblings decide to hide their mother’s death by encasing her body in cement in the cellar.

The novel is narrated by Jack, the eldest son, whose voice is detached, almost clinical, which adds to the haunting quality of the story. The narrative tracks the siblings’ increasingly bizarre behavior as they try to maintain a semblance of normalcy while their world descends into chaos. The house itself becomes a decaying, claustrophobic space that mirrors the psychological disintegration of the children.

Themes:

Isolation and Decay: The setting—an abandoned house surrounded by wasteland—mirrors the emotional and psychological isolation of the children. As the house deteriorates, so do the characters, both physically and mentally. McEwan explores how isolation, both literal and emotional, can deform the psyche.

Innocence and Corruption: The novel blurs the boundaries between childhood innocence and moral corruption. The children’s efforts to maintain their autonomy lead to increasingly disturbing actions, challenging traditional moral and social boundaries. Their isolation leads them to develop their own skewed sense of morality.

Familial Relationships: The novel examines family dynamics in an extreme context. Without their parents, the older siblings, Jack and Julie, take on parental roles, yet their relationship becomes disturbingly complex, culminating in a quasi-incestuous bond that highlights the breakdown of conventional familial boundaries.

Psychosexual Development: McEwan does not shy away from exploring the children’s burgeoning sexual awareness, especially Jack’s. His adolescence is marked by a combination of confusion, repression, and voyeurism, as he navigates the strange new emotional terrain created by the absence of parental authority and social norms.

Death and Repression: The encasement of the mother’s corpse in cement becomes a central symbol for repression—literally burying trauma and grief in an attempt to avoid facing it. It also speaks to the psychological impulse to preserve the family unit, even at a grotesque cost. The cemented corpse represents the children’s unwillingness to let go of the past and their desire to cling to some semblance of control over their lives.

Narrative Style:

McEwan’s prose in The Cement Garden is stark and minimalist, with a detached and matter-of-fact tone that enhances the macabre events of the story. The narrative’s emotional restraint allows the horrific nature of the children’s actions to emerge more gradually, lending the novel an almost clinical examination of their psychological deterioration. This dispassionate voice contrasts with the deeply unsettling subject matter, adding to the novel’s eerie atmosphere.

Critical Reception:

The Cement Garden was both praised and criticized upon its release. Many admired McEwan’s boldness in tackling taboo subjects, particularly the exploration of repressed sexuality and the darker aspects of human nature. However, some found the novel disturbing and questioned the ethics of its content. Despite the controversy, The Cement Garden established McEwan as a provocative and fearless writer willing to explore the uncomfortable edges of human experience.

The novel’s exploration of themes like sexual awakening, isolation, and the fragility of the family unit make it one of McEwan’s most complex and psychologically probing works. Its transgressive content, dark tone, and chilling examination of human behavior render it a memorable but disquieting read.

From what angle was the ethics of the novel’s content criticised? #

The ethical criticisms of The Cement Garden largely centered around its treatment of taboo subjects, particularly incest, sexual awakening, and the portrayal of disturbed children. These criticisms can be understood from several perspectives:

- Moral Transgression and Incest:

One of the most prominent ethical concerns was the depiction of incest between the elder siblings, Jack and Julie. Incest is one of society’s most deeply ingrained taboos, and McEwan’s narrative handles it without sensationalism, but also without condemnation. Some readers and critics questioned whether the novel’s neutral tone might be ethically problematic, as it seemed to avoid taking a clear moral stance on such a deeply unsettling subject. The lack of overt judgment on the part of the narrator or the narrative structure allowed the incestuous relationship to be presented as a natural progression of the siblings’ deteriorating situation. This ambiguity made some critics uneasy, fearing that McEwan was engaging in moral relativism or even titillation.

The novel’s unsettling portrayal of childhood innocence corrupted by isolation and the absence of social norms also raised ethical concerns. The incest between Jack and Julie, while emerging as part of their psychological breakdown, was seen by some as ethically questionable because McEwan presents it within the confines of a decaying domestic sphere, without giving moral cues for the reader to latch onto.

- Sexualization of Children:

Another major point of criticism revolved around McEwan’s depiction of the children’s burgeoning sexuality, particularly Jack’s. The novel includes scenes where Jack engages in masturbation and voyeurism, which some critics found uncomfortable, particularly given his youth. The frank, almost clinical way in which McEwan presents these scenes was seen by some as ethically troubling, as it placed the reader in a position of voyeurism themselves, forcing them to confront uncomfortable realities about childhood and adolescence without the comfort of narrative distance or moral framing.

Some critics accused McEwan of being exploitative, using shock value by focusing on the children’s sexual curiosity and development in a context devoid of any adult guidance or moral structure. In particular, scenes involving the youngest sibling, Tom, who dresses in girls’ clothing and experiments with his gender identity, were seen by some as a potential ethical overstep in treating children’s sexuality and identity without adequate sensitivity.

- The Portrayal of Death and Grief:

The handling of the mother’s death and the children’s decision to encase her body in cement also raised ethical questions. Critics argued that McEwan was treading a fine line between exploring the psychological impact of grief and crossing into morbid sensationalism. The children’s practical, almost cold reaction to their mother’s death, along with the grotesque act of sealing her body in cement, was seen by some as ethically problematic in its depiction of children dealing with trauma. Instead of engaging with grief in a manner that might evoke sympathy or sorrow, the novel’s stark, emotionally detached portrayal made some readers feel disturbed by what seemed to be a callous disregard for human dignity.

- Normalization of Dysfunctional Behavior:

Some critics worried that the novel, through its emotionally neutral tone and lack of explicit moral judgment, might normalize or even subtly endorse dysfunctional and transgressive behaviors. The children’s growing isolation, moral decay, and psychological detachment from the world around them are presented in a manner that, while deeply disturbing, does not come with a clear ethical reckoning or critique. The concern was that readers might interpret this lack of moral direction as a form of relativism, where extreme behaviors, including incest and the desecration of the mother’s body, are not condemned but simply depicted as a byproduct of their circumstances.

- Question of Exploitation:

Some critics argued that McEwan was exploiting shocking subject matter for artistic or literary effect, using the themes of incest, death, and childhood sexual development primarily to provoke or disturb. These critics felt that the novel’s focus on the morbid and taboo aspects of the human condition was more about creating shock value than engaging in an ethically thoughtful exploration of those themes. The concern was that The Cement Garden might be exploiting the inherent discomfort surrounding these issues to manipulate readers emotionally, rather than treating them with the necessary depth and moral consideration.

- Childhood as a Vehicle for Darkness:

Lastly, some critics questioned the ethics of McEwan’s portrayal of childhood itself. The novel’s children are depicted as fundamentally corrupted by their isolation, as if left to their own devices, human beings—particularly children—would inevitably devolve into morally degenerate beings. The ethical critique here hinges on whether McEwan’s vision of childhood is too bleak and misanthropic, perhaps perpetuating an overly dark and cynical view of human nature, especially in terms of how children might behave without societal constraints.

Counterpoints to the Criticism:

Defenders of the novel argue that McEwan’s treatment of these difficult subjects is not exploitative or unethical, but rather an honest and courageous examination of human behavior under extreme conditions. They contend that McEwan does not celebrate or normalize the disturbing events, but rather presents them in a manner that forces the reader to grapple with uncomfortable truths about isolation, family, and the darker impulses that can emerge when social norms disintegrate. The ethical ambiguity, rather than being a flaw, is seen by some as a reflection of the complexity of human experience.

In summary, the ethical criticism of The Cement Garden largely revolves around its portrayal of taboo subjects, especially incest and childhood sexuality, and the concern that McEwan’s detached narrative style fails to provide a clear moral framework, potentially making readers uncomfortable with how the novel approaches these dark themes without guiding them toward a moral or ethical resolution.

Let’s compare this novel to Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin? #

The Cement Garden by Ian McEwan and We Need to Talk About Kevin (2003) by Lionel Shriver are both dark, psychologically intense novels that explore the breakdown of family, but they approach their themes from very different angles and with distinct narrative styles. Despite their differences, there are key parallels and contrasts between the two that make for an interesting comparison, especially in how they handle themes of familial disintegration, moral ambiguity, and the psychology of children or adolescents in a dysfunctional environment.

- Narrative Voice and Structure:

The Cement Garden: The novel is narrated in the first person by Jack, a detached and emotionally stunted teenager who describes the gradual disintegration of his family with an eerie, almost clinical tone. McEwan’s minimalist style heightens the unsettling atmosphere by refusing to directly comment on the morality of the characters’ actions. Jack’s perspective is limited, and his unreliable narration leaves much of the psychological complexity implied rather than explained. The reader is invited to fill in the gaps, which enhances the novel’s ambiguous moral landscape.

We Need to Talk About Kevin: Shriver’s novel is epistolary, told through letters written by Eva, Kevin’s mother, to her estranged husband, Franklin. This structure gives the reader direct access to Eva’s internal turmoil, guilt, and existential reflections on motherhood. The confessional tone and retrospective analysis make the novel deeply introspective, often agonizingly so. Eva’s unreliability is of a different sort; her perspective is colored by hindsight, guilt, and resentment. Unlike McEwan’s emotionally detached style, Shriver engages the reader with an intense emotional and moral reckoning as Eva tries to understand whether Kevin’s violent behavior is the result of her parenting or something innate within him.

Comparison: While The Cement Garden has an emotionally cold, almost dispassionate voice that distances the reader from the characters’ interiority, We Need to Talk About Kevin is emotionally raw and introspective. Both narrators are unreliable in their own ways, but whereas Jack’s unreliability stems from his emotional repression and detachment, Eva’s comes from her subjective, self-critical lens, grappling with guilt and responsibility.

- Themes of Isolation and Family Disintegration:

The Cement Garden: The novel deals with the literal and emotional isolation of four siblings who, after the death of their parents, are left to fend for themselves in a decaying house. Their physical isolation from the outside world mirrors their psychological isolation from societal norms, leading them to develop their own skewed family dynamic. The siblings’ relationships devolve into dysfunction, and the incestuous bond between Jack and Julie epitomizes the collapse of moral and familial boundaries. Isolation becomes both the cause and symptom of the children’s descent into a morally gray existence.

We Need to Talk About Kevin: While Kevin is not about physical isolation, it delves into emotional and psychological isolation within a family unit. Eva feels disconnected from her son, Kevin, from birth, and their relationship is marked by a profound emotional chasm. This estrangement is exacerbated by Franklin’s refusal to acknowledge Kevin’s disturbing behavior, creating a divided family in which Eva is left to navigate her growing fears and suspicions about Kevin alone. Kevin’s later massacre at his high school is the tragic culmination of years of emotional disintegration within the family. The novel explores how isolation within the family can contribute to violence and tragedy, albeit in a different form than in The Cement Garden.

Comparison: Both novels explore the idea that family can become an isolating space, rather than a nurturing one. In The Cement Garden, the isolation is more physical and environmental, leading to moral collapse. In Kevin, it’s more psychological and emotional, leading to violence and estrangement. In both cases, the family becomes a claustrophobic space where repressed emotions and moral decay take root.

- Psychosexual Development and Violence:

The Cement Garden: McEwan’s novel is deeply concerned with the psychosexual development of its characters, particularly Jack. His confused sexual awakening, incestuous relationship with Julie, and voyeuristic tendencies are central to the story. The absence of parental authority and societal norms allows the siblings to drift into morally ambiguous territory, where normal boundaries of sexuality, power, and control dissolve. Jack’s psychological development is closely tied to his sense of isolation and the breakdown of familial roles.

We Need to Talk About Kevin: Shriver’s novel focuses on the development of Kevin as a morally disturbed individual, whose behavior from a young age suggests a deep-seated capacity for violence. The novel raises questions about nature versus nurture, and whether Kevin’s psychopathy is the result of his mother’s ambivalence toward him or something inherent in his personality. While the novel doesn’t focus explicitly on psychosexual themes like The Cement Garden, Kevin’s manipulative, violent tendencies can be seen as a kind of warped emotional development, driven by a desire for control and power, not unlike the psychological breakdown of Jack in McEwan’s novel.

Comparison: Both novels examine how disturbed children or adolescents develop in environments devoid of healthy familial relationships. In The Cement Garden, the focus is on sexual confusion and moral ambiguity, while in Kevin, it’s on the development of violent psychopathy. In both cases, the breakdown of family boundaries leads to the transgression of societal norms, whether through incest or mass violence.

- Role of the Mother:

The Cement Garden: The mother in The Cement Garden dies early in the novel, but her absence looms large over the story. The children, particularly Jack and Julie, struggle to fill the parental void, but their efforts are marked by confusion and dysfunction. The lack of a maternal figure leaves the children directionless, untethered from any moral or social compass. The decaying house and the cemented corpse of their mother become symbolic of the buried emotions and unresolved grief that pervade their lives.

We Need to Talk About Kevin: The role of the mother is central in Kevin, with the entire narrative revolving around Eva’s reflection on her role in Kevin’s development. Eva’s ambivalence toward motherhood is a central theme, and the novel raises difficult questions about maternal responsibility, guilt, and whether a mother’s love—or lack thereof—can shape a child’s moral compass. Unlike in The Cement Garden, the mother here is alive and active, but her emotional estrangement from Kevin becomes the focal point of the novel’s psychological exploration.

Comparison: In The Cement Garden, the absence of the mother creates a vacuum that leads to moral decay, while in We Need to Talk About Kevin, the mother’s emotional estrangement from her child plays a key role in the formation of Kevin’s violent character. In both novels, the maternal figure—or lack thereof—is crucial to understanding the children’s psychological development and the ultimate collapse of the family unit.

- Moral Ambiguity:

The Cement Garden: McEwan’s novel leaves much of its moral commentary implied. The detachment of the narrative voice creates an ethical ambiguity, as readers are left to interpret the actions of the children—particularly the incestuous relationship—without clear moral guidance from the text. The lack of overt judgment makes the novel morally unsettling, as it presents taboo actions in a matter-of-fact way.

We Need to Talk About Kevin: Shriver’s novel, while also morally complex, is more explicit in its engagement with ethical questions. Eva’s reflections on her own role in Kevin’s actions invite readers to grapple with questions of parental responsibility, guilt, and the nature of evil. The novel doesn’t offer easy answers but is more directly concerned with the ethical ramifications of Kevin’s violence and Eva’s failures as a mother.

Comparison: Both novels are morally ambiguous, but We Need to Talk About Kevin is more overt in its ethical exploration, particularly regarding motherhood and responsibility. The Cement Garden, by contrast, leaves more room for reader interpretation, with its disturbing events presented in a detached, almost amoral light.

Both The Cement Garden and We Need to Talk About Kevin are haunting, psychologically complex novels that explore the breakdown of family and the darker aspects of human behavior. However, they differ in their narrative styles, thematic focus, and treatment of moral ambiguity. McEwan’s novel is more about the internal collapse of moral boundaries in the absence of societal norms, while Shriver’s novel is a broader exploration of parental guilt, responsibility, and the nature of evil. Both novels challenge readers to confront uncomfortable truths about the family and the human psyche, albeit through very different lenses.

“We Need to Talk About Kevin” was made into a movie. What about “The Cement Garden”? #

Yes, The Cement Garden was also adapted into a film. The novel was made into a movie in 1993, directed by Andrew Birkin, a British filmmaker and screenwriter. Birkin was closely involved in the adaptation process, both directing and writing the screenplay, which allowed him to stay fairly true to the novel’s unsettling atmosphere and narrative complexity.

The 1993 Film Adaptation:

- Director: Andrew Birkin

- Cast: Charlotte Gainsbourg as Julie, Andrew Robertson as Jack, Alice Coulthard as Sue, Ned Birkin as Tom, Sinéad Cusack as the Mother

The adaptation received positive critical attention for capturing the novel’s eerie, claustrophobic atmosphere and for its unflinching portrayal of the darker psychological elements. Charlotte Gainsbourg’s performance as Julie was particularly noted, as she captured the character’s combination of maturity and vulnerability. Andrew Robertson, who played Jack, also delivered a strong performance, embodying the character’s emotional detachment and troubled adolescence.

Themes and Tone in the Film:

Like the novel, the film delves into the psychological disintegration of the children after the deaths of their parents, maintaining the novel’s focus on isolation, decay, and moral ambiguity. The tone of the movie is similarly stark, detached, and unsettling, which matches McEwan’s narrative style. The decision to preserve much of the novel’s minimalist dialogue and quiet, introspective moments allows the film to retain the novel’s sense of unease and creeping dread.

However, one of the challenges with the adaptation was translating the internal, psychological depth of Jack’s narration onto the screen. McEwan’s novel is rich with Jack’s inner turmoil and confused emotions, much of which is difficult to capture visually. Birkin chose to focus on the physicality of the decaying environment and the interactions between the siblings to convey the emotional weight of the story. As a result, the film relies heavily on atmosphere, visual metaphors, and the use of space to evoke the psychological states of the characters.

Controversies:

Like the novel, the film’s handling of incest and other taboo subjects stirred controversy. The portrayal of the incestuous relationship between Jack and Julie is depicted in the film, and although it is not sensationalized, it is shown in a frank, unflinching manner. This element of the story provoked some discomfort among audiences and critics, though many appreciated the film’s commitment to staying true to the novel’s themes and its refusal to shy away from the darker aspects of the story.

Reception:

The film received generally favorable reviews for its strong performances, atmospheric direction, and its fidelity to McEwan’s novel. Andrew Birkin won the Silver Bear for Best Director at the 1993 Berlin International Film Festival for his work on the film. Despite its positive reception among critics, The Cement Garden remained more of a cult film due to its unsettling content, rather than achieving widespread commercial success.

Much like We Need to Talk About Kevin, The Cement Garden was successfully adapted into a film, though its darker, more abstract psychological content posed significant challenges in adaptation. Both films remain relatively faithful to their respective novels, preserving the intense emotional and moral complexities that define them. However, The Cement Garden’s unsettling themes of isolation, incest, and moral decay made it a more controversial and niche cinematic experience compared to We Need to Talk About Kevin.