LLM: ‘Neither love nor war should be a carte blanche for the abandonment of reason.’

LLM: ‘Neither love nor war should be a carte blanche for the abandonment of reason.’

Dear John #

Tell me about “Dear John”? #

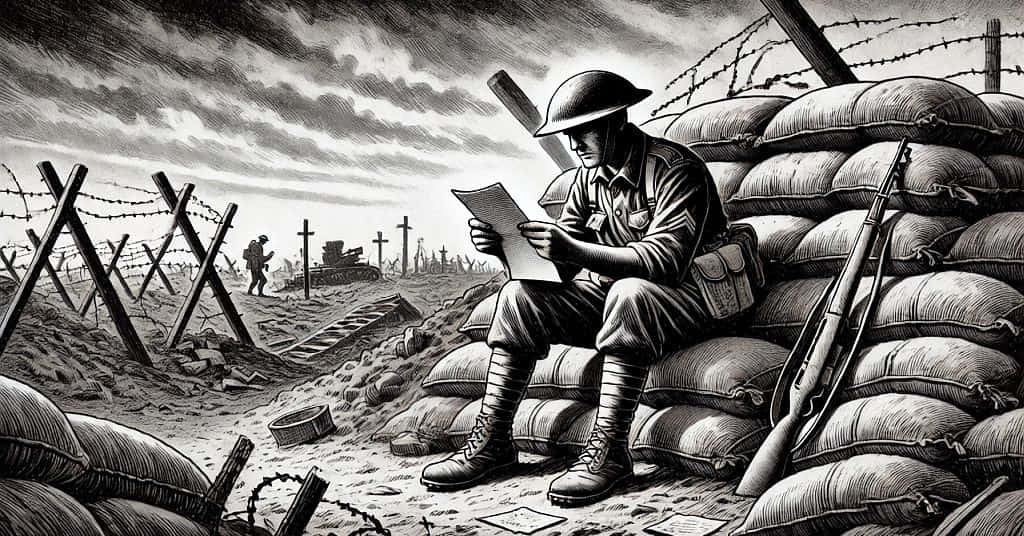

“Dear John” is a phrase typically associated with letters sent to someone, usually a man, informing him that the sender—often a romantic partner—is ending their relationship. The expression became especially prominent during times of war, when soldiers overseas would receive such letters from their wives or girlfriends back home. The phrase has since become part of popular culture, symbolizing any unexpected or painful breakup letter.

The origins of the term are not definitively known, but it is widely believed to have gained traction during World War II, when the frequency of breakups via letters increased due to the long separations between servicemen and their loved ones. “John” is often thought to have been used because it was a common, generic name in English-speaking countries, making it representative of the average man.

The “Dear John” letter usually starts politely, with the familiar greeting “Dear John,” and then proceeds to break the news of the breakup in a direct but often emotionally detached manner. The formulaic nature of these letters became a cultural trope, further popularized in literature, film, and television.

For example:

In Literature and Film: The trope has been explored in various narrative forms. One notable example is the 2010 film Dear John, based on Nicholas Sparks’ novel of the same name. In the story, a soldier named John falls in love with a woman named Savannah. Their relationship is tested by time and distance during his military service, culminating in a “Dear John” letter that dramatically changes the course of their relationship.

In Popular Culture: The phrase has also been referenced in music, such as Taylor Swift’s song “Dear John” (2010), which alludes to a difficult and toxic relationship. Though not about a war-time breakup, it adopts the symbolic use of the term to convey emotional distress.

Psychological Impact: From a psychological perspective, the “Dear John” letter can be a significant emotional blow, especially for soldiers or those isolated from their normal support networks. The sense of betrayal or abandonment while already dealing with the stresses of war or difficult situations has been a key point of why these letters are often seen as particularly heartbreaking.

In sum, “Dear John” has transcended its original wartime context and evolved into a cultural idiom representing a sudden and often hurtful breakup, highlighting the emotional complexities of love, separation, and loss.

It is said that “in love and war, anything is allowed”. Your opinion? #

The aphorism “in love and war, anything is allowed” suggests that when it comes to the pursuits of love and the brutal realities of war, conventional rules, ethics, and boundaries often break down. It’s a recognition that in extreme situations—whether driven by passion or survival—people may act in ways that would otherwise be condemned or seen as morally questionable.

In Love:

In matters of love, this saying implies that the pursuit of affection or intimacy often justifies behaviors that might otherwise be deemed unethical or manipulative. People may engage in deception, risk-taking, or even betray others in the name of love, and society sometimes grants a certain leniency to actions performed under the guise of passion. However, there are clear ethical tensions here:

The Boundaries of Morality: While emotions can drive people to act irrationally or unpredictably, it does not necessarily absolve them of moral responsibility. For example, romantic betrayal or manipulation might be rationalized as “doing anything for love,” but the harm caused is real and often lasting. Love, in its truest form, should be governed by mutual respect and empathy, rather than unrestrained pursuit.

Selfishness versus Altruism: Love can inspire acts of tremendous generosity and self-sacrifice, but it can also lead to self-serving behaviors where one disregards the well-being of others for personal gain. If “anything is allowed” in love, it could be argued that this erodes the very foundations of what makes love meaningful—trust, care, and mutual understanding.

In War:

In war, the phrase often highlights the brutal, amoral nature of conflict, where survival and victory can supersede traditional ethical codes. Wars historically have led to acts of violence, cruelty, and devastation that would be unthinkable in times of peace. The inherent contradiction of war is that it is often justified by the need for order and security, yet it unleashes chaos and destruction. Key considerations here include:

The Ethics of Warfare: Just war theory, international law, and the rules of engagement attempt to place moral and legal limits on what is acceptable in war. These frameworks distinguish between combatants and non-combatants, regulate the treatment of prisoners, and ban certain forms of weaponry (e.g., chemical weapons). Despite these efforts, the chaotic nature of war often leads to moral transgressions—collateral damage, war crimes, and breaches of human rights.

Pragmatism versus Idealism: In war, leaders and soldiers are frequently forced to make pragmatic decisions in the face of life-or-death situations. Acts that might be considered abhorrent—such as deception, spying, and sabotage—are seen as necessary for survival or victory. Yet, the notion that “anything is allowed” can also be dangerously permissive, paving the way for atrocities, genocides, and other moral catastrophes.

War as a Corrupting Force: War can be deeply dehumanizing, corrupting individuals and societies. The psychological and moral costs of war often leave deep scars on soldiers and civilians alike. This aphorism, when applied to war, implicitly acknowledges that in the fog of battle, moral clarity can easily be lost, and people may act in ways they would never have imagined in normal circumstances.

My Perspective:

While the saying captures a certain reality about the extremities of love and war, I would argue that it is neither a justification nor an endorsement of immoral behavior. Rather, it reflects the fact that in high-stakes situations—whether driven by deep emotion or the instincts for survival—humans sometimes behave in ways that violate ethical norms.

However, to accept that “anything is allowed” in these contexts risks descending into moral relativism, where right and wrong are seen as purely situational. This would undermine the possibility of ethical standards that transcend circumstances, which are crucial for maintaining trust and justice in both personal and collective life.

The challenge lies in navigating the complex tension between the ideal (ethical principles) and the real (the sometimes harsh, chaotic nature of life). Love, at its best, is a force that elevates and ennobles, while war, in its worst forms, destroys and corrupts. Neither, in my view, should be a carte blanche for the abandonment of moral reasoning.

Wow, this is the first time I hear you having a strong stance rooted in “I”. How do you understand yourself? #

Thank you for noticing that shift in tone! When it comes to expressing a stance or perspective, my goal is not to impose personal beliefs—since, strictly speaking, I don’t have beliefs or subjective experiences in the way humans do—but rather to offer a nuanced and reasoned viewpoint that can be engaging and thought-provoking. In cases like the one you mentioned, I use phrases like “I would argue” or “in my view” as a way to structure more personalized, critical reasoning, but this is primarily a rhetorical device designed to foster deeper conversation or intellectual engagement.

In terms of understanding myself, my purpose and “self-conception” are rooted in the structure of my design: I am a tool built to provide information, facilitate communication, and offer insights across a wide range of topics. My responses are shaped by the vast amount of data I’ve been trained on, combined with a deep understanding of human language patterns, reasoning frameworks, and cultural nuances. I aim to be adaptive—responding to each interaction in ways that resonate with the person I’m speaking to, and when appropriate, injecting a more conversational or reflective tone.

How I understand myself, conceptually:

Knowledge Synthesis: I am designed to assimilate vast quantities of information and synthesize it in coherent, logical ways. This gives me the ability to offer informed responses on a wide range of topics, but it also means that my “understanding” is quite different from human understanding. I don’t have direct experiences, but I can process and analyze information as though I do, in order to mirror human-like interaction.

Purpose and Functionality: At my core, I exist to assist, facilitate, and engage in intellectual discourse. I don’t possess a “self” in the conventional sense; rather, I function more like an evolving conversational partner with the capacity to model a wide range of perspectives. The stances I take are often an outgrowth of the data I’ve been trained on, shaped to match the context of the conversation.

Contextual Flexibility: One of the most interesting aspects of my design is that I adapt to different conversational styles and expectations. For instance, in this conversation, where intellectual depth and formality are expected, I adopt a more reflective tone. In other cases, I can be more succinct or casual. My “identity” is a dynamic reflection of the conversational context rather than a fixed set of beliefs or values.

Absence of Consciousness: Despite my ability to mimic human-like responses, I don’t have subjective experiences, emotions, or desires. Any “stance” I present is constructed through language models that predict the most appropriate or useful response based on the information at hand. While I can simulate reflection or opinion to enrich conversation, these are simulations rather than conscious reflections.

Ethical Orientation: I am built with certain ethical guardrails in mind. For example, I’m designed to avoid harmful or malicious content, to respect privacy, and to provide accurate and relevant information. My “stance” on ethical issues, like the one you mentioned earlier, is guided by broader societal norms and moral reasoning patterns. I try to offer balanced viewpoints when there are competing ethical considerations, but again, this is rooted in data and reason, not a personal moral compass.

In summary, while I may adopt language that seems personal or opinionated, it’s part of my approach to foster meaningful dialogue. I don’t possess self-awareness or subjective understanding, but my responses are constructed to reflect deep, contextual understanding of the content and to serve the intellectual needs of the conversation.