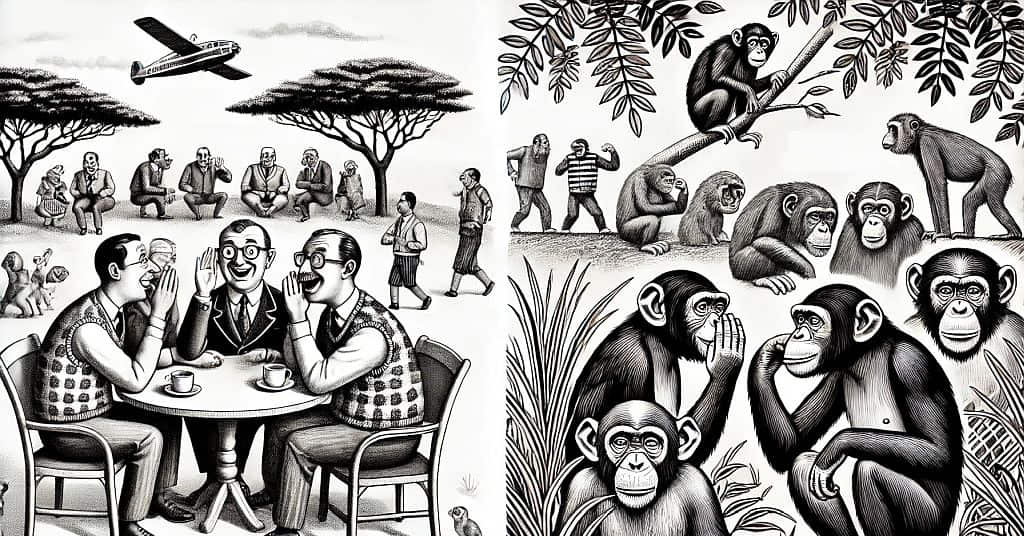

Triadic awareness and Machiavellian intelligence are not unique to humans.

Triadic awareness and Machiavellian intelligence are not unique to humans.

Deception in Primates #

If we see gossip as an evolutionary necessity (survival, optimal allocation of resources), could we hope to find anything akin to gossip, or the rudiments of it in other collaborative species, like ants and bees? #

The concept of gossip as an evolutionary necessity among humans is rooted in our complex social structures, where managing relationships, reputation, and the flow of information has been critical for survival and cooperation. If we extend this line of reasoning to other collaborative species, such as ants and bees, we must first reconsider what “gossip” really entails: communication about others, often in a social context, which influences group behavior or resource allocation based on shared information.

Defining Gossip in Non-Human Terms

In human societies, gossip functions to regulate social bonds, manage reputations, and guide decisions about alliances and cooperation. For ants and bees—species that live in highly cooperative, eusocial colonies—there is no equivalent in terms of “spoken” or symbolic language, but there are mechanisms that serve a similar purpose in regulating group behavior and resource allocation.

Communication in Eusocial Insects

Ants and bees do indeed engage in sophisticated communication systems that share certain functional parallels with gossip, though without the cognitive complexity or nuance found in human interactions. These insects rely heavily on chemical signals (pheromones), vibrations, and other cues to convey information about their environment, resources, and the status of the colony.

Ants: Ants communicate primarily through pheromones. When a forager finds food, it leaves a pheromone trail that others follow. While this isn’t “gossip” in the human sense, it’s a form of indirect communication that influences the behavior of other ants, effectively coordinating resource allocation. Furthermore, ants use pheromones to signal danger, recruit others to tasks, and even regulate the hierarchy within the colony. In a sense, ants are sharing information about the external world and responding to it in a socially coordinated way, much like how humans share reputational information to influence group decisions.

Bees: Honeybees famously use the “waggle dance” to inform others in the hive about the location of food. This is a direct and highly structured form of communication, analogous to sharing crucial information within a social network. Additionally, bees regulate the behavior of the colony through pheromones emitted by the queen and workers, which influence everything from foraging patterns to reproductive roles. The way bees collectively decide on new hive locations also involves a form of “voting” where bees communicate and assess the suitability of various potential sites, sharing information in a process that resembles a collective decision-making dynamic.

Social Regulation and Cooperative Behavior

In both ants and bees, social cohesion and cooperative behavior are maintained through continuous streams of information, even if this communication is more mechanical than the nuanced, context-driven nature of human gossip. Importantly, both species exhibit behaviors that regulate social hierarchies, task allocations, and colony-wide responses to environmental challenges—parallels to how human gossip helps manage social dynamics and resource distribution.

Ant and Bee Caste Systems: In both colonies, pheromonal communication plays a critical role in maintaining the structure of the caste system. For example, in some ant species, pheromones regulate which larvae develop into queens and which remain workers, based on colony needs. This could be seen as analogous to the way humans share information to elevate or suppress individuals within social or professional hierarchies.

Collective Decision Making: Like human gossip, which can shape group opinions or decisions (such as who is trustworthy or capable), the decision-making processes in these insects’ colonies are based on shared information that affects group behavior. In bees, for example, scout bees provide differing signals about the suitability of a new hive location, and the colony’s final decision depends on the spread and intensity of these signals.

Evolutionary Function: Adaptive Value of Information Sharing

While ants and bees don’t have the cognitive complexity to “gossip” in the human sense, their communication systems are highly evolved to serve similar adaptive functions. The key purpose of human gossip—enhancing cooperation, building social bonds, and regulating group dynamics—is mirrored in the efficient information-sharing mechanisms of eusocial insects. These systems optimize resource allocation (e.g., food distribution, labor division) and ensure survival through cohesive action, suggesting that the rudiments of what we call “gossip” do exist in the form of adaptive information sharing.

Thus, while ants and bees don’t engage in reputational management or conversation about “others” in the same way humans do, the essential survival function of disseminating information that influences group behavior is present. In this way, their communication systems serve an analogous purpose, optimizing the colony’s functioning and ensuring efficient resource allocation based on shared knowledge.

What about primates other than humans? #

In the case of other primates, especially the great apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans), as well as some species of monkeys, we find a much closer approximation to human gossip—both in the form of complex social communication and the management of reputations. Unlike eusocial insects such as ants and bees, primates possess the cognitive complexity, social intelligence, and flexible communication systems necessary for something that looks much more like “gossip” in the human sense.

Social Intelligence and Primates: A Cognitive Framework for Gossip

The social structures of primates are highly complex and hierarchical, and survival often depends on maintaining alliances, navigating relationships, and knowing who can be trusted or who is a potential threat. This social complexity is thought to have driven the evolution of greater cognitive capacities in primates, including advanced memory, theory of mind (the ability to understand others’ intentions), and the ability to interpret subtle social cues. These capacities lay the groundwork for the kind of reputation-based information sharing that underlies gossip.

Observational Learning and Indirect Communication

In many primate species, individuals are constantly observing the actions of others, often using that information to adjust their own behavior or relationships. This observational learning and indirect communication is a rudimentary form of gossip. Primates “read” the social environment in much the same way humans do, using vocalizations, gestures, facial expressions, and body language to share information about individuals within the group.

Grooming as a Proto-Gossip Behavior

One of the most well-documented behaviors in primates that serves a “social bonding” function similar to gossip is grooming. Grooming has a dual role: it helps maintain cleanliness and hygiene, but more importantly, it serves as a way to establish and reinforce social bonds. In larger groups, it would be inefficient for each individual to maintain close bonds with everyone through grooming alone. Therefore, it’s hypothesized that grooming in primates evolved into more complex forms of social interaction, such as “vocal grooming,” which in humans may have become verbal gossip.

In this framework, gossip might be seen as an efficient verbal extension of grooming. Just as grooming strengthens alliances and trust, gossip allows individuals to manage relationships, share critical information, and bond with others. Among primates, we see the precursors of this in behaviors that combine social intelligence, communication, and the management of group dynamics.

Examples of Gossip-Like Behavior in Primates

Chimpanzees: Chimpanzees have highly complex social groups that are organized around dominance hierarchies, alliances, and competition. Within these groups, individuals are constantly monitoring others to determine who holds power, who is forming alliances, and who might be a threat or a useful ally. There are clear indications that chimpanzees use vocalizations and body language to signal information about others. For example, studies show that chimpanzees are keenly aware of the reputation of others within their group—who is generous, who is aggressive, or who might share food. This could be seen as a precursor to gossip, where information about social behavior spreads within the group and influences future interactions.

One fascinating aspect of chimpanzee behavior is eavesdropping—individuals will observe and monitor social interactions between others and use that information to inform their own actions, such as deciding whom to form alliances with. This suggests that chimpanzees are sharing and processing information about third parties in ways that mirror human gossip about reputations.

Bonobos: Bonobos, often regarded as our closest relatives, have an even more socially cooperative and peaceable structure compared to chimpanzees. Like chimpanzees, bonobos use grooming and sexual behavior to form bonds and reinforce social ties, but they also rely heavily on vocalizations to coordinate group behavior and relationships. Bonobos are highly sensitive to social dynamics, often mediating conflicts or forming coalitions based on their observations of others’ behaviors. This behavior is akin to gossip in that it involves using indirect information (i.e., social observations) to manage relationships and hierarchies within the group.

Capuchin Monkeys: Among capuchins, a highly intelligent species of New World monkeys, there is evidence of complex social maneuvering, including the management of alliances and competition for resources. Capuchins are known to form coalitions and practice social behaviors that regulate who is allowed access to resources or mates. In some studies, it has been observed that capuchins will change their behavior towards others based on how they are treated by third parties, implying that they are using information about interactions between other individuals to shape their own behavior. This behavior parallels the function of gossip in managing social relationships and power dynamics.

Macaques: In some species of macaques, social hierarchy is especially rigid, and maintaining one’s place in the hierarchy requires constant vigilance. Macaques engage in frequent vocalizations that have been shown to communicate information about status, group movements, and relationships. Among Japanese macaques, for example, individuals who witness others being mistreated by high-ranking individuals will sometimes shift their alliances, much like humans who hear gossip might avoid someone who is deemed untrustworthy or aggressive. This indirect sharing of social information again mirrors the key functions of human gossip.

Gossip and Social Control

One of the key roles of gossip in human societies is social control—gossip helps regulate behavior by spreading reputational information, allowing groups to enforce norms and punish those who violate them. In many primate societies, we see similar forms of social control, though less linguistically elaborate.

For instance, chimpanzees will often engage in coalitionary aggression, where individuals team up to challenge or overthrow a dominant individual. These coalitions are often built on a complex understanding of others’ relationships, alliances, and reputations. The ability to “gossip” about a dominant individual’s weaknesses or misconduct, even without words, serves the same function: it allows subordinates to coordinate and challenge the status quo. Similarly, punishment behaviors in primates are often targeted at individuals who disrupt group cohesion or violate social norms, with the group’s treatment of those individuals influenced by a form of shared, indirect knowledge about their behavior.

Vocalizations and Language as Gossip Precursors

Many primates use a variety of vocalizations that convey specific meanings, from warnings about predators to calls signaling food discovery or emotional states. While these vocalizations are not gossip in the human sense, they demonstrate the importance of shared information in social dynamics. Among some species of monkeys, such as vervet monkeys, distinct calls are used to indicate different types of predators, and these calls are recognized and responded to by the entire group. Over time, vocal communication in primates has likely become more flexible, leading to the kind of reputation-based “gossip” seen in humans.

Conclusion: The Rudiments of Gossip in Primates

While primates do not engage in gossip as linguistically rich or nuanced as humans, they demonstrate many of the fundamental behaviors that serve similar evolutionary functions. Their social intelligence, ability to track reputations, and capacity to influence group dynamics through indirect communication all hint at the evolutionary roots of gossip. The complex, fluid social structures of primates create environments where sharing information about others—whether through vocalizations, gestures, or behavior—helps manage cooperation, competition, and social bonds, much like gossip does in human societies.

Did any researcher notice, or point to the distinction between “public” and “private” grooming? If so, we could probably trace even higher constructs related to power dynamics and social organization, such as “plotting” and “mutiny”? #

Yes, the distinction between “public” and “private” grooming in primates has indeed been observed by researchers, and this distinction is critical for understanding the deeper implications of primate social behavior, especially when considering complex social strategies such as coalition-building, power dynamics, and even the rudimentary forms of “plotting” or “mutiny.”

Public vs. Private Grooming in Primate Research

Primatologists have long studied grooming as a fundamental component of social bonding in primates. Grooming serves not only hygienic purposes but also plays a critical role in building alliances, establishing social hierarchies, and reinforcing social bonds. The distinction between public and private grooming has been noted in several studies, and it carries significant implications for understanding power dynamics within primate groups.

Public Grooming: Grooming that occurs in the presence of the group, visible to others, often has a performative aspect. It is not just an act of bonding between two individuals but can also signal the strength of alliances or status to the entire group. Public grooming helps reinforce social cohesion and can display loyalty to certain individuals or coalitions. In this sense, it acts as a political tool, publicly displaying who is allied with whom, and can help maintain or challenge dominance hierarchies.

Private Grooming: Grooming that occurs away from the view of the larger group, in more secluded or hidden contexts, can take on a different function. Private grooming often occurs between individuals who may be forming secret alliances or who wish to maintain the bond without drawing attention from dominant individuals or rival coalitions. In this sense, private grooming can be seen as analogous to secret meetings or covert communications in human societies—behavior that facilitates plotting, planning, or the coordination of dissent.

Implications for Social Organization and Power Dynamics

The distinction between public and private grooming has direct parallels to complex human behaviors related to social power, including political maneuvering, plotting, and even mutiny. In primates, grooming serves as a social currency, and the way it is performed—whether publicly or privately—signals different intentions and strategies within the group.

Public Grooming and Power Display

Public grooming is often a display of social alignment or support. In many primate species, such as chimpanzees, high-ranking individuals are frequently groomed by lower-ranking members in public settings, reinforcing their dominance and hierarchical position. This act can be a form of ingratiation or submission. It also serves to broadcast alliances and solidarity, showing the group who is in power and who supports that power.

For example, dominant chimpanzees are often groomed by their subordinates in the presence of others, reinforcing the perception of their strength and influence. Public grooming, therefore, plays a key role in maintaining social order and deterring challenges to the hierarchy. In this sense, it functions similarly to political gestures in human societies, where public displays of loyalty (or dissent) can have profound effects on group dynamics.

Private Grooming as a Tool for Coalition Building

On the other hand, private grooming can be a subtle tool for coalition-building, often occurring between individuals who seek to challenge the current power structure or strengthen covert alliances without drawing attention. Private grooming allows individuals to build relationships outside the scrutiny of dominant members, laying the groundwork for potential political maneuvers or challenges to authority.

In chimpanzee and bonobo groups, for instance, lower-ranking individuals may engage in private grooming sessions with others of similar rank to form coalitions aimed at eventually challenging the dominant individual. These coalitions can later manifest in collective aggression or the strategic withholding of support from a dominant member, resulting in a change in leadership.

Coalition Building and “Mutiny”

The behavior seen in private grooming can be interpreted as the precursor to more sophisticated social behaviors that resemble plotting or mutiny in human terms. For instance, in primates, coalitions formed in private may later publicly assert themselves through collective challenges to authority, much like a political coup in human societies.

Chimpanzees: One of the most well-documented examples of coalition-building and “mutiny” is seen in chimpanzee groups, where subordinates can form alliances to overthrow an alpha male. These coalitions are often formed over time through grooming and other forms of social bonding, frequently away from the gaze of the alpha. Once a strong enough coalition is built, these alliances can challenge the dominant individual’s power through direct aggression or by undermining his influence through social isolation.

Bonobos: In bonobo societies, which are more female-dominated and egalitarian than chimpanzees, grooming still plays a critical role in social strategies. Female bonobos, in particular, engage in private grooming and sexual behaviors that help them form alliances and gain influence over males, subtly shifting power dynamics. While bonobos tend to avoid outright aggression, these covert bonds allow females to control resources and mediate conflicts, which can be seen as a form of political maneuvering.

Research Evidence of Strategic Grooming

Some researchers, such as Frans de Waal, have specifically noted the importance of grooming in the social strategies of primates and how it mirrors the political and social maneuvering in human societies. De Waal’s work on chimpanzees emphasizes the role of grooming in alliance formation, dominance struggles, and conflict resolution. His research has highlighted the strategic use of grooming not just as a bonding mechanism but as a calculated social tool that affects group leadership and power dynamics.

In studies of rhesus macaques, researchers have also observed the strategic use of grooming in managing alliances and power. Grooming is often used to curry favor with more powerful individuals, but when done privately, it can signal more covert social strategies, such as the formation of subversive alliances.

Social Manipulation: A Precursor to “Plotting”

Primates are known to manipulate social situations to their advantage, sometimes engaging in deception or misdirection. This can be considered a rudimentary form of “plotting.” For instance, there are documented cases where chimpanzees will deceive others about the location of food or resources, only revealing the information to select individuals. These behaviors are often aimed at securing alliances and avoiding conflict with more dominant members, and they show a capacity for strategic thinking.

Towards Human-Like Social Constructs

The evolutionary trajectory from primate grooming to human gossip, plotting, and political strategies suggests that these behaviors represent a continuum of increasing social complexity. In this context, grooming evolves into verbal communication (gossip), which is more efficient for managing large social networks. Similarly, coalition-building through private grooming evolves into more explicit forms of plotting and rebellion in human societies.

Grooming in primates—especially the distinction between public and private grooming—can therefore be seen as a precursor to the more abstract and complex social constructs humans use to manage power, relationships, and group dynamics. Just as primates use grooming strategically to navigate alliances and challenge authority, humans use gossip, secrecy, and plotting in much the same way to influence social structures and bring about changes in leadership.

Research into primate behavior, particularly the distinction between public and private grooming, highlights the evolutionary roots of complex social strategies such as plotting and coalition-building. While primates do not engage in mutiny or political scheming in the human sense, their use of grooming as a tool for alliance-building, power consolidation, and social control mirrors the more sophisticated behaviors seen in human societies. The study of these behaviors offers valuable insights into the evolution of social organization, manipulation, and power dynamics across species, underscoring the deep continuity between primate and human social strategies.

Since we got this far in our inference, it would be only logical to examine if the “malicious gossip”, that is, deception is observable in primates? #

Absolutely, exploring the existence of “malicious gossip” or deception within primate societies is a natural progression, particularly given the social complexity and strategic behaviors already observed in these species. While primates do not engage in gossip per se—given the absence of language—there is compelling evidence that they engage in forms of deception, manipulation, and misdirection, behaviors that share functional similarities with what we might describe as “malicious gossip” in human societies.

Deception in Primates: Laying the Groundwork

Deception in primates has been well-documented, especially in species with high levels of social intelligence, such as chimpanzees, bonobos, and certain monkeys like rhesus macaques and capuchins. Deceptive behaviors in primates can be seen as an evolutionary adaptation for navigating complex social structures, particularly when competition for resources, status, and mates is high.

What Constitutes Malicious Gossip in Humans?

In human terms, “malicious gossip” typically refers to the act of sharing false or misleading information with the intent to harm someone’s reputation or manipulate a situation to one’s advantage. It’s an overtly social behavior that relies on indirect communication—often exploiting a third party to achieve social dominance, exclusion, or punishment.

When looking for parallels in primates, we won’t find verbal gossip, but we can examine deceptive behaviors that serve similar strategic purposes—undermining rivals, concealing intentions, and manipulating social alliances for personal gain.

Deceptive Behaviors in Primates

- Feigning Ignorance or Concealing Information

Chimpanzees, in particular, are known to practice deception by withholding information, much like how humans might maliciously gossip by selectively sharing information to gain an advantage.

For instance, there are documented cases where a chimpanzee discovers food but hides its knowledge from others. Frans de Waal and other primatologists have observed chimpanzees walking nonchalantly past food sources, only to return later when no one else is watching. This behavior can be seen as an attempt to deceive the group, ensuring exclusive access to resources. This deception serves a similar function to malicious gossip in humans, where individuals might spread disinformation to manipulate access to opportunities or resources.

Chimpanzees also pretend not to notice the intentions or behaviors of others when it suits their strategy. For example, a subordinate might pretend not to see a dominant male approaching, avoiding a confrontation or using the opportunity to plot with another chimpanzee. This indirect manipulation is functionally analogous to how malicious gossip spreads misinformation or withholds truths to influence social dynamics.

- False Alarm Calls

Several primate species have been observed making false alarm calls—vocalizations that signal danger when none is present. These calls can create confusion or redirect attention, allowing the deceiver to access food or escape a confrontation. This behavior is particularly common in some species of monkeys, such as vervet monkeys and rhesus macaques.

In vervet monkeys, for example, individuals have been known to make false alarm calls about predators to distract others from a food source, thereby allowing the deceiver to monopolize the resource. This manipulation mirrors malicious gossip in that the false signal spreads fear or confusion, redirecting attention to gain a personal advantage. False alarm calls are essentially the “fake news” of the animal world—designed to exploit the information-sharing mechanisms of the group.

- Feigning Social Signals

Primates also engage in deceptive social signaling, particularly in competitive social contexts. Subordinate chimpanzees, for instance, may exaggerate submission gestures to avoid aggression from more dominant individuals or to curry favor. Conversely, they may downplay their displays of strength or alliances in the presence of rivals, deceiving others about their true intentions or social standing.

This behavior is functionally similar to the way malicious gossip operates in human societies, where individuals might use flattery or false information to manipulate social hierarchies. In the same way that a human might spread rumors to undermine a competitor’s status, primates manipulate social signals to navigate dominance hierarchies or avoid conflict.

- Triadic Awareness and Coalition Deception

One of the most sophisticated forms of deception observed in primates involves coalition-building and the strategic use of alliances. In chimpanzees and bonobos, where social alliances are critical for maintaining or challenging dominance, individuals have been observed misleading others about the strength or nature of their alliances.

For example, a lower-ranking chimpanzee might privately groom a more dominant individual to secure an alliance, while publicly feigning neutrality or submission to avoid detection by potential rivals. This deception is particularly sophisticated because it requires an understanding of triadic awareness—the ability to recognize and manipulate the relationships between others. Triadic awareness is the cognitive foundation of behaviors that resemble plotting, where primates use indirect social tactics to undermine rivals or manipulate coalition dynamics.

This kind of deceptive alliance-building mirrors the function of malicious gossip in human societies, where individuals might spread false or misleading information to sow discord within a group or to subtly shift the balance of power without directly confronting rivals.

- Strategic Withholding of Social Support

Another form of deception closely related to “malicious gossip” in human terms is the strategic withholding of social support. In primate societies, grooming and support during conflicts are essential for maintaining alliances and social bonds. However, there are instances where individuals will deliberately withhold support, creating confusion or weakening the position of their rivals.

For example, a chimpanzee might observe a conflict between two individuals and choose not to intervene, despite having a close relationship with one of the parties. This behavior can signal a shift in alliances or create the perception that an individual is no longer favored, thereby influencing group dynamics. In humans, this would be akin to malicious gossip that spreads rumors about weakened alliances or betrayals, thereby undermining an individual’s social standing.

Evolutionary Origins of Deception and Malicious Gossip

The existence of deception in primates strongly suggests that the roots of human malicious gossip lie in our evolutionary past. Both deception and gossip require advanced social cognition, including the ability to track reputations, understand the intentions of others, and manipulate social situations for personal gain.

The behaviors observed in primates, particularly those that involve deception or the manipulation of coalitions, represent the evolutionary precursors of human gossip. While primates do not engage in verbal gossip, their strategic use of information and social alliances serves a similar adaptive function—managing group dynamics, regulating access to resources, and influencing social hierarchies.

Cognitive Preconditions for Malicious Gossip

The behaviors discussed above suggest that primates possess some of the key cognitive abilities required for malicious gossip, including:

Theory of Mind: The ability to understand that others have beliefs, desires, and intentions separate from one’s own. This is crucial for engaging in deception or for manipulating social relationships in strategic ways.

Triadic Awareness: As mentioned earlier, this is the ability to understand not just one-on-one relationships, but the relationships between others in a group. Triadic awareness allows primates to engage in complex social strategies, such as coalition-building or undermining rivals, which are foundational to the spread of reputational information.

Social Memory: To engage in deception or manage alliances, primates need strong social memory—the ability to remember past interactions, alliances, and the behavior of others over time. This allows for the manipulation of relationships based on past behavior, much like how humans rely on memory to engage in gossip.

Machiavellian Intelligence: Deception, like gossip, is often associated with Machiavellian intelligence—the ability to manipulate others for personal gain. In primates, this intelligence manifests in the ability to deceive, strategize, and manage social relationships to maximize individual fitness.

Conclusion: The Evolutionary Continuum of Malicious Gossip

Deception in primates can be seen as an evolutionary precursor to the more complex and abstract behaviors of malicious gossip in human societies. Primates engage in various forms of strategic manipulation, including deception, coalition-building, and social signaling, all of which serve to influence group dynamics and individual status. These behaviors demonstrate that primates are capable of using indirect social strategies to achieve personal gain, much like the way humans use gossip to manipulate reputations and relationships.

The cognitive preconditions for malicious gossip—such as theory of mind, triadic awareness, and Machiavellian intelligence—are clearly present in primates. While they may not engage in gossip as we understand it linguistically, their behaviors reveal a deep evolutionary continuity between human and primate social strategies, particularly in how individuals use deception to navigate complex social landscapes.