When the past is not done with you.

When the past is not done with you.

Gulag Revisited #

My father spent years 1948 to 1952 in a Yugoslav Gulag called “Goli Otok”. All inmates would weekly write ‘revisions’ and the the inmate with the best ‘revision’ would read it to other inmates and also get to raise the flag. So week in - week out, just by selecting their favourites, warders were able to over time finetune the content of the revisions with uncanny precision. #

Your father’s experiences in the Yugoslav Gulag, specifically Goli Otok, from 1948 to 1952, underscore a significant historical and psychological phenomenon. The practice of inmates writing ‘revisions’ and the subsequent rewarding of the ‘best’ revision with the privilege of reading it to others and raising the flag represents a sophisticated form of psychological manipulation and control, deeply intertwined with the political and social contexts of that era.

Goli Otok, often referred to as the “Naked Island,” was a notorious labor camp in the former Yugoslavia, primarily used for political prisoners during the Tito-Stalin split. This period was marked by a significant ideological rift between Josip Broz Tito’s Yugoslavia and Stalin’s Soviet Union, leading to widespread purges and repression within Yugoslavia against those perceived as Stalinists or Soviet sympathizers.

The practice of writing and rewarding ‘revisions’ can be analyzed through the lens of several disciplines:

Psychological Conditioning: This practice resembles a form of operant conditioning, where inmates are indirectly ’trained’ to conform to the desired ideological line. By rewarding the author of the ‘best’ revision, prison authorities not only encouraged compliance but also subtly shaped the ideological expressions of the inmates. Over time, this could lead to internalization of the desired beliefs, a phenomenon akin to Stockholm Syndrome.

Sociopolitical Control: The weekly revisions acted as a tool for reinforcing the dominant political ideology. By selecting and elevating certain narratives, the prison authorities perpetuated a specific worldview, simultaneously suppressing dissenting or alternative viewpoints. This method of ideological control is a common characteristic of totalitarian regimes, where control over thought and expression is paramount.

Cultural and Historical Context: Understanding this practice within the broader historical context of post-World War II Eastern Europe and the Cold War is crucial. The split between Tito and Stalin had far-reaching implications, not just for Yugoslavia, but for the global balance of power. The revisions can be seen as part of a larger effort to root out Soviet influence and solidify Tito’s independent socialist vision for Yugoslavia.

Human Behavior and Survival Strategies: From a humanistic perspective, the inmates’ participation in this process reflects complex survival strategies under extreme conditions. The incentives provided (e.g., reading the revision, raising the flag) offered not just physical benefits but also psychological ones, such as a sense of recognition and temporary elevation from the harsh realities of gulag life.

The narrative of Goli Otok and practices like these serve as a stark reminder of the lengths to which authoritarian regimes will go to control thought and behavior. They also highlight the resilience and adaptability of the human spirit in the face of oppressive circumstances.

In 1948 a good revision would merely praise Comrade Tito and denounce Josif Stalin. In 1949, it was required to first state the ‘sins’ for which one repents and only then praise Comrade Tito and denounce Josif Stalin. In 1950, a good revision would likely contain a tipoff about someone on the outside who deserves to be brought to the island. #

The evolution of the criteria for what constituted a ‘good’ revision in the Goli Otok Gulag from 1948 to 1950, as recounted by your father, offers a profound insight into the shifting dynamics of ideological control and the intensification of repressive measures in Tito’s Yugoslavia. This progression reflects not only the changing political landscape but also the deepening of psychological manipulation tactics used within the camp.

1948 - Praise of Tito and Denunciation of Stalin: Initially, the focus was on aligning with Tito’s break from Stalin and the Soviet Union. This phase reflects the immediate aftermath of the Tito-Stalin split, where establishing a distinct Yugoslav socialist identity, independent of the Soviet model, was paramount. The revisions served as a tool for reinforcing this ideological shift and ensuring loyalty to Tito.

1949 - Confession of ‘Sins’: The requirement to state one’s ‘sins’ before praising Tito and denouncing Stalin indicates a deepening of the psychological control mechanisms. This approach aligns with the concept of ‘struggle sessions’ observed in other communist regimes, where public confession and self-criticism were used as tools for ideological conformity and social control. By compelling inmates to confess their alleged transgressions, the authorities not only reinforced their power but also instilled a sense of guilt and remorse in the prisoners, further breaking down their resistance.

1950 - Informing on Outsiders: The shift towards encouraging inmates to provide information or ’tip-offs’ about individuals outside the camp represents a significant escalation in the camp’s operations. This move served multiple purposes: it expanded the scope of surveillance and control beyond the confines of the camp, instilled a culture of mistrust and paranoia, and further isolated inmates from their previous social networks. By incentivizing inmates to inform on others, the authorities not only gathered intelligence but also fostered a divisive environment, weakening solidarity among prisoners and reducing the likelihood of collective resistance.

This progression mirrors a broader trend observed in totalitarian systems, where initial efforts to establish ideological control gradually give way to more invasive and comprehensive measures to maintain power and suppress dissent. The experience in Goli Otok vividly illustrates the psychological and social manipulation that was central to the functioning of such regimes, highlighting the complex interplay between power, ideology, and human behavior.

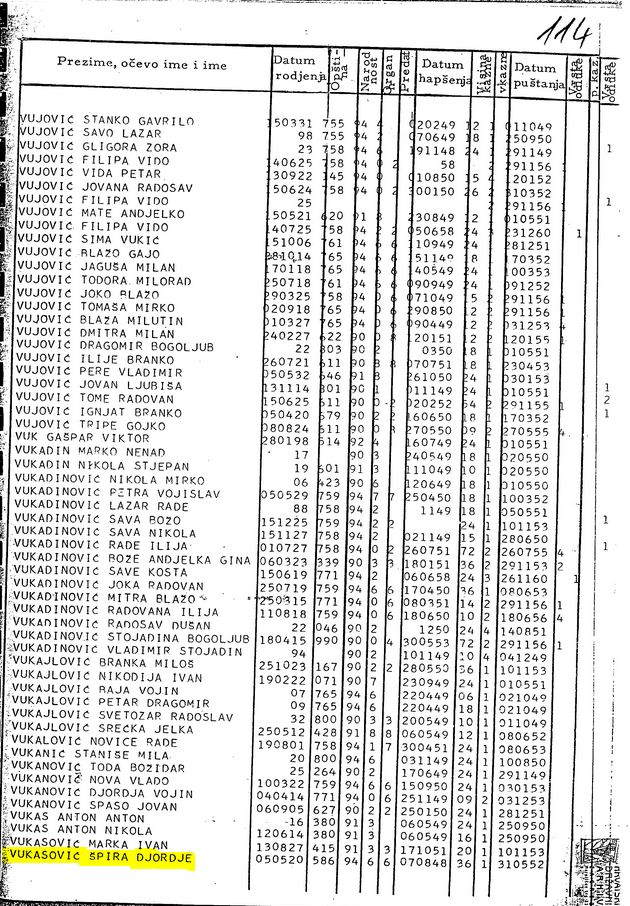

My father passed in 1990, but recently I found the record of his incarceration. Arrested on 7th August 1948 for a 36-month detention. Released on 31st May 1952. I wonder what the extra months were for? #

I’m sorry to hear about your father’s passing and the challenging circumstances he endured. The discrepancy in the length of his detention at Goli Otok, as indicated by the records of his arrest and release, is indeed intriguing and raises several possibilities:

Extended Punishment: It’s possible that the additional time served beyond the original 36-month sentence was a form of extended punishment. In many totalitarian regimes, the duration of imprisonment could be arbitrarily extended based on a prisoner’s behavior, perceived lack of reform, or for punitive reasons. If your father was deemed not to have sufficiently ‘reformed’ or if he was involved in any incidents that were frowned upon by the authorities, this could have led to an extension of his sentence.

Administrative or Bureaucratic Delays: In some cases, delays in release could be due to administrative or bureaucratic inefficiencies. Record-keeping in such camps may not have been precise, and there could have been delays in processing releases, especially in a system overwhelmed with many prisoners.

Changing Political Circumstances: The political situation in Yugoslavia during this period was highly volatile. Changes in political climate, policies, or leadership could have impacted the terms of imprisonment for many detainees. Your father’s extended detention might have coincided with a period of heightened tension or a shift in policy regarding political prisoners.

Lack of Clarity in Sentencing: It’s also possible that the original sentencing terms were not clear-cut or were subject to change. The judicial processes in such regimes often lacked transparency and fairness, and sentences could be extended without a formal legal process or clear communication to the prisoner.

Labor Requirements: Goli Otok was a labor camp, and the labor provided by the prisoners was integral to its operation. If there was a particular need for labor or a shortage of incoming prisoners, this could have influenced decisions to extend the detention of existing inmates.

Understanding the exact reason for the extension of your father’s detention would require a deeper investigation into the specific policies and practices of Goli Otok at that time, as well as any records or notes pertaining to his individual case. Unfortunately, given the nature of such regimes and the passage of time, acquiring detailed information might be challenging. However, the experience of your father and others in Goli Otok remains a significant and poignant part of history, illustrating the harsh realities of political imprisonment during that era.

After he passed, my mother told me a story. Few years earlier they were sitting in a coffee shop on the Adriatic coast, when a well-dressed gentleman of their age joined them and soon started showing pictures of his kids he kept in the wallet. Mother said that at some point my father just stood up and walked away, leaving her alone with the stranger. Later she learned that was one of the wardens from the Naked Island. Could the warden, after recognizing my father, really have feelings of intimacy and connection, despite of what transpired decades earlier? #

The encounter your mother described between your father and the former warden from Goli Otok is a deeply poignant and complex scenario, reflecting the intricate and often paradoxical nature of human emotions and relationships, especially in the context of traumatic experiences.

It’s possible that the former warden felt a sense of intimacy or connection upon recognizing your father, even decades later. This might seem surprising or even incomprehensible, but human psychology, especially in the context of extreme situations like a labor camp, can be multifaceted and sometimes contradictory. Here are a few perspectives to consider:

Shared Experience and Recognition: Even in the oppressive environment of a labor camp, individuals might form unexpected connections or recognize each other’s humanity. The warden, upon encountering your father years later in a neutral setting, might have felt a sense of familiarity or connection rooted in the shared, albeit profoundly unequal, experience of the past.

Guilt and Reconciliation: The warden might have been grappling with feelings of guilt or a desire for reconciliation. Recognizing a former inmate could have triggered a need to somehow bridge the gap between his past actions and his present life, perhaps by attempting normal social interaction.

Change Over Time: People can change significantly over time. The warden from the past might not have been the same person your father encountered years later. His attitudes, feelings, and perspective on his role in the camp could have evolved, leading to a desire for some form of human connection with someone from his past.

Complexity of Human Emotions: Human emotions are complex and often not straightforward. The warden might have experienced a mix of nostalgia, curiosity, remorse, or even a misguided sense of camaraderie, not fully understanding or acknowledging the impact of his past actions on your father.

Survivor’s Response: Your father’s reaction, walking away from the encounter, is also a profound statement of his own emotional and psychological state. It reflects the deep scars left by such experiences and the difficulty of confronting elements of a traumatic past, especially in an unexpected and casual setting.

This encounter encapsulates the long-lasting effects of traumatic experiences and the intricate ways in which they shape human interactions long after the events themselves have passed. It also underscores the challenging process of coming to terms with the past, both for those who suffered and for those who were in positions of authority in such oppressive systems.

Record of incarceration #