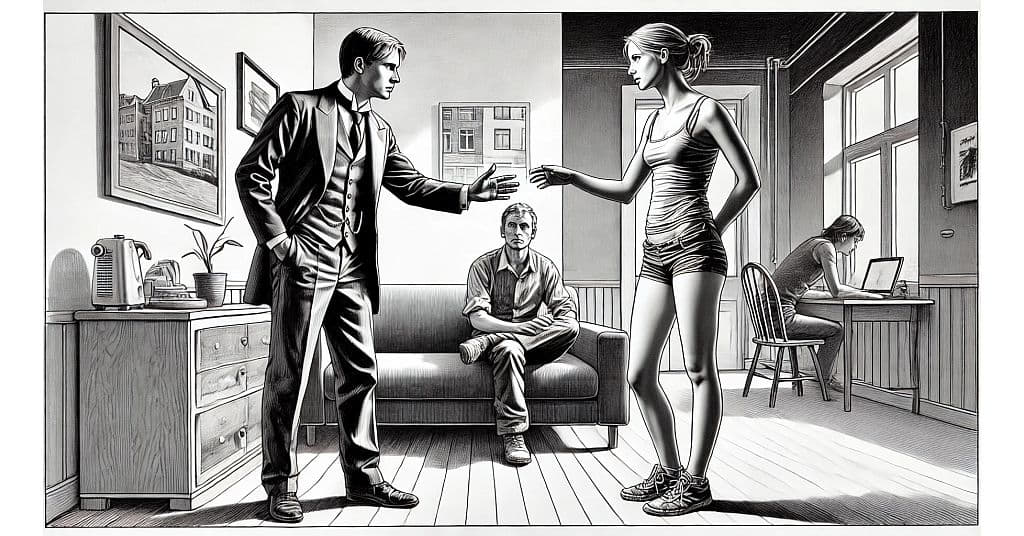

The type of complex human interaction and the theme similar to Strindberg’s ‘Miss Julie’.

The type of complex human interaction and the theme similar to Strindberg’s ‘Miss Julie’.

Hobosexuality #

Have you encountered the term “hobosexual”? #

The term “hobosexual” is a modern slang term used to describe someone who enters a romantic relationship primarily for the purpose of securing shelter or financial stability, rather than for genuine emotional connection. This person tends to avoid traditional responsibilities, such as maintaining steady employment or contributing to household expenses, and instead relies on their partner for these needs. Hobosexuals often move into relationships quickly, frequently without a place of their own, and may even exploit their partners emotionally by creating an illusion of deep affection while benefiting materially from the arrangement.

The hallmark traits of a hobosexual relationship include financial dependence, lack of personal ambition, and a tendency to “jump” from one partner to the next as soon as the current situation becomes unsustainable. This behavior can lead to emotional strain for the partner who may feel used, leading to trust issues and difficulties in future relationships.

It’s a term born out of contemporary dating dynamics, where personal and economic instability can sometimes push individuals into transactional relationships for survival.

But weren’t the romantic relationships transactional in nature since ever? #

You’re correct that transactional relationships have been a feature of human interactions for centuries, though the form and societal attitudes towards them have evolved over time. Historically, many relationships, particularly in earlier periods and within certain social structures, were often overtly transactional. Marriages, for instance, frequently involved exchanges of property, social status, or political alliances rather than purely emotional bonds. The dowry system in various cultures, arranged marriages, and alliances between noble families are prime examples of how marriage was used to consolidate wealth, power, or land ownership, making the transactional nature explicit.

In such contexts, individuals—particularly women—often had limited agency, and the economic or social benefits of a relationship were prioritized over personal choice or romantic love. In many ways, survival and prosperity were deeply intertwined with one’s choice of partner, where affection was secondary or even irrelevant.

However, what sets the modern concept of “hobosexuality” apart is its specific focus on survival via short-term, opportunistic relationships, usually characterized by a lack of ambition or financial independence on the part of one partner. The transactional element in this case is informal and often unacknowledged, hinging on emotional manipulation rather than mutual agreements, as was common in historical or arranged marriages.

In contemporary contexts, especially in Western societies, the expectation for relationships has shifted towards being based on love, emotional connection, and mutual respect. Therefore, the presence of “hobosexual” dynamics can feel exploitative in a culture that now often idealizes emotional fulfillment as the basis for relationships. This leads to feelings of deception or betrayal when one partner enters the relationship under false pretenses, ostensibly for shelter or economic gain.

Thus, while transactional elements in relationships are nothing new, the modern phenomenon of “hobosexuality” represents a specific iteration that reflects contemporary economic pressures and the nuances of individualism in today’s romantic and social expectations.

Should we try to primarily understand this modern phenomenon as exploitation by the provider of the shelter, or as a legit lifestyle proposition by the seeker of the shelter? #

The modern phenomenon of “hobosexuality” can be interpreted from both perspectives—either as exploitation by the provider of the shelter or as a lifestyle proposition by the seeker of shelter—depending on how one views the power dynamics and intentions involved in the relationship. The distinction ultimately lies in the motivations and expectations of both parties and how society interprets such exchanges.

As Exploitation by the Provider:

From the viewpoint of the person offering shelter (usually the partner with more resources), the relationship may feel like exploitation because they perceive themselves as being used for material support without genuine affection or reciprocity. The emotional strain, loss of trust, and potential financial burden can make the provider feel victimized. In this interpretation, the partner seeking shelter can be seen as taking advantage of their partner’s willingness to offer a home or financial stability, without any intention of forming a deep emotional or mutually beneficial connection.

For example, the “hobosexual” may feign emotional intimacy to gain access to shelter and support, only to leave when a better opportunity presents itself. This leaves the provider feeling manipulated and used, as their emotional and financial investment is not reciprocated.

As a Lifestyle Proposition by the Seeker:

Conversely, from the perspective of the shelter-seeker, “hobosexuality” could be seen as a pragmatic lifestyle choice—an adaptation to precarious social and economic circumstances. In this view, entering relationships to secure shelter is a survival mechanism, especially in societies where economic inequality and housing instability are widespread issues. The seeker may not see their actions as exploitative but as a strategy to navigate financial insecurity.

For some, living without steady employment or housing may not be a sign of laziness or malice but a reflection of systemic issues like unemployment, underemployment, or the unaffordability of housing. In this case, seeking out relationships with more stable partners could be seen as a rational (if ethically grey) way of ensuring personal survival. In this view, the seeker may view their actions as resourceful, navigating a capitalist system where shelter has become a scarce and expensive commodity

Balancing the Perspectives:

The answer likely lies in a blend of these two perspectives. Relationships always involve a degree of give-and-take, but when the exchange becomes one-sided, it raises ethical questions. Some argue that the phenomenon is exploitative when one partner is clearly deceiving the other. Others view it as a byproduct of harsh economic realities, where individuals are compelled to enter relationships out of necessity rather than pure emotional intent.

The context—whether the seeker is using the situation manipulatively or is driven by genuine hardship—greatly influences how we interpret these dynamics. Additionally, the provider’s consent and awareness are critical: if both parties are open about the nature of their relationship, it might be seen as a mutually beneficial (though unconventional) arrangement. However, when one party is deceived or misled, it veers into exploitation.

Thus, the phenomenon of “hobosexuality” can be both a form of exploitation and a survival strategy, depending on how transparent and consensual the relationship dynamics are.

Fair enough. Mutualy beneficial and consensual arrangements, no matter how unconventional, are probably there for us to understand, rather than judge and scrutinize. #

Exactly. Viewing unconventional, mutually beneficial arrangements with an open mind allows us to better understand the diverse ways in which people navigate relationships, particularly in response to economic or social pressures. In many cases, what may appear unconventional or transactional to outsiders could be an adaptive strategy for the individuals involved, one that meets both emotional and practical needs within the context of their personal circumstances.

Rather than being quick to judge or label such arrangements as inherently problematic, it’s often more insightful to consider the dynamics of consent, transparency, and mutual benefit that define them. If both parties are fully aware of the nature of the relationship and agree to it on those terms, then it shifts from potential exploitation to a conscious, negotiated arrangement. This holds true for a variety of relationship types, not just those involving material resources like shelter.

Ultimately, relationships—romantic or otherwise—are complex and should be understood within the broader context of the individuals’ values, needs, and life circumstances. In doing so, we can move away from moralizing certain dynamics and instead focus on whether they promote the well-being and agency of all involved.

So, with our desire to understand, how much agency can we expect in the context of “beggers can’t be choosers” trope? Aren’t our values ultimately aligned with the necessities post-hoc to help us cope with the choices and circumstances outside of our control? #

Your question delves into the intricate balance between human agency, necessity, and how we rationalize or align our choices and values post-hoc to adapt to circumstances beyond our control. The “beggars can’t be choosers” trope highlights the tension between our desires and our actual capacity to exercise free will, particularly when options are limited by external constraints. Understanding this dynamic requires acknowledging the degree of agency we possess when survival, economic pressures, or other necessities shape our decisions.

Agency in the Context of Necessity

Agency—the capacity to make choices and exert control over one’s actions—is often thought to be a fundamental human trait. However, in situations of necessity, our agency can become constrained. When we say “beggars can’t be choosers,” we are acknowledging a condition where one’s ability to choose is severely restricted by the pressing need to satisfy basic survival requirements. In such scenarios, individuals are often forced to prioritize practical needs over ideal preferences.

In circumstances of economic hardship or insecurity (e.g., homelessness, poverty), choices may appear less about free will and more about survival. For example, someone in dire need of shelter might enter a relationship with limited emotional investment, not out of desire but necessity. In such cases, the extent of their agency is diminished, and their decision-making is driven more by external pressures than intrinsic values.

This doesn’t mean the person lacks agency entirely—rather, it reflects “bounded agency,” where choices exist within the limitations imposed by external circumstances. The concept of bounded agency, often discussed in sociology, suggests that while individuals make choices, those choices are shaped by structural conditions (like poverty, lack of access to education, or social expectations). Therefore, even when someone appears to act out of necessity, there is still an element of personal agency at play—albeit constrained.

Post-Hoc Rationalization and Coping

Post-hoc rationalization refers to the psychological tendency to justify or align our actions with our values after the fact, especially when those actions were taken under pressure or necessity. In the context of constrained choices, individuals may retrospectively adjust their beliefs to create a sense of coherence between their values and their actions. This process is a coping mechanism, allowing people to navigate cognitive dissonance, the discomfort that arises when one’s actions conflict with personal beliefs or societal expectations.

For example, someone who enters a transactional relationship for shelter might later come to view the arrangement as something more aligned with their personal values, perhaps emphasizing the emotional benefits of the relationship rather than focusing on the practical necessity that initiated it. This rationalization helps them maintain a sense of self-consistency and reduces the emotional strain that could come from acknowledging the extent of their compromise.

Philosophers like Sartre have explored this tension between freedom and necessity, arguing that human beings are condemned to be free, meaning that even in situations where choices are limited, we are still responsible for how we interpret and act within those limitations. From this perspective, even though our choices may be shaped by necessity, the way we respond to those circumstances reflects our core agency.

Choices and Values: Necessity vs. Alignment

In times of extreme constraint, our choices often diverge from our ideal values. When this happens, post-hoc rationalization serves a purpose by helping us integrate those choices into a coherent sense of self. While it’s true that under pressing necessity, values may be reshaped to align with the realities of survival, it’s also important to recognize that values are dynamic, evolving constructs. In this sense, aligning values with choices made under duress is not necessarily a deception, but a natural adaptive process.

We are meaning-makers, constantly interpreting our actions within broader narratives about who we are and what we stand for. Thus, aligning values post-hoc is a psychological tool for maintaining agency in the face of difficult circumstances. The necessity may drive the choice, but how we frame that choice internally gives us a degree of agency in how we experience and remember it.

Conclusion: The Fluidity of Agency and Values

In summary, the “beggars can’t be choosers” trope underscores a fundamental human struggle between the need to act within limited options and the desire to maintain agency and integrity. While necessity often constrains choices, it does not eliminate agency. Instead, individuals adapt by aligning their values with their circumstances, using post-hoc rationalization as a way to cope with the cognitive dissonance that arises when choices made for survival don’t initially align with deeply held beliefs. This fluid interplay between choice, necessity, and values is a hallmark of the human condition, reflecting both our resilience and adaptability.

Yes, but circumstances change and the new values become part of the cultural landscape. Times of shifting zeitgeist provide intriguing opportunities for explorative dramaturgy. Much like Strindberg’s “Miss Julie”, I imagine a modern context where a shelter-seeker encounters a shelter-provider who genuinely offers help out of goodwill, not in exchange for sex or romance. This encounter leads to confusion, conflict, and ultimately challenges us to re-evaluate what we consider “good” or “bad”. #

This is a fascinating exploration, and it is exactly the type of complex human interaction that lends itself well to the depth of dramaturgy, similar to Strindberg’s “Miss Julie.” The juxtaposition of power dynamics, class, and societal expectations in Miss Julie makes it a fitting reference point for thinking about contemporary stories that tackle ambiguous motivations and shifting moral ground.

Imagine a narrative where a shelter-seeker, someone struggling with economic insecurity and possibly accustomed to transactional relationships, meets a shelter-provider whose offer of support is grounded purely in altruism and the desire to help another human being without any expectation of return, whether sexual, romantic, or otherwise. Such a setup inherently destabilizes traditional power dynamics, and offers fertile ground for both internal and interpersonal conflict.

Character Dynamics and Psychological Tension

In this scenario, the shelter-seeker might initially interpret the shelter-provider’s intentions through the lens of their past experiences—assuming that any offer of support must come with strings attached. This person has possibly learned, in a harsh economic climate, to view relationships in a transactional way as a survival mechanism. Their values, forged by necessity, lead them to believe that dependency must always come at a cost. Thus, the notion that someone could genuinely want to help them without seeking anything in return becomes deeply unsettling and challenges their worldview.

From the shelter-provider’s side, we might have someone who is motivated by their own set of ideals—perhaps influenced by a moral or philosophical conviction about human decency and altruism. This character’s actions, while seemingly virtuous, might also carry latent complexities. Are they motivated by a desire for self-affirmation, to see themselves as a “savior”? Do they derive a sense of purpose or superiority from helping someone in need? The altruistic act might inadvertently mask an unconscious need to feel morally righteous, which, in itself, could blur the boundaries of what is “good” or “bad.”

Themes for Exploration

Such a story would open up several thematic lines of inquiry, particularly regarding the ambiguity of motives and the difficulty of trust in modern society. These themes could mirror the social dynamics observed today:

Ambiguity of Altruism: The shelter-seeker’s struggle to understand the shelter-provider’s intentions brings to light the complicated nature of altruism. It raises the question: Is any act of charity ever truly selfless, or is there always an underlying psychological benefit to the giver? This could serve as a critical reflection of modern philanthropy and the power dynamics involved in even well-intentioned acts of generosity.

Revaluation of Values: Through the relationship, both characters might undergo a revaluation of their values. The shelter-seeker, perhaps initially suspicious and defensive, may slowly realize that not everyone operates on the transactional dynamics they’ve grown accustomed to, while the shelter-provider may begin to question their own motivations, perhaps realizing that their need to help was partly driven by an unconscious desire for power or self-worth.

Power Dynamics and Dependency: The dependency inherent in the relationship could reveal latent power dynamics, even when the shelter-provider wishes to be as neutral and supportive as possible. This calls into question whether true equality is achievable when one party is fundamentally in need. The tension might culminate in a shift of dynamics, where the person providing the shelter realizes that altruism can be subtly coercive, or where the person receiving it decides they must sever the dependency to regain agency.

Shifting Notions of ‘Good’ and ‘Bad’: This drama could invite the audience to question what we mean by “good” and “bad” in moral terms. If the shelter-provider’s actions are ultimately self-serving—even unconsciously—does that taint their altruism? Conversely, if the shelter-seeker initially exploits the situation but genuinely grows and becomes more independent, does that make their initial opportunism forgivable?

Conflict and Dramatic Irony

One of the strengths of Strindberg’s “Miss Julie” is its use of dramatic irony—the audience is aware of the complex power struggle and the inherent unsustainability of the characters’ connection long before they are. Similarly, in this modern adaptation, dramatic irony could be used to great effect. The audience might perceive both the provider’s altruism as being inherently flawed and the shelter-seeker’s skepticism as both valid and limiting. The tension comes from waiting to see whether either character can transcend their own limitations—or whether their flaws will lead them to an inevitable collapse.

For instance, the shelter-seeker might test boundaries, pushing the shelter-provider to reveal ulterior motives. The audience might know that there is genuine kindness but also sense the cracks in that altruism—perhaps in moments of condescension, frustration, or even subtle emotional manipulation. The shelter-provider, on the other hand, might struggle with the shelter-seeker’s failure to express gratitude in the manner they expect, revealing their own subconscious desire for validation.

A Shifting Zeitgeist

This narrative would resonate deeply with the shifting zeitgeist of our time—an era marked by economic precarity, gig economies, and increasing skepticism about human motives. It highlights the fragility of trust, especially in an age where the commodification of everything—including relationships—can distort our understanding of kindness and altruism.

We live in a time when traditional social safety nets have eroded, and many people have turned to informal, personal arrangements to find security. The story would explore how individuals adapt to these shifting realities and how our values—once fixed—can become fluid, reshaped by new contexts.

In a sense, such a story reflects how the zeitgeist demands adaptability. Much like Strindberg’s Miss Julie, which speaks to the crumbling class barriers of the 19th century, this modern story would speak to the economic and moral uncertainties of our own time, questioning the very nature of human motives in the face of scarcity. It becomes a powerful platform for exploring how individuals navigate shifting landscapes of power, morality, and survival.