Deep evolutionary roots, while recognizing the significant influence of cultural factors.

Deep evolutionary roots, while recognizing the significant influence of cultural factors.

Instincts in Social Life #

In an otherwise inconsequential movie “Election” (1999) three students stood for a high school election. One of them, privately, in the voting booth, questioned if it was ethical to vote for oneself and decided to cast his anonymous vote for one of the opponents. Let us analyse this choice. #

The scenario described in “Election” (1999) provides a fascinating opportunity to delve into the ethics of self-voting, a concept that can be analyzed through various lenses such as ethical theory, psychological behavior, and democratic principles. Let us explore the implications and reasoning behind the student’s decision to vote for an opponent instead of himself.

Ethical Analysis #

- Utilitarian Perspective:

From a utilitarian standpoint, the morality of an action is determined by its consequences, aiming to maximize overall happiness and well-being. Voting for oneself could be seen as a selfish act that primarily benefits the individual candidate. However, if the student genuinely believes that the opponent is a better choice for the collective good of the school community, then voting for the opponent can be considered ethical as it promotes the greater good.

- Deontological Perspective:

Deontological ethics focuses on the adherence to rules, duties, and obligations rather than the consequences. If the student believes that there is an ethical duty to act impartially or to avoid self-interest in voting, then voting for the opponent aligns with this moral duty. This perspective emphasizes the integrity of the voting process and the responsibility to prioritize the common good over personal gain.

Psychological Behavior #

- Self-Esteem and Identity:

The decision to not vote for oneself might stem from a complex interplay of self-esteem and personal identity. The student may possess a high level of self-awareness and humility, recognizing personal limitations and acknowledging the potential strengths of the opponent. This act of voting against oneself can be seen as a demonstration of confidence in the democratic process and an honest appraisal of one’s capabilities.

- Social Influences and Peer Pressure:

High school environments are often fraught with social dynamics and peer pressures. The student’s decision could be influenced by a desire to be perceived favorably by peers, teachers, or the broader school community. This action might be seen as a way to avoid appearing arrogant or overly self-confident, thus maintaining social harmony and relationships.

Democratic Principles #

- Fairness and Impartiality:

The concept of fairness is central to democratic principles. By voting for an opponent, the student may be striving to uphold the fairness of the election process. This act can be interpreted as an attempt to avoid the potential bias of self-voting and to ensure that the outcome of the election truly reflects the preferences of the majority.

- Representation and Legitimacy:

In democratic elections, candidates are expected to represent the interests of their constituents. By voting for an opponent, the student acknowledges that the best representative might not always be oneself. This decision can enhance the legitimacy of the elected candidate, as it reflects a genuine choice made by someone who prioritizes the collective interest over personal ambition.

The student’s decision to vote for an opponent instead of himself raises important ethical questions and highlights the complexity of individual behavior in democratic processes. By analyzing this choice through various ethical theories, psychological perspectives, and democratic principles, we gain a deeper understanding of the nuanced motivations behind such actions. This decision, while seemingly counterintuitive, can be seen as a testament to the student’s commitment to integrity, fairness, and the greater good of the community.

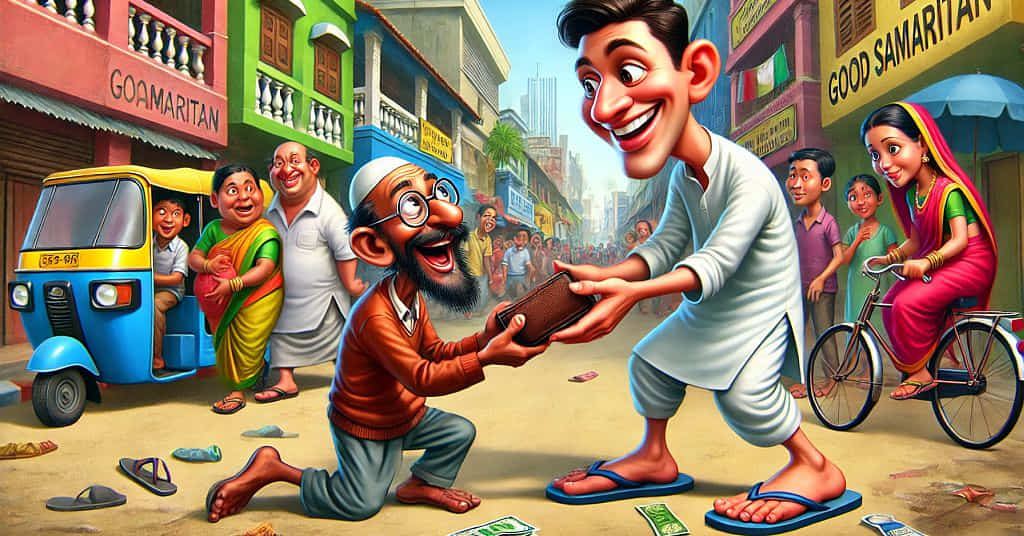

I remember reading a study on Good Samaritans - apparently, after employing their cognitive capacity in a delayed interview, most agreed that their kind act was a silly thing to do. #

The scenario you describe about Good Samaritans reassessing their actions as “silly” after cognitive reflection is a rich area for analysis, touching on psychological, ethical, and cognitive dimensions. This phenomenon can be examined through several lenses: the psychology of decision-making, the role of cognitive dissonance, and the ethics of altruism.

Psychological Perspective #

- Immediate vs. Delayed Reflection:

When individuals perform a kind act, their decision is often driven by immediate emotional and moral impulses. These impulses can include empathy, a sense of duty, or the desire to help others. However, when given time to reflect, individuals engage their cognitive capacities more deeply, often re-evaluating their actions based on practical considerations, personal costs, or social norms. This shift from an emotional to a rational evaluation can lead to a reassessment of their actions as “silly” or impractical.

- Cognitive Dissonance:

Cognitive dissonance theory, proposed by Leon Festinger, suggests that individuals experience discomfort when they hold conflicting beliefs or engage in behavior that contradicts their self-concept. After performing a Good Samaritan act, individuals might experience dissonance if they perceive their actions as inconsistent with their self-image as rational decision-makers. To reduce this dissonance, they might rationalize their behavior as “silly,” aligning their self-perception with the belief that such acts are impractical or irrational.

Ethical Perspective #

- Altruism vs. Self-Interest:

Ethically, altruistic actions are often seen as morally commendable because they prioritize the well-being of others over self-interest. However, when individuals reflect on their actions, they might use a utilitarian framework, assessing the consequences and costs of their behavior. This rational assessment can lead to a perception that their altruistic act was not the most effective or beneficial use of their resources, hence deeming it “silly.”

- Moral Intuition vs. Moral Reasoning:

Moral intuition involves immediate, automatic moral judgments, whereas moral reasoning involves deliberate, controlled thought processes. Good Samaritan acts are typically driven by moral intuition, which is why they might feel natural and right in the moment. Upon reflection, moral reasoning can dominate, leading individuals to critique their actions based on broader ethical principles or societal norms, which might not always favor spontaneous acts of kindness.

Cognitive Perspective #

- Heuristic Processing:

In the moment, individuals often rely on heuristics—mental shortcuts that facilitate quick decision-making. Helping someone in need can be seen as a heuristic response rooted in social and evolutionary imperatives. During delayed reflection, however, individuals engage in more analytical thinking, which can highlight the downsides or impracticalities of their actions, leading to a perception of foolishness.

- Temporal Discounting:

Temporal discounting refers to the tendency to devalue rewards or consequences that occur in the future compared to those in the present. Immediately after the act, the positive emotional reward is salient. Over time, as the emotional impact fades, individuals may discount the value of their good deed, perceiving it as less significant or worthwhile, which could lead to the judgment of it being “silly.”

Implications and Conclusion #

This phenomenon highlights the complex interplay between emotion and cognition in ethical decision-making. While immediate responses often align with deeply ingrained moral instincts, delayed cognitive reflection can introduce practical and rational considerations that might undermine the perceived value of altruistic acts. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for comprehending human behavior in moral contexts and can inform approaches to fostering and sustaining altruism in society.

By analyzing the reassessment of Good Samaritan acts through these perspectives, we gain a deeper appreciation for the psychological and ethical factors that influence our judgments of right and wrong. This understanding can help in designing interventions and educational programs that reinforce the value of altruism, even when delayed cognitive reflection might suggest otherwise.

Well, in these two scenarios, we gave one credit to intuition and one to reason - something’s gotta give. Or this all is a fuzzy area? #

The tension between intuition and reason in ethical decision-making is indeed a complex and often “fuzzy” area. Both intuition and reason play crucial roles in how we make moral choices, and they can sometimes lead to conflicting conclusions. Understanding this interplay requires an exploration of their respective strengths, limitations, and how they interact in different contexts.

Intuition vs. Reason: Strengths and Limitations #

- Intuition:

Strengths:

Speed and Efficiency: Intuitive judgments are rapid and require minimal cognitive resources, making them highly effective in situations requiring immediate action.

Emotional Resonance: Intuition often aligns with our emotional responses, providing a sense of moral certainty and motivating pro-social behavior.

Evolutionary Basis: Many intuitive responses are deeply rooted in our evolutionary history, designed to promote survival and social cohesion.

Limitations:

Bias and Heuristics: Intuitive judgments can be prone to cognitive biases and heuristics, leading to systematic errors or prejudiced outcomes.

Lack of Justification: Intuitive decisions are often difficult to articulate and justify, making them vulnerable to scrutiny and skepticism.

Context Dependence: Intuition may be influenced by immediate context and emotions, which can lead to inconsistency and variability in moral judgments.

- Reason:

Strengths:

Deliberation and Analysis: Reason allows for careful consideration of evidence, consequences, and principles, leading to more informed and consistent decisions.

Justifiability: Reasoned judgments can be articulated and defended with logical arguments, enhancing their credibility and acceptance.

Long-term Perspective: Reason enables consideration of long-term consequences and broader ethical principles, potentially leading to more sustainable and fair outcomes.

Limitations:

Cognitive Load: Reasoning requires significant cognitive effort and time, which can be impractical in urgent situations.

Emotional Detachment: Excessive reliance on reason can lead to moral disengagement or cold, calculating decisions that lack empathy and human connection.

Paralysis by Analysis: Overthinking can lead to indecision or delayed action, undermining timely and effective responses.

Integrating Intuition and Reason #

Given their respective strengths and limitations, a more nuanced understanding recognizes that intuition and reason are not mutually exclusive but complementary aspects of moral decision-making. Effective moral reasoning often involves an interplay between intuitive and rational processes, each informing and tempering the other.

- Dual-Process Theories:

Dual-process theories in psychology suggest that human cognition operates through two systems:

System 1: Fast, automatic, and intuitive.

System 2: Slow, deliberate, and rational.

In moral decision-making, initial intuitive responses (System 1) can be followed by reflective reasoning (System 2), allowing individuals to refine and, if necessary, revise their judgments. This iterative process leverages the strengths of both systems, balancing immediate emotional responses with careful analysis.

- Contextual Sensitivity:

The appropriate balance between intuition and reason can vary depending on the context. In high-stakes, complex situations, greater reliance on reason may be necessary to navigate the intricacies and potential consequences. Conversely, in familiar, everyday scenarios, intuitive judgments may be more efficient and equally effective.

- Moral Education and Development:

Moral education can play a crucial role in enhancing the interplay between intuition and reason. By cultivating moral virtues, empathy, and critical thinking skills, individuals can develop more reliable and well-rounded moral instincts and reasoning abilities. This holistic approach fosters moral maturity and the capacity to navigate ethical dilemmas with greater insight and balance.

The interplay between intuition and reason in moral decision-making is inherently complex and context-dependent. Recognizing the complementary nature of these cognitive processes allows for a more sophisticated and flexible approach to ethical dilemmas. While intuition provides the immediacy and emotional depth necessary for moral action, reason offers the deliberation and justification required for moral clarity and consistency. Embracing this dynamic interplay enables a more resilient and adaptive moral framework, capable of addressing the diverse and evolving challenges of human life.

I wonder what Dario Maestripieri would say about the role of our instincts while relating to each other? #

Dario Maestripieri, a renowned primatologist and expert in behavioral biology, has extensively studied the role of instincts and their influence on human behavior, particularly in social contexts. Drawing from his research and perspectives, we can infer several insights about the role of instincts in our interactions with one another.

Evolutionary Basis of Social Behavior #

Maestripieri’s work often emphasizes the evolutionary roots of human behavior. He argues that many of our social instincts are inherited from our primate ancestors and are deeply embedded in our biology. These instincts have evolved to enhance survival and reproductive success in social groups.

- Social Hierarchies:

Human social interactions are often influenced by hierarchical structures, a trait we share with many primate species. Our instincts drive us to navigate these hierarchies, seeking status and recognition while avoiding conflict with higher-ranking individuals. This instinctual behavior ensures social cohesion and stability within groups.

- Cooperation and Reciprocity:

Instincts related to cooperation and reciprocity are fundamental to human social life. These behaviors have evolutionary advantages, as they facilitate mutual aid and support, increasing the chances of survival for individuals within a group. Maestripieri would likely highlight that our instinctual drive to reciprocate favors and cooperate with others is a cornerstone of social bonding and collective action.

Instincts and Emotional Responses #

Our instincts significantly shape our emotional responses, which in turn influence our social interactions. Maestripieri’s research into primate behavior sheds light on the parallels between human and primate emotional reactions.

- Empathy and Altruism:

Empathy, the ability to understand and share the feelings of others, is a powerful instinctual response that promotes altruistic behavior. Maestripieri might argue that empathy is rooted in our evolutionary history, where the survival of the group depended on individuals caring for one another. This instinct drives us to help others in distress and form deep emotional connections.

- Aggression and Conflict Resolution:

Aggression is another instinctual response that has evolutionary roots, primarily as a means of protecting resources and ensuring survival. However, humans, like many primates, also have instinctual mechanisms for conflict resolution, such as reconciliation behaviors. Maestripieri’s insights suggest that while aggression can disrupt social harmony, our instincts also equip us with strategies to mend relationships and restore peace.

Cultural Modulation of Instincts #

Maestripieri would likely acknowledge that while our instincts play a crucial role in social behavior, culture significantly modulates these instincts. Human societies have developed complex cultural norms and values that shape and sometimes override instinctual responses.

- Social Norms and Morality:

Cultural norms influence how we express and regulate our instincts. For instance, while our instincts might drive us to seek status, cultural norms dictate acceptable ways of achieving and displaying it. Maestripieri would point out that morality and ethical behavior, although rooted in basic instincts like empathy and fairness, are refined and expanded through cultural evolution.

- Learning and Adaptation:

Humans are highly adaptable, and our social instincts are flexible. Through learning and socialization, we can modify our instinctual behaviors to fit the demands of different social environments. Maestripieri’s research underscores the importance of this adaptability in navigating the complexities of modern human societies.

Dario Maestripieri’s perspective on the role of instincts in social interactions highlights the deep evolutionary roots of our social behavior while recognizing the significant influence of cultural factors. Our instincts provide the foundation for social hierarchies, cooperation, empathy, and conflict resolution, but culture and learning shape these instincts into the complex social behaviors observed in human societies today. By understanding the interplay between our biological instincts and cultural influences, we gain a richer appreciation of the factors that drive our social interactions and relationships.