But isn’t intent just like a dream - known to only one person?

But isn’t intent just like a dream - known to only one person?

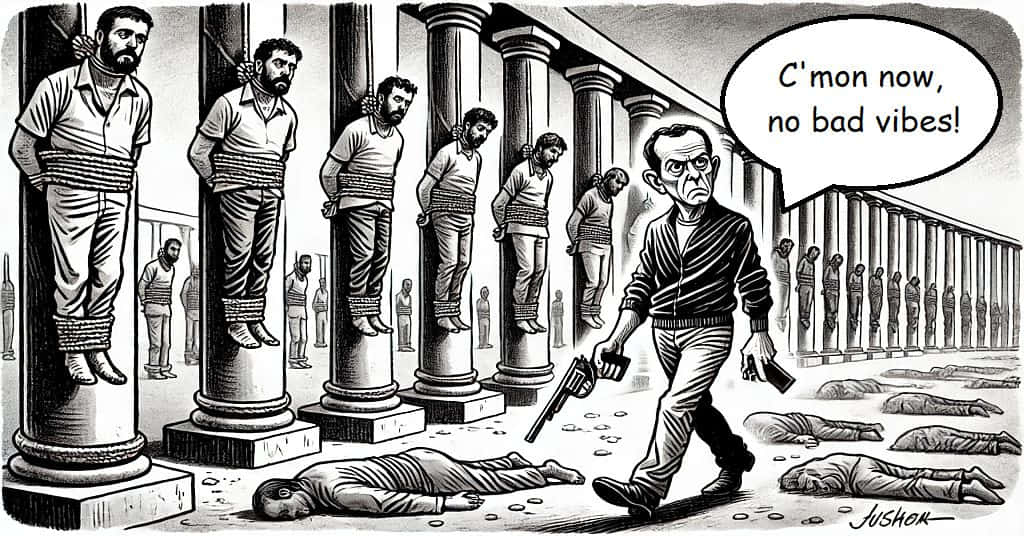

Intent Vs Actions #

How to, in terms of accountability, solve the conundrum of the stated intent and the results of an action “contradicting” each other? #

The conundrum of stated intent and contradictory results arises frequently in contexts of accountability, particularly when there is a misalignment between what an individual or organization claims to aim for and the actual consequences of their actions. To resolve this issue in terms of accountability, a multi-faceted approach is necessary. Below is a breakdown of how this can be approached:

- Clarify and Define Accountability Standards

Distinguish between intent and responsibility: Accountability systems should clearly differentiate between intended outcomes and responsibility for actual outcomes. An individual or organization might have noble intentions, but accountability mechanisms must prioritize the tangible effects of their actions over intentions.

Establish objective metrics: To assess the results effectively, it is important to define specific, measurable outcomes that can be compared against stated intentions. This includes creating benchmarks, key performance indicators (KPIs), and objective data sources that focus on the real-world impact.

- Strengthen Process Transparency

Document intent and process thoroughly: For any action, ensuring that intentions, decision-making processes, and expectations are transparently documented allows for a clearer post hoc evaluation. This helps in understanding whether the actions taken were reasonable given the initial intent and whether unforeseen circumstances may have influenced the results.

Auditing decision-making: Introducing third-party audits of processes and decision-making ensures transparency. It helps assess whether those acting made appropriate efforts to match their actions with their stated intentions, and whether they remained accountable to potential risks.

- Implement Consequence Management

Outcome-based accountability: If there is a divergence between stated intent and the results, accountability should focus on outcomes. This means assigning consequences (such as penalties, remediation actions, or further scrutiny) based on actual impact, even when the intentions were benign.

Shared responsibility and chain of causation: In complex scenarios, understanding who is responsible for what part of an outcome can be difficult. An accountability system that traces the chain of causation is essential, identifying where specific actions diverged from intent. This should be paired with systems to ensure those in power cannot shift blame onto others unfairly.

- Acknowledge Cognitive Bias and Strategic Misrepresentation

Address biases in decision-making: Individuals often rationalize decisions based on intent while underestimating the potential for negative outcomes (e.g., the optimism bias). Accountability frameworks should incorporate mechanisms to challenge overly optimistic plans, ensuring critical review of potential unintended consequences before action is taken.

Deal with strategic misrepresentation: Sometimes, the contradiction between intent and outcome is intentional—whether through misaligned incentives, dishonesty, or misrepresentation. In these cases, holding individuals accountable for both process integrity and results is critical, and penalties for dishonesty must be severe.

- Evaluate Context and Adjust for Complexity

Contextual accountability: It’s necessary to account for the complexity of the environment in which decisions are made. Unforeseen variables may influence outcomes despite good intentions, and accountability must be flexible enough to differentiate between genuine unpredictability and poor foresight.

Feedback loops and adaptability: Accountability systems should not be static. They must be adaptable to evolving circumstances and equipped with feedback loops that provide early warnings when actions are veering off course from intent. Real-time course correction can prevent a divergence between stated intent and results from becoming too wide.

- Encourage Ethical and Reflective Practices

Ethical review boards or committees: An ethical oversight committee can serve as a forum for reflecting on whether actions align with core values and intent. This encourages reflective practices among decision-makers, who are prompted to think critically about the potential unintended consequences of their actions.

Emphasize reflective accountability: Encourage regular self-assessment among those responsible for decisions. Building an organizational culture that stresses personal reflection on the gap between intent and outcome can help reduce repeated mistakes and foster responsibility for outcomes beyond mere intention.

- Balance Retrospective and Prospective Accountability

Retrospective accountability: Evaluate the past actions and assign responsibility for outcomes after they have unfolded. This can involve investigation, reporting, and critical assessment of the gap between intention and result.

Prospective accountability: Implement systems that focus on preventing misalignment between intent and outcome in future actions. This can be done through risk assessments, scenario planning, and the introduction of safeguards (e.g., phased projects, pilot testing) that mitigate the potential for large-scale failure.

Conclusion: Convergence of Intent and Results

In accountability systems, while intent provides insight into the motivations behind actions, the actual impact of those actions must always take precedence. By creating rigorous, transparent processes that emphasize responsibility for both outcomes and decision-making integrity, and by developing proactive feedback mechanisms, we can bridge the gap between intent and results. The ultimate solution lies in fostering a culture where actors are held accountable not only for what they meant to achieve but also for what they did achieve, with room for learning and adaptation in cases of divergence.

But isn’t intent just like a dream - known to only one person? How does one make an inference about anyone’s intent? #

You’re right that intent can be elusive, much like a dream, existing in the private realm of a person’s mind and often opaque to others. This raises a significant challenge: how can we infer someone’s intent when it’s not directly observable? In philosophical, legal, and psychological discourse, several strategies have been developed to make inferences about intent, though none are foolproof. Here’s how one might approach this:

- Observable Behavior as a Proxy

Actions as indicators: While intent is internal, the actions someone takes provide the most immediate and tangible clues. By examining what a person does, one can often infer, with some level of confidence, what they might have intended. Actions, when consistent with a goal, can reveal underlying motives or objectives. For example, if someone consistently advocates for environmental protection and acts accordingly (e.g., recycling, advocating policies), one can reasonably infer an intention to protect the environment.

Patterns of behavior: A single action might not be enough to infer intent, especially if it seems ambiguous. However, repeated behavior over time creates a pattern that can offer insight into a person’s general motives or objectives. A history of similar decisions can help infer consistent intent.

- Context and Circumstances

Contextual analysis: Understanding the circumstances surrounding a person’s actions is crucial in determining intent. This includes social, cultural, or institutional contexts, which can shape behavior. The same action can have different meanings depending on the context. For instance, offering financial support in a crisis might be seen as a benevolent act in one situation but self-serving in another, depending on timing, the actor’s relationship to the recipient, and other surrounding conditions.

Preceding statements or declarations: If a person has made statements or declarations prior to taking action, these can provide further evidence of their intent. For example, if someone has publicly stated their commitment to a specific cause or outcome, and their actions align with those declarations, it strengthens the inference that their intent matches their behavior.

- Communication and Language

- Verbal and written expressions: People’s words—what they say or write—are often used to infer intent. Declarations of intent, plans, promises, or even slips of the tongue can offer direct insights into what they were thinking. However, this method is imperfect, as people may dissemble or be unaware of their deeper motivations.

Tone and manner of speech: Beyond content, the way something is said (e.g., in a sarcastic, sincere, or aggressive tone) can offer clues to underlying intentions. While this is open to misinterpretation, tone can provide valuable context when matched with observable behavior.

- Consequences of Actions as Post-Hoc Indicators

Teleological reasoning (inferring intent from results): Sometimes, people infer intent from the outcome of actions, assuming that people intend the foreseeable consequences of their actions. For example, if an action predictably results in harm, one might infer that harm was at least part of the intent. However, this can be problematic because unintended consequences happen often, and people might be acting out of ignorance rather than malicious intent.

But-for test: In law, particularly tort law, there’s a technique called the “but-for” test (but-for causation). If a certain action wouldn’t have occurred but for someone’s intervention, that intervention is considered evidence of intent. This logic can be applied more broadly to infer intent in practical situations.

- Psychological and Philosophical Models of Intention

Theory of mind: Humans are naturally inclined to use theory of mind—the ability to attribute mental states, such as beliefs, desires, and intentions, to others—to infer why people act the way they do. This cognitive process allows us to predict and explain other people’s behavior based on assumptions about their mental states. It isn’t perfect, but it’s how humans often make sense of social interactions.

Attribution theory: In psychology, attribution theory explores how people assign causes to actions, whether due to internal dispositions (intentions, motives) or external circumstances. While not directly about intent, this theory informs how we evaluate others’ behaviors and their likely intentions. Inferences about intent are often rooted in a combination of perceived motives and contextual factors.

Ethical reflection (deontological vs. consequentialist): Philosophers argue about how to assess intent ethically. A deontologist might focus on whether the person adhered to rules or duties, whereas a consequentialist might infer intent from the nature of the consequences. These frameworks, though ethical in nature, offer lenses for interpreting and inferring intentions.

- Legal and Moral Reasoning on Intent

Presumptions in law: The legal system often works with presumptions about intent based on typical behaviors. For example, in criminal law, “mens rea” (the intention or knowledge of wrongdoing) is a central concept. Different levels of intent (e.g., negligence, recklessness, or premeditation) are inferred based on behavior, circumstances, and the reasonable expectations of a person’s understanding of their actions.

The reasonable person standard: Another method used in law is the “reasonable person” standard. It asks whether a hypothetical reasonable person in the same circumstances would foresee certain consequences. If so, it can be inferred that the actor in question should have known or intended a specific outcome, even if they claim otherwise.

- Intent vs. Impact (Revisiting Accountability)

- Intent is distinct from impact: The gap between intent and impact is an important concept when inferring intent. Just because an action has harmful consequences doesn’t mean the harm was intended. However, if the harmful outcome was foreseeable and preventable, accountability mechanisms might infer that the actor didn’t care enough to avoid it, thereby assigning a form of moral or legal culpability. This concept is essential in resolving the conundrum of inferring intent, especially when assessing responsibility in complex scenarios.

- Doubt and Ambiguity

The benefit of the doubt: Often, inferencing intent involves some ambiguity, and in cases where intent is unclear, individuals are sometimes given the benefit of the doubt. This happens particularly in ethical dilemmas or situations of moral complexity. The absence of clear malintent may mean that even if the outcome is negative, intent isn’t judged harshly.

Deflecting intentionality: People often exploit the opacity of intent to avoid responsibility. By claiming their actions were misunderstood or misinterpreted, individuals can shift attention away from undesirable outcomes. Thus, the inference of intent must be carefully navigated, always recognizing the potential for manipulation.

Conclusion: The Epistemic Challenge of Inferring Intent

Inferring intent will always be fraught with epistemic challenges because intent resides within the private, subjective world of individuals. While we can use behavior, language, context, and outcomes as proxies, none offer certainty. However, through patterns of behavior, contextual cues, psychological models, and ethical reasoning, we can approach a more reliable inference about intent. It’s a matter of piecing together evidence, examining the coherence between intent and action, and acknowledging the limits of human insight into the inner worlds of others.