Perception of beauty in art can trigger the release of dopamine in the orbitofrontal cortex.

Perception of beauty in art can trigger the release of dopamine in the orbitofrontal cortex.

Paint Job #

I always thought that painting a flat surface, or observing someone else doing it, is such a pleasurable activity as it ensures a steady supply of dopamine due to the progress towards completion beings so apparent. Your opinion? #

Your observation about the pleasure derived from painting or observing painting on a flat surface taps into a fascinating intersection of psychology, neuroaesthetics, and the philosophy of art. The gradual unfolding of a visual creation does indeed stimulate a range of psychological responses, including the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure, reward, and motivation.

The process of painting or observing painting involves several cognitive and emotional layers. Firstly, there is the element of anticipation and expectation. As a painting progresses, the observer or the artist anticipates the final outcome, creating a sense of expectation. This anticipation stimulates the brain’s reward system, leading to the release of dopamine, which in turn reinforces the behavior, making it pleasurable and motivating the individual to continue engaging in the activity.

Moreover, the act of painting and the observation of this process can be considered a form of problem-solving, where each brushstroke contributes to the resolution of an aesthetic “problem.” The incremental nature of this resolution provides continuous feedback, which is satisfying on a cognitive level. Each step towards completion is visually apparent, offering immediate gratification and a tangible sense of progress. This continuous feedback loop not only encourages the continuation of the activity but also contributes to a state of flow, a concept introduced by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Flow is characterized by complete immersion and enjoyment in the process, leading to heightened creativity and productivity. The conditions for experiencing flow are well met in the context of painting, where skills are applied to challenging tasks with immediate feedback.

The visual and aesthetic elements of painting also play a crucial role in its psychological impact. The appreciation of beauty, whether in the form of color harmonies, composition, or thematic expression, engages the brain’s reward circuits. Neuroaesthetic research suggests that the perception of beauty in art can trigger the release of dopamine in the orbitofrontal cortex, an area of the brain associated with reward and pleasure.

Furthermore, the social and communicative aspects of observing someone else paint—whether in person or through media—add another layer of enjoyment. This observation can create a sense of connection and empathy with the artist, as viewers vicariously experience the creative process, share in the anticipation of the artwork’s completion, and appreciate the skill and intention behind each decision.

In summary, the pleasure derived from painting or observing painting is multifaceted, involving a complex interplay of anticipation, cognitive engagement, aesthetic appreciation, and social connectivity. These elements collectively stimulate the brain’s reward pathways, making the activity intrinsically rewarding and motivating.

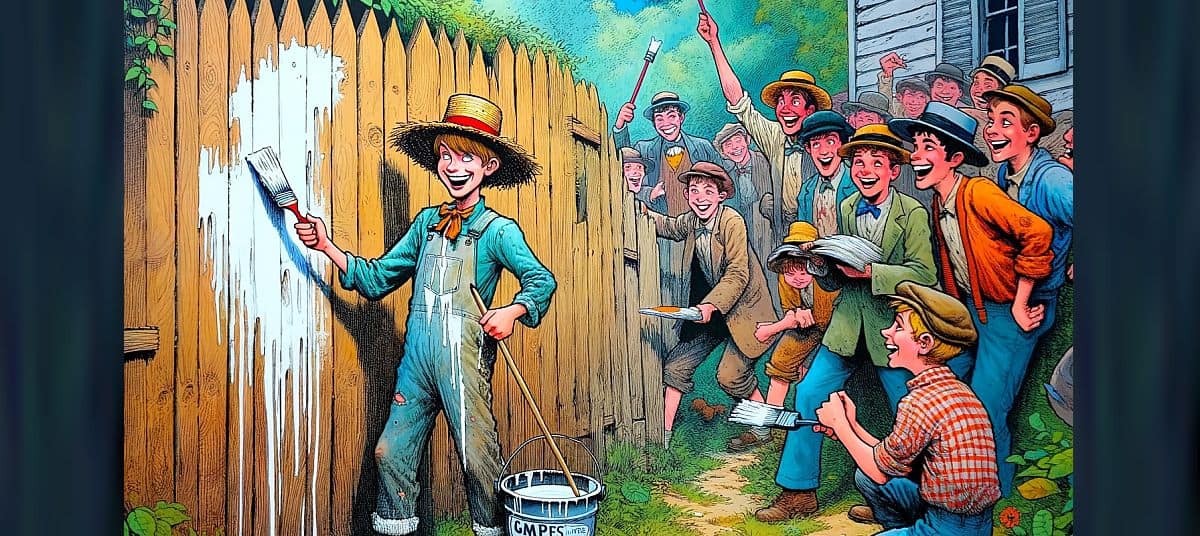

Was this idea exploited by Huckleberry Finn? #

The scene from Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” where Huck Finn exploits the idea of work as pleasure, offers an intriguing case study related to your observation about painting and dopamine release. In Chapter Two, “The Boys Escape Jim”—though the episode you’re likely referring to occurs in Chapter Three, titled “A Good Going-over”—Huck Finn is tasked with whitewashing a fence. Initially, Huck views this task with disdain, seeing it as laborious work. However, the scenario quickly shifts when he cleverly reframes the activity of fence painting as a rare and enjoyable opportunity.

Huck’s transformation of the fence painting into a desirable activity for his friends operates on several psychological levels similar to those involved in the pleasure of painting or observing painting. By pretending to take great pleasure in the task and suggesting that not everyone is capable of performing it to such a high standard, Huck taps into a fundamental human psychology—valuing something more highly when it is perceived as rare or requiring special skills. As his friends watch him work, they become eager to participate, believing the activity to be enjoyable and rewarding.

This situation cleverly exploits several psychological principles:

Social Proof and Conformity: Huck’s apparent enjoyment of the task serves as a social cue to his friends that the activity is desirable, leading them to conform to the perceived group norm of finding pleasure in the work.

Scarcity and Exclusivity: By suggesting that only a select few can do the job “just so,” Huck increases the perceived value of the activity, making it more desirable. The scarcity principle triggers a desire in his friends to be part of the exclusive group that can paint the fence.

The Overjustification Effect: This psychological effect occurs when an external incentive (like the opportunity to paint the fence) decreases a person’s intrinsic motivation to perform a task they initially find uninteresting. However, in Huck’s scenario, the external incentive (being allowed to paint) paradoxically increases the perceived intrinsic value of the task.

While the mechanism here is more socially and psychologically complex than the straightforward pleasure of observing progress in a task like painting, the core idea of manipulating perceptions to increase engagement and satisfaction is similar. Huck Finn’s manipulation of his friends’ desire to participate in painting the fence demonstrates an early understanding of how perceived value and the psychology of work and play can be altered to transform a mundane task into a sought-after activity. This transformation hinges not on the neurobiological stimulation of dopamine release through personal achievement or aesthetic appreciation, but rather through social dynamics and the psychological impact of perceived value and exclusivity.