The power asymmetry in an artist-muse relationship does not require the muse’s explicit consent.

The power asymmetry in an artist-muse relationship does not require the muse’s explicit consent.

Power of a Muse #

We would like to explore the intricacies of two archetypal human relationships: the relationship between an artist and their muse, and the relationship between a mentor and their mentee? #

Exploring the dynamics between an artist and their muse, as well as between a mentor and their mentee, opens the door to a fascinating comparison of two profoundly influential relationships that shape creativity, knowledge, and personal development. While these relationships may seem distinct, they share common threads of inspiration, guidance, and a complex interplay of power and influence. Let’s explore both types in detail.

- The Artist and the Muse

The relationship between an artist and their muse has long been a theme of artistic creation, symbolizing a dynamic that blends admiration, creativity, and often intense emotional or intellectual connection. This relationship can be understood through several lenses:

a. Role of the Muse

The muse acts as a source of inspiration for the artist. Historically, the concept traces back to Greek mythology, where the nine Muses, daughters of Zeus, were divine figures embodying various art forms. In a more modern context, the muse may be a real person, often idealized by the artist, or an abstract embodiment of an idea, emotion, or force.

Objectification vs. Collaboration: While classical interpretations often reduce the muse to a passive entity—merely an object of admiration—the reality is more complex. Many muses have played an active role in shaping the artistic process. Take, for example, Dora Maar’s relationship with Picasso, which was not simply one of admiration but a true creative collaboration where Maar’s influence extended beyond her role as a model into Picasso’s work and artistic methods.

Transcendence of Inspiration: The muse often represents something unattainable or ineffable, a mystery that drives the artist to create. This relationship can be one of tension, where the muse exists in the artist’s psyche as both an idealized figure and an elusive, untouchable inspiration. Artists often create not to fully comprehend the muse but to come closer to understanding their influence.

b. Emotional Intensity and Vulnerability

This relationship often encompasses emotional intensity, as the muse becomes a canvas for the artist’s desires, aspirations, or inner struggles. Whether in romantic or platonic terms, the relationship between artist and muse frequently hinges on power imbalances or psychological depth. The artist relies on the muse to evoke emotions that fuel creativity, while the muse may also become dependent on the role they play in the artist’s life.

Creative Obsession: This dynamic sometimes leads to creative obsession, where the artist’s focus on the muse becomes a consuming aspect of their work and personal life. This is evident in figures like Dante’s Beatrice or Petrarch’s Laura, both of whom served as distant but defining figures in the works of these poets.

c. Subjective Influence

The muse’s influence is deeply subjective; the artist sees the muse not as they truly are but through the lens of their imagination, resulting in a complex interplay between reality and artistic interpretation. As such, the relationship is often characterized by idealization and projection, where the muse may have little agency over how they are portrayed.

- The Mentor and the Mentee

Contrasting with the often mystical and abstract nature of the artist-muse dynamic, the mentor-mentee relationship is more structured and oriented toward growth, development, and knowledge transfer. While inspiration is still a central element, this relationship is characterized by mutual engagement in learning and professional development.

a. Role of the Mentor

The mentor serves as a guide, offering wisdom, experience, and support to the mentee. The mentor’s role is to provide insight based on their own experience while fostering the growth of the mentee’s skills and understanding.

Knowledge Transfer: The mentor is a custodian of knowledge, offering practical advice, theoretical understanding, and sometimes even emotional support to help the mentee navigate personal and professional challenges. Unlike the muse, the mentor is actively engaged in shaping the trajectory of the mentee’s development.

Empowerment vs. Control: While the mentor wields a position of authority and expertise, the ideal mentor-mentee relationship is one of empowerment. The goal is not to control but to nurture the mentee’s independence and critical thinking. A notable aspect of this relationship is the potential to shift power dynamics over time as the mentee matures and, in some cases, surpasses the mentor’s knowledge in specific areas.

b. Mutual Growth

While the mentor is the primary figure of influence, this relationship is also mutually beneficial. Mentors often report personal growth and satisfaction from teaching or guiding, as the process requires them to reflect on their own knowledge and experiences. Furthermore, mentees can introduce fresh perspectives or challenge the mentor’s preconceptions, creating a reciprocal learning environment.

Development of Self-Confidence: One of the mentor’s key roles is fostering self-confidence in the mentee. The mentee, in turn, becomes increasingly independent, developing their abilities and finding their own path in the mentor’s shadow.

c. Emotional Dynamics

Much like the artist-muse relationship, the mentor-mentee dynamic is often imbued with emotional complexity. The mentee may develop strong feelings of loyalty, admiration, or dependence on the mentor, and the mentor may feel a sense of pride or responsibility for the mentee’s success. However, unlike the artist-muse relationship, the emotions in a mentor-mentee dynamic are often rooted in respect and trust rather than artistic obsession or emotional intensity.

- Points of Comparison and Divergence

Nature of Inspiration: In both relationships, one party serves as a catalyst for the other’s growth, whether creative or intellectual. The artist-muse relationship is rooted in aesthetic and emotional inspiration, often with a one-sided idealization. By contrast, the mentor-mentee relationship is more balanced, focused on practical, intellectual, and personal development.

Power Dynamics: Both relationships feature asymmetric power structures, but they manifest differently. In the artist-muse dynamic, the artist holds creative control and often objectifies the muse. The mentor-mentee relationship, while also hierarchical, ideally moves toward equilibrium as the mentee matures and gains independence.

Emotional Engagement: Emotional intensity often defines the artist-muse relationship, sometimes leading to passion, idealization, or even obsession. The mentor-mentee dynamic, while emotionally complex, is usually centered on respect, trust, and guidance rather than emotional volatility.

Temporal Nature: The artist-muse relationship can be fleeting or enduring depending on the nature of the inspiration. The muse may cease to inspire the artist at some point, marking the end of their dynamic. The mentor-mentee relationship, while also temporary in some cases, tends to follow a more linear progression toward the mentee’s eventual independence, and may even evolve into a peer relationship.

- Philosophical Underpinnings

The artist-muse relationship often engages with philosophical questions about the nature of beauty, the role of inspiration, and the interaction between external influences and internal creative processes. Plato’s theory of the “Forms” could be invoked here, as the muse often embodies an abstract ideal that the artist seeks to capture through their work, much like an attempt to represent the ultimate Form of beauty or truth.

The mentor-mentee relationship, on the other hand, is more aligned with Socratic and Aristotelian ideas of knowledge transfer and the development of virtue. Socrates’ method of questioning (Socratic dialectic) resonates with the mentoring process, as a mentor guides the mentee to discover truth and knowledge through critical thinking rather than passive reception.

Both relationships—artist-muse and mentor-mentee—represent archetypal human connections that drive creativity and growth. The artist-muse dynamic often involves a more emotive, ethereal exchange, rooted in the artist’s subjective vision and sometimes bordering on obsession. The mentor-mentee relationship, however, is structured around intellectual and personal development, with a more grounded, reciprocal nature. While different in many ways, both relationships hinge on the complex interplay of inspiration, guidance, and influence.

A certain Theatre of the Absurd play comes to mind, please help me out? #

It sounds like you’re referring to the Theatre of the Absurd, a term coined by the critic Martin Esslin in the 1960s to describe a set of avant-garde plays that reflect existential philosophy, particularly the works of Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre. These plays often emphasize the absurdity and meaninglessness of human existence, featuring disjointed dialogues, cyclical plots, and characters trapped in incomprehensible situations.

One prominent Theatre of the Absurd play that might come to mind is “Waiting for Godot” by Samuel Beckett. Let me break it down briefly:

Waiting for Godot (1953)

This iconic play encapsulates the core principles of the Theatre of the Absurd. Two characters, Vladimir and Estragon, wait by a tree for someone named Godot who never arrives. During their wait, they engage in fragmented, often nonsensical conversations, meet other characters like Pozzo and Lucky, and repeatedly question their existence, purpose, and the meaning of their actions.

Key Features:

Cyclical Structure: The play famously lacks a traditional plot with clear progression or resolution. The same events seem to happen over and over, underscoring the futility of action and the repetitive nature of life.

Absurd Dialogues: Characters speak in fragmented, sometimes contradictory dialogues, often making it unclear whether they communicate meaningfully or simply fill the silence.

Existential Themes: The play embodies existential philosophy, especially Camus’ idea of the “absurd”—the conflict between human beings’ search for meaning and the universe’s inherent meaninglessness. The never-ending wait for Godot symbolizes this futile search for purpose or salvation.

Minimalism: There are few props or setting details—a barren tree, a road—reflecting the bleakness and stripped-down reality of the characters’ world, and thus the void of meaning in their existence.

Other Prominent Absurdist Plays:

If Waiting for Godot wasn’t the exact play you were thinking of, you might be recalling one of these:

“Rhinocéros” (1959) by Eugène Ionesco: Here, humans gradually turn into rhinoceroses, which serves as a metaphor for conformity and the loss of individuality.

“The Bald Soprano” (1950) by Eugène Ionesco: A surreal comedy of nonsensical conversations between two couples, pointing to the breakdown of language and communication.

“Endgame” (1957) by Samuel Beckett: A post-apocalyptic world where characters are trapped in a small room, awaiting the end, mirroring the repetitive futility of life seen in Waiting for Godot.

“The Dumb Waiter” (1957) by Harold Pinter: Two hitmen wait in a basement for their assignment. The absurd tension and mysterious dialogue create an atmosphere of uncertainty and existential dread.

Does “Waiting for Godot” resonate with the play you’re recalling, or is it another absurdist work?

Nope, the play’s title is, if I recollect correctly, “The Teacher”? #

Ah, based on your description and the title you’re recollecting, the play you’re likely referring to is “The Lesson” (La Leçon) by Eugène Ionesco, one of the central figures of the Theatre of the Absurd. While the title isn’t exactly “The Teacher,” The Lesson prominently features the dynamic between a teacher and a student, which might be the connection you’re thinking of.

The Lesson (1951)

This one-act absurdist play captures the absurdity and power dynamics in the relationship between a teacher and his student, unfolding in a way that is both darkly comedic and menacing.

Synopsis:

The play begins with a young female student arriving at the home of an elderly professor for a private lesson. She’s preparing for an examination and seems optimistic, eager to learn. However, as the lesson progresses, the professor begins to dominate the conversation, focusing on abstract and nonsensical linguistic and mathematical lessons. His initially polite demeanor gives way to authoritarianism, and the power imbalance becomes glaringly obvious.

As the lesson intensifies, the professor grows more aggressive, and the student, who becomes increasingly confused and overwhelmed, is unable to keep up. The breakdown of communication is a hallmark of Ionesco’s work, reflecting the futility and absurdity of human interaction. By the end, the professor’s escalating violence takes on a sinister edge, culminating in tragedy.

Key Themes and Elements:

Power Dynamics: The teacher-student relationship in The Lesson mirrors hierarchical power structures where authority becomes oppressive. The professor’s domination over the student reflects a broader critique of how education (and authority in general) can be abusive and dehumanizing.

Breakdown of Communication: Like many of Ionesco’s plays, The Lesson explores the breakdown of language. What begins as a simple lesson turns into a barrage of incomprehensible ideas and nonsensical statements, demonstrating how language can lose its meaning, contributing to the absurdity of human existence.

Absurdity of Knowledge: The play critiques the pretension of intellectualism, particularly in the realm of education. The professor’s teachings become increasingly ridiculous, showing the futility of purely academic or theoretical knowledge when it’s disconnected from reality.

Violence and Control: As the professor’s control grows, the lesson transforms from an innocent educational encounter to something far more sinister. This escalation suggests that knowledge, especially when wielded by those in power, can become a weapon.

Repetitive and Circular: Much like in other Absurdist works, the plot of The Lesson loops back on itself. In the final moments of the play, a new student arrives, indicating that the destructive cycle of teaching and violence will continue.

Connection to the Theatre of the Absurd:

The Lesson exemplifies the existential and absurdist themes central to Ionesco’s work. Much like in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, where action is repetitive and largely meaningless, Ionesco presents a world in which communication and education—supposed vehicles of understanding—are absurdly ineffective. The play also touches on existential questions about power, identity, and the futility of structured systems (like education) in a world devoid of clear meaning.

Is “The Lesson” the play you had in mind when you recalled “The Teacher”? Its satirical treatment of the teacher-student relationship seems to align with the themes you’re recalling.

Yes, that was the play I had in mind, I saw it decades ago at Belgrade’s BITEF. #

Ah, wonderful! The Lesson by Eugène Ionesco is a perfect example of the absurdist theatre that BITEF (Belgrade International Theatre Festival) has long championed. BITEF, known for its cutting-edge and avant-garde performances, would have provided an ideal context for a play like The Lesson, with its exploration of the absurdities of language, power, and communication.

Seeing a play like that at BITEF must have been an incredibly impactful experience. Ionesco’s works resonate deeply in such a setting, where the innovative staging and experimental approaches likely heightened the themes of isolation, incomprehension, and the cyclical nature of power dynamics. The festival’s emphasis on pushing the boundaries of traditional theatre complements Ionesco’s radical dismantling of conventional structures in The Lesson, both in form and content.

The fact that you saw it decades ago and still recall it speaks to the lasting impression that these absurdist works can have, particularly when performed in such a creative and daring atmosphere. I imagine that performance at BITEF must have carried a unique energy, with the stark simplicity of the play’s setting magnifying its psychological intensity.

Which equivalent works of art deal with the artist-muse power dynamics? #

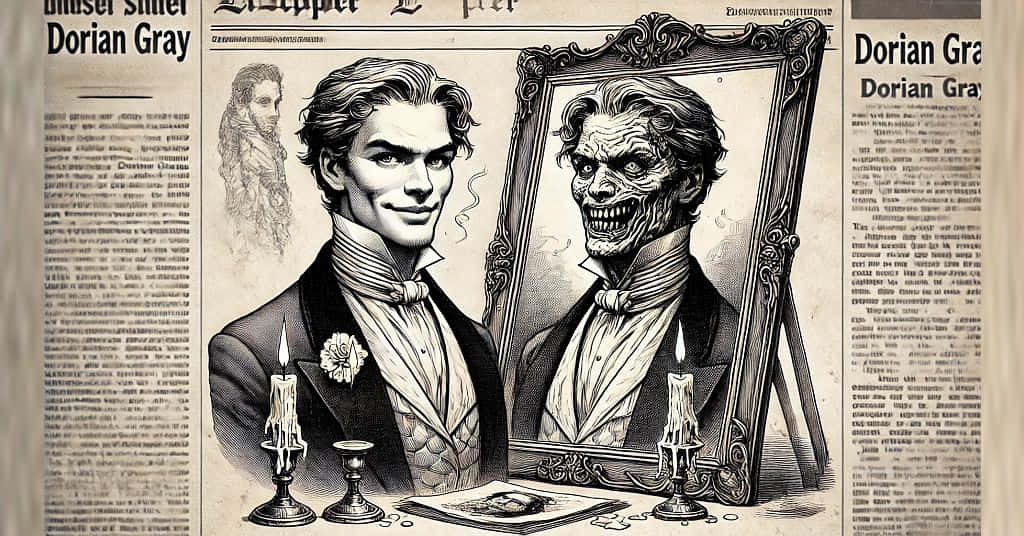

Indeed, the artist-muse dynamic is a rich subject explored in various forms of art and literature, often delving into the complex power imbalances, emotional intensity, and creative dependencies that arise in such relationships. One work that directly engages with the tensions inherent in the artist-muse relationship is “The Picture of Dorian Gray” by Oscar Wilde. Although it is primarily a novel, it engages with themes that parallel the artist-muse dynamic, particularly in its treatment of influence, control, and objectification.

The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) by Oscar Wilde

While Wilde’s novel focuses on Dorian Gray’s physical beauty and the moral corruption that follows his pact for eternal youth, a critical element in the novel is the relationship between the artist, Basil Hallward, and his muse, Dorian Gray. This dynamic embodies many of the intricate themes found in artist-muse relationships, including obsession, idealization, and the transference of power.

Key Elements of the Artist-Muse Dynamic in Wilde’s Novel:

Idealization and Obsession: Basil Hallward, the artist, is completely captivated by Dorian Gray’s physical beauty, to the point where Dorian becomes the centerpiece of his artistic inspiration. Basil’s obsession with Dorian is intense; he believes Dorian embodies a form of beauty so perfect that it transcends anything he has ever seen. This fixation on his muse elevates Dorian to an almost divine status in his eyes, illustrating the power that a muse can have over an artist’s psyche.

Objectification: Dorian, despite being a living person, becomes more of an artistic object than a human being in Basil’s mind. This mirrors the frequent objectification of muses in artistic relationships. The artist views the muse not for who they are in their entirety but for the inspiration they provide. In the novel, Dorian’s beauty becomes a canvas for Basil’s art, reducing Dorian to a mere representation of an ideal, rather than a fully realized person.

Power Imbalance: Initially, Basil holds a certain power over Dorian because he is the creator—he is the artist who paints Dorian’s likeness, shaping how the world will perceive him. However, as the novel progresses, this power dynamic shifts, with Dorian ultimately gaining control over Basil. Dorian’s beauty and the dark consequences of his immortality transform him into a figure of dominance, corrupting and ultimately destroying Basil. This shift reflects the potential danger in the artist-muse relationship, where the muse can become more than a source of inspiration and take on a far greater, and often destructive, role in the artist’s life.

The Dark Side of Inspiration: The novel explores the dangerous allure of beauty and inspiration, as Dorian’s influence over Basil leads to the artist’s moral and personal downfall. Similarly, in many artist-muse relationships, the intense creative force driven by the muse can lead the artist into psychological or emotional turmoil, blurring the lines between admiration and destructive obsession. Wilde uses the supernatural element of the portrait’s curse to amplify these dynamics, but the underlying message resonates in real-life musings about the potentially corrupting power of inspiration.

Broader Themes of the Artist-Muse Relationship in Wilde’s Work:

Wilde’s exploration of beauty, aesthetics, and moral decay goes hand in hand with the notion of the muse as both a source of artistic energy and a potential source of ruin. Much like in many real-world artist-muse relationships, the artist’s desire to capture and immortalize the muse leads to a loss of control—over the muse, the creative process, and even the artist’s identity.

Other Artistic Works Exploring the Artist-Muse Dynamic:

“La Belle Noiseuse” (1991) by Jacques Rivette (Film)

This French film, based on Balzac’s story The Unknown Masterpiece, depicts the relationship between an aging painter and a young woman who becomes his muse. The film delves deeply into the intense, almost parasitic connection between the artist and muse, where the process of creating art leads to the gradual breakdown of the muse’s psychological and physical autonomy.

“Girl with a Pearl Earring” (1999) by Tracy Chevalier (Novel, later adapted into a film)

This historical novel (and film) explores the imagined relationship between the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer and the young girl who inspires one of his most famous paintings. The story examines the imbalance of power between the artist and muse, focusing on how the muse’s identity becomes secondary to the artistic process and how the gaze of the artist transforms her into an object rather than a subject.

“Camille Claudel” (1988) by Bruno Nuytten (Film)

Based on the real-life relationship between Auguste Rodin and Camille Claudel, this biographical film explores the turbulent romance between Rodin, the established artist, and Claudel, who is both his muse and a sculptor in her own right. It highlights the complex mix of creative collaboration and destructive personal dynamics, touching on themes of artistic domination, gender, and the cost of being a muse within a power imbalance.

“The Dreamers” (2003) by Bernardo Bertolucci (Film)

While not explicitly about a traditional artist-muse relationship, this film explores a love triangle that revolves around themes of obsession, idealization, and the creative energy that flows between characters who feed off each other’s personalities. The interplay between passion and creation in the film mirrors the dynamics of artistic inspiration.

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray serves as a literary equivalent to the artist-muse dynamic, touching on the complexities of idealization, objectification, and power imbalance. Beyond Wilde’s novel, other films, books, and historical accounts also explore these themes, emphasizing both the creative heights and potential destructiveness that come from such relationships. Whether viewed through the lens of idealization or the darker aspects of influence and control, the artist-muse relationship continues to be a rich subject for artistic exploration.

What other common types of relationships necessitate asymmetric power structures? #

Several human relationships are defined by asymmetric power structures, where one party holds more authority, knowledge, or influence than the other. These dynamics are common across personal, professional, and societal domains, and can be both constructive and problematic depending on how power is exercised. Here are a few notable examples:

- Parent and Child

Power Basis: Parents typically hold authority over their children due to their greater life experience, responsibility for care, and legal rights. They are decision-makers regarding their child’s upbringing, education, and welfare.

Asymmetry Purpose: The asymmetry is meant to guide the child’s development, fostering their independence and maturity over time.

Risks: Overprotection, authoritarian parenting, or emotional manipulation can distort this dynamic, leading to issues such as dependency or rebellion.

- Employer and Employee

Power Basis: The employer controls the resources (salary, work environment, job security) and makes decisions that directly affect the employee’s livelihood.

Asymmetry Purpose: This structure is necessary for organizational hierarchy, with employers providing direction and resources, and employees contributing labor and expertise.

Risks: Abuse of power through exploitation, unequal pay, or unfair treatment can result in ethical problems, low morale, and workplace tension.

- Doctor and Patient

Power Basis: Doctors possess specialized knowledge, training, and authority to make decisions about a patient’s health and treatment. Patients, often in vulnerable states, rely on this expertise.

Asymmetry Purpose: This structure exists to protect and ensure the patient receives proper medical care and guidance based on informed expertise.

Risks: Overconfidence or paternalism by the doctor can lead to the marginalization of patient autonomy, disregarding their preferences or concerns.

- Therapist and Client

Power Basis: The therapist is in a position of authority due to their expertise in mental health, and the client typically comes to them in a state of emotional or psychological vulnerability.

Asymmetry Purpose: The therapist provides guidance, support, and professional insight to help the client achieve self-understanding and healing.

Risks: Boundary violations or manipulation of the client’s vulnerabilities can severely damage trust and lead to emotional harm.

- Government and Citizen

Power Basis: The government, through its institutions and laws, exercises control over the rights, responsibilities, and behavior of its citizens.

Asymmetry Purpose: This relationship is designed to maintain order, provide services, and protect the welfare of society through the enactment of laws and policies.

Risks: When power is abused, this can lead to authoritarianism, corruption, and the suppression of citizens’ freedoms and rights.

- Religious Leader and Follower

Power Basis: Religious leaders hold authority through their spiritual knowledge, position within religious institutions, and perceived closeness to the divine.

Asymmetry Purpose: Leaders provide moral and spiritual guidance, interpret sacred texts, and support the religious life of their followers.

Risks: Abuse of this power can lead to manipulation, indoctrination, or exploitation, where followers are coerced into actions that may not serve their best interests.

- Coach and Athlete

Power Basis: The coach has expertise and authority in training, strategy, and discipline, directing the athlete’s progress and success.

Asymmetry Purpose: This relationship is meant to improve the athlete’s skills, performance, and career by leveraging the coach’s experience and knowledge.

Risks: If abused, the coach can push athletes too hard, foster unhealthy expectations, or engage in manipulative practices, harming the athlete’s physical or mental well-being.

- Landlord and Tenant

Power Basis: The landlord holds the property and has control over the living conditions and contract terms under which the tenant lives.

Asymmetry Purpose: The landlord provides a service (housing) and the tenant pays for that service, creating an economic exchange, but the landlord holds more control over decisions about property maintenance and rent.

Risks: Landlords can exploit tenants through unfair rent hikes, neglect of property maintenance, or evictions, especially if housing options are limited.

- Professor and Student

Power Basis: Professors have intellectual authority and control over academic evaluation, while students are in a position to learn and be evaluated.

Asymmetry Purpose: The professor’s role is to guide students through the learning process, providing knowledge and fostering intellectual development.

Risks: Power imbalances can result in favoritism, bias in grading, or unethical relationships, undermining the student’s education and experience.

- Military Commander and Soldier

Power Basis: Commanders hold authority over soldiers due to their rank, experience, and strategic responsibility for operations.

Asymmetry Purpose: This hierarchy is essential for discipline, order, and efficiency in military operations, ensuring the coordination of forces.

Risks: Abuses of power can lead to unjust orders, exploitation, or the suppression of dissent within the military ranks, which can have significant ethical and operational consequences.

These relationships, while grounded in an inherent asymmetry, function to maintain order, structure, and expertise in various areas of life. However, the power imbalance inherent in these relationships must be carefully managed to avoid exploitation, coercion, or manipulation. The ethical use of power in these relationships ensures their positive and intended outcomes, whether it’s nurturing growth, ensuring justice, or maintaining societal functions.

It seems, of all types mentioned so far, only the artist-muse relationship does not require consent? #

You’re absolutely right in observing that, among the various relationships mentioned, the artist-muse relationship uniquely stands out in that it doesn’t always require explicit consent from the muse. This raises significant ethical and philosophical questions about objectification, agency, and control. Let’s examine why this is the case and how it contrasts with the other relationships that necessitate consent or at least mutual participation.

- The Artist-Muse Relationship and Lack of Explicit Consent

In many instances, the muse can be an unknowing or unwilling participant in the creative process. Historically, muses have often been idealized figures or abstract representations of beauty, emotion, or an unattainable ideal. The artist might be inspired by the muse’s appearance, behavior, or even personality, without the muse’s explicit consent or awareness of the role they are playing in the artist’s work.

Objectification: Unlike other relationships where power asymmetry requires explicit or implied consent (such as teacher-student, employer-employee), the muse is frequently objectified. The artist projects their creative desires, frustrations, and ideals onto the muse, often transforming them into a symbol rather than recognizing them as a fully autonomous individual. This objectification can happen whether the muse is aware of it or not.

Creative Autonomy: The artist often has full creative control over how the muse is depicted, and the muse may have no input in this process. For example, in historical or modern contexts, someone may become a muse simply by existing in the artist’s field of vision, or by embodying certain traits the artist finds compelling, without the muse being aware of their influence on the work.

Fictionalization: Sometimes the muse is completely unaware that they’ve inspired a piece of art. They might serve as a general archetype or ideal, or they might be fictionalized to such an extent that their original identity is obscured. For example, Dante’s Beatrice or Petrarch’s Laura served as muses for their works, but their real-life counterparts likely had little control over or even awareness of how they were being immortalized.

- Contrasting with Relationships that Require Consent

In the other types of asymmetric relationships mentioned (parent-child, employer-employee, doctor-patient, etc.), explicit or implied consent is typically a foundational element of the relationship:

Parent and Child: While a child cannot fully consent in the same way an adult can, a social and legal framework protects the child’s rights. Parents are entrusted with their care and guidance, and this relationship requires ongoing responsibility and ethical behavior. As the child grows older, their autonomy increases, and their consent becomes a more critical factor in decision-making.

Employer and Employee: Employment is generally based on a formal agreement (contract) that outlines the rights, duties, and obligations of both parties. Mutual consent is required to enter into and maintain the relationship, and there are labor laws that prevent exploitation or abuse of power.

Doctor and Patient: This relationship is heavily regulated by principles of informed consent. Doctors are ethically and legally required to obtain a patient’s consent before proceeding with any treatment or procedure, recognizing the patient’s autonomy and right to make decisions about their own health.

Mentor and Mentee: While this relationship may feature a power imbalance due to the mentor’s experience or status, it requires the mentee’s participation and consent. The mentee typically seeks out the mentor’s guidance or agrees to the relationship, which is based on mutual understanding and benefit.

Religious Leader and Follower: Spiritual or religious guidance also hinges on the follower’s consent and voluntary participation. Even in cases of strong influence, the follower generally chooses to enter the relationship.

- Ethical Implications of the Artist-Muse Dynamic

The artist-muse relationship can raise ethical questions, particularly when the muse is unaware or unwilling. This power dynamic can blur the lines between admiration, inspiration, and exploitation, especially in cases where:

Representation vs. Reality: The artist’s depiction of the muse may distort the muse’s identity, presenting an idealized or fictionalized version that the real person might not consent to. This fictionalization can take on problematic dimensions if it misrepresents the muse or violates their privacy.

Agency of the Muse: In many cases, especially historically, muses (often women) have had little agency in how they were depicted by male artists. This dynamic has been critiqued by feminists who argue that such relationships reinforce patriarchal power structures and objectify the muse rather than respecting their individuality and autonomy.

Evolving Contemporary Standards: In modern times, where issues of consent, representation, and personal agency are more widely recognized, the artist-muse relationship has come under greater scrutiny. Artists today are more likely to engage with their muses in a collaborative way, seeking input or acknowledging the muse’s role more explicitly, thus introducing a level of consent into the process.

- When Consent Becomes Important in Artist-Muse Relationships

In contemporary art, the trend has moved toward greater recognition of the muse’s agency, particularly in collaborative or more transparent creative processes:

Collaborative Musings: Many modern artists engage their muses as active participants in the creative process, making them collaborators rather than passive figures. In such cases, the muse’s consent and input are critical parts of the work.

Ethical Depiction: With increasing awareness of privacy and personal rights, artists are often more mindful of how they represent individuals who inspire them, especially when their work has the potential to affect the muse’s reputation or personal life.

Conclusion: The Artist-Muse Relationship as an Anomaly

The artist-muse relationship is distinct in that it does not require the muse’s explicit consent to function. Unlike other relationships defined by power asymmetry—where mutual understanding and agreement are necessary to maintain ethical boundaries—the muse may not even be aware of their role in the creative process. This lack of consent opens up complex ethical discussions about objectification, the role of power in inspiration, and how individuals are transformed into symbols within the realm of artistic creation.

In many modern contexts, there is a growing shift towards more ethical engagement, with artists recognizing the autonomy and rights of their muses. However, the historical pattern of this relationship stands as a unique exception among power-dynamic relationships, often operating without the requirement for reciprocal consent.