A blend of hurt, frustration, cognitive rumination, and behavioral withdrawal.

A blend of hurt, frustration, cognitive rumination, and behavioral withdrawal.

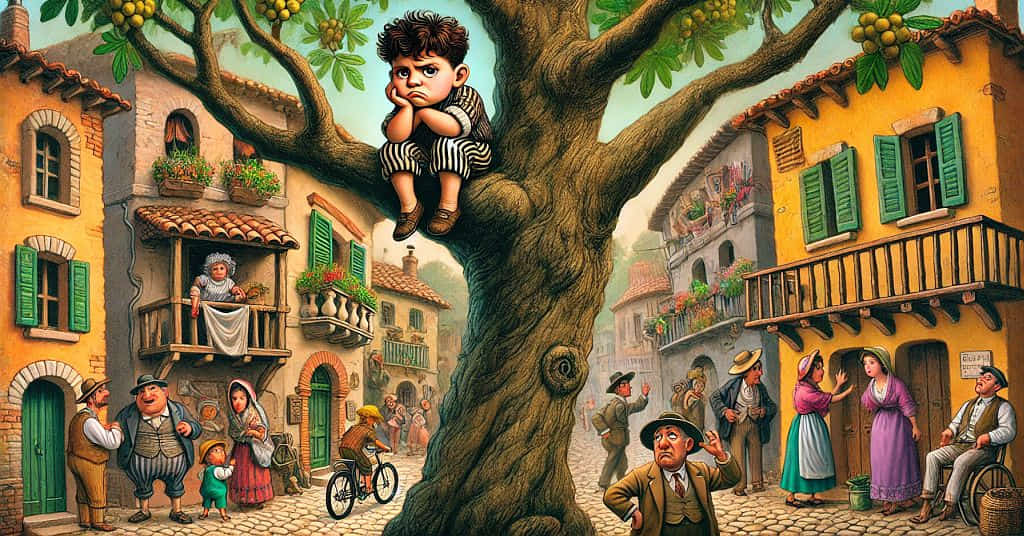

Sulking #

Is it true that kids who sulk develop a cunning cutoff game in their adult relationships? #

The notion that children who sulk develop a “cunning cutoff game” in their adult relationships is an interesting psychological hypothesis, but it is not universally established as a fact. The behavior of sulking in childhood can be a response to a perceived lack of control or an inability to express emotions effectively. Over time, if these coping mechanisms are reinforced or left unaddressed, they might evolve into more sophisticated forms of emotional regulation or manipulation in adulthood.

Here’s how this might work:

Sulking as a Defense Mechanism: Sulking in childhood is often a passive-aggressive way of expressing dissatisfaction, frustration, or hurt without directly confronting the issue. It’s a form of silent protest, where the child may be seeking attention, validation, or control over a situation.

Internalization of Behavior: If a child finds that sulking is an effective way to gain control or get what they want, this behavior can become internalized. As they grow older, they may refine this behavior, learning to withdraw emotionally or cut off communication as a means of exerting power in relationships.

Development of ‘Cutoff’ Strategies: In adulthood, the pattern of withdrawing or cutting off communication can manifest as a sophisticated coping mechanism. This might involve emotionally distancing oneself from others, using silence as a form of punishment, or disengaging entirely when conflicts arise. Such strategies can be seen as a form of emotional control or protection, developed from the early behaviors of sulking.

Cunning in Relationships: The term “cunning” implies a calculated or strategic use of these behaviors. Indeed, adults who have honed these skills might use emotional cutoff as a deliberate strategy to manage relationships, maintain control, or protect themselves from perceived threats. This could be a way of avoiding vulnerability, steering the relationship dynamics, or even manipulating others.

However, it’s essential to recognize that this is not a deterministic outcome. Not all children who sulk will develop such behaviors in adulthood. The development of these traits depends on various factors, including parenting styles, emotional intelligence, social learning, and personal growth. Additionally, individuals can change their behavioral patterns through self-awareness, therapy, and healthier communication practices.

In summary, while there is a plausible psychological trajectory from childhood sulking to adult emotional cutoff behaviors, this is not a guaranteed or universal outcome. The complexity of human behavior and the influence of various developmental factors mean that such traits are not inevitable but are rather one potential pathway among many.

Let us try and dissect how sulking is experienced subjectively? #

Sulking is a multifaceted emotional experience that can vary significantly depending on the individual and the context. To understand it subjectively, it’s important to consider the various psychological, emotional, and cognitive components that come into play during the act of sulking.

- Emotional State

Hurt and Frustration: At its core, sulking often stems from feelings of hurt or frustration. The individual feels wronged, misunderstood, or unappreciated and experiences a sense of injustice or disappointment.

Anger and Resentment: Sulking can also involve a low-grade, simmering anger or resentment. This anger is often directed at a person or situation that the individual feels powerless to confront directly.

Sadness and Vulnerability: Beneath the surface, there may be a sense of sadness or vulnerability. Sulking can be a way of coping with feelings of inadequacy, rejection, or emotional pain, often without fully acknowledging these feelings to oneself.

- Cognitive Processes

Ruminative Thoughts: During sulking, the individual often engages in ruminative thinking, replaying the perceived slight or injustice in their mind. This can reinforce the feelings of hurt and frustration, creating a feedback loop that deepens the emotional state.

Perception of Injustice: Sulkers may dwell on the perceived unfairness of the situation, leading to a heightened sense of grievance. This cognitive fixation can make it difficult to move past the incident or see alternative perspectives.

Silent Narrative: Sulking often involves an internal narrative where the individual justifies their behavior and solidifies their position as the wronged party. This can make it challenging to communicate openly or resolve the issue constructively.

- Behavioral Aspects

Withdrawal and Non-Communication: Sulking is characterized by withdrawal from active engagement. The individual may avoid eye contact, refuse to speak, or offer only minimal responses, creating a barrier to resolution.

Passive Resistance: Instead of confronting the issue directly, the individual engages in passive resistance. This can include refusing to participate in normal activities, not fulfilling responsibilities, or subtly undermining the other party’s efforts to mend the situation.

Subtle Signaling: Despite the withdrawal, sulking often involves subtle cues intended to signal distress or dissatisfaction. These might include sighs, body language, or brief, pointed comments. The goal is often to elicit a response or acknowledgment from the other party without overtly expressing the underlying emotions.

- Interpersonal Dynamics

Power and Control: Sulking can be a way of exerting power or control in a relationship. By withdrawing emotionally, the sulker can shift the focus onto themselves, forcing the other party to address their needs or concerns.

Testing Boundaries: The sulking individual may be testing the boundaries of the relationship, seeking to gauge the other person’s willingness to reach out or make amends. This can be a way of assessing how much the other person cares or is willing to invest in the relationship.

Emotional Detachment: In some cases, sulking serves as a protective mechanism, allowing the individual to emotionally detach from a situation that feels overwhelming or hurtful. This detachment can be both a form of self-protection and a way of punishing the other party.

- Internal Conflict

Desire for Resolution vs. Need for Validation: A common internal conflict during sulking is the tension between the desire for resolution and the need for validation. The sulker may want the situation to be resolved but also wants their feelings and perspective to be acknowledged and validated first.

Fear of Rejection: There may also be an underlying fear of rejection or further hurt, which can make the sulker reluctant to re-engage or express their true feelings. This fear can prolong the sulking and make it difficult to move toward resolution.

- Coping Mechanism

Avoidance of Conflict: Sulking can be a way of avoiding direct conflict, especially if the individual finds confrontation anxiety-provoking or believes that their concerns will not be taken seriously. It allows them to express dissatisfaction without engaging in a potentially painful or uncomfortable conversation.

Self-Soothing: For some, sulking serves as a form of self-soothing. By withdrawing and focusing inward, the individual may feel a temporary sense of control or comfort, even if it doesn’t lead to a productive outcome.

- Potential for Growth

- Opportunity for Reflection: Although often seen as a negative behavior, sulking can also be an opportunity for reflection. The period of withdrawal can allow the individual to process their emotions, gain insight into their needs and desires, and consider how to address the situation more constructively in the future.

In sum, sulking is a complex emotional experience that involves a blend of hurt, frustration, cognitive rumination, and behavioral withdrawal. It often serves as a coping mechanism for dealing with perceived injustices or emotional pain, but it can also create barriers to communication and resolution. Understanding the subjective experience of sulking can provide insights into the underlying emotions and motivations that drive this behavior, offering pathways to more effective emotional regulation and interpersonal communication.

Where does stubbornness come from? #

Stubbornness is a multifaceted trait that can emerge from various psychological, developmental, and environmental factors. Understanding where stubbornness comes from involves exploring the interplay between personality, experiences, and learned behaviors.

- Personality and Temperament

Innate Disposition: Stubbornness can be rooted in a person’s innate temperament. Some individuals are naturally more strong-willed or determined, characteristics that can manifest as stubbornness. This trait may be evident even from early childhood, where a child might show a strong preference for independence and a desire to assert their will.

Resilience and Persistence: These personality traits can be positive and adaptive, leading to persistence in the face of challenges. However, when taken to an extreme, they can result in an unwillingness to adapt, compromise, or consider alternative perspectives, leading to stubborn behavior.

- Developmental Influences

Early Childhood Experiences: Stubbornness can develop as a response to early childhood experiences, particularly in relation to how a child’s needs and desires are met. If a child finds that being inflexible or persistent in their demands results in getting what they want, this behavior can be reinforced over time.

Parental Influence: Parenting styles play a significant role. Authoritative parenting, which balances firmness with warmth, can help children learn to negotiate and be flexible. In contrast, overly permissive or authoritarian parenting might contribute to the development of stubbornness, either as a learned behavior (if permissive) or as a form of resistance or defiance (if authoritarian).

Identity Formation: As children grow, they begin to form a sense of identity and autonomy. Stubbornness can emerge as part of this process, where a child or adolescent insists on their views or preferences as a way of asserting their independence and establishing a distinct sense of self.

- Psychological Mechanisms

Fear of Change: Stubbornness can be a defense mechanism against change. For some individuals, change can be threatening, and stubbornness acts as a way to maintain the status quo. This resistance to change can be rooted in a fear of the unknown, a lack of confidence in handling new situations, or a deep-seated need for control.

Cognitive Rigidity: Some people are naturally more cognitively rigid, meaning they have difficulty seeing things from different perspectives or adjusting their thinking when confronted with new information. This rigidity can lead to a stubborn adherence to one’s own ideas or beliefs, even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

Emotional Insecurity: Stubbornness can also arise from emotional insecurity. When individuals feel insecure or uncertain about themselves, they may cling stubbornly to their opinions or decisions as a way of compensating for these feelings of vulnerability. By refusing to budge, they can create a sense of control and stability.

- Social and Environmental Factors

Cultural Norms and Values: Cultural background can influence the development of stubbornness. In some cultures, being assertive and standing one’s ground is valued, and individuals may be socialized to exhibit stubbornness as a positive trait associated with strength and conviction.

Social Reinforcement: Stubbornness can be reinforced socially, especially if it is rewarded or seen as a desirable trait in certain contexts. For example, in competitive environments, stubbornness might be associated with leadership or success, leading individuals to adopt and reinforce this behavior.

Past Experiences: Life experiences, such as dealing with failure, betrayal, or repeated challenges, can make individuals more stubborn. If they’ve learned that compromising or being flexible led to negative outcomes in the past, they may become more resistant to change or compromise in the future as a protective measure.

- Defensive Mechanism

Avoidance of Vulnerability: Stubbornness can serve as a defense against vulnerability. By being inflexible, individuals may avoid situations that require them to be open, adaptable, or emotionally vulnerable. This can be a way to protect oneself from potential disappointment, hurt, or the fear of being wrong.

Ego Protection: A related concept is the protection of one’s ego or self-image. Stubbornness can be a way to defend one’s sense of competence or intelligence. Admitting that one is wrong or needs to change can be threatening to self-esteem, so stubbornness acts as a barrier to protect the ego.

- Cognitive Dissonance

- Avoiding Cognitive Dissonance: Stubbornness can also arise from the discomfort of cognitive dissonance, which occurs when a person holds two conflicting beliefs or when their actions contradict their beliefs. To reduce this discomfort, individuals may become stubborn, refusing to change their beliefs or acknowledge new information that challenges their established views.

- Potential for Growth and Adaptation

- Channeling Stubbornness Positively: While stubbornness is often viewed negatively, it can also be channeled positively as perseverance or tenacity. Recognizing the roots of one’s stubbornness can lead to greater self-awareness and the ability to harness this trait in constructive ways, such as by developing resilience and determination while learning to be more flexible and open to other perspectives.

In conclusion, stubbornness is a complex trait that originates from a combination of innate temperament, early experiences, psychological mechanisms, social influences, and defense strategies. While it can be a challenging behavior to deal with, understanding its roots can help in addressing and potentially transforming it into a more adaptive and balanced approach to life’s challenges.

I meant, stubbornness involved in a sulk? #

Stubbornness in the context of sulking is a specific manifestation of a broader psychological pattern, where an individual becomes entrenched in their emotional state and refuses to engage in dialogue or resolution. To dissect this, let’s explore how stubbornness interacts with sulking on a subjective level.

- Emotional Entrenchment

Refusal to Relinquish Emotional Control: When a person sulks, they are often deeply entrenched in their emotional state—hurt, frustration, or anger. Stubbornness here manifests as a refusal to let go of these emotions or to allow them to be challenged or questioned. The individual may feel that if they give in or engage, they are conceding defeat or invalidating their feelings.

Emotional Righteousness: There’s often a sense of righteousness that accompanies sulking. The sulker might believe they are justified in their feelings, and this conviction fuels their stubbornness. They might think, “I have every right to feel this way,” and thus see any attempt to resolve the issue as an undermining of their justified emotions.

- Cognitive Rigidity

Fixed Mindset: The stubbornness in a sulk is often tied to a fixed mindset. The sulker may rigidly hold onto their perception of the situation, refusing to entertain alternative viewpoints or solutions. This cognitive rigidity reinforces the sulking, as the individual may feel that any compromise would require them to shift their thinking, which they are unwilling to do.

Selective Attention: In a sulk, stubbornness can also involve selective attention to details that support their grievance. The individual might focus exclusively on aspects of the situation that justify their sulking, ignoring or dismissing any information or perspectives that could lead to resolution.

- Power Dynamics

Perceived Power in Withdrawal: Sulking often involves a power dynamic where the individual feels that by withdrawing, they are asserting control over the situation. Stubbornness in this context can be a way of maintaining that power, refusing to re-engage until their emotional needs are met or until the other party acknowledges their hurt or frustration.

Resistance to Concession: The sulker may view re-engagement or reconciliation as a concession, something that would weaken their position or power in the relationship. This resistance to concession is where stubbornness plays a crucial role, as the individual may stubbornly cling to their withdrawal as a means of maintaining the upper hand.

- Fear of Vulnerability

Protection Against Emotional Exposure: Stubbornness in a sulk can be a defense mechanism against vulnerability. Engaging in dialogue or seeking resolution might require the individual to expose their true feelings, admit hurt, or confront aspects of themselves that they find uncomfortable. Stubbornly maintaining the sulk allows them to avoid this vulnerability.

Avoidance of Emotional Risk: There is often a fear that re-engaging too soon might lead to further emotional pain, rejection, or invalidation. The sulker’s stubbornness thus becomes a way of protecting themselves from these perceived risks by staying withdrawn and unresponsive.

- Self-Validation

Reinforcement of Self-Perception: Stubbornness in a sulk can also serve as a way of reinforcing the individual’s self-perception. By refusing to budge, they validate their feelings and justify their emotional response. This stubbornness can be a way of telling themselves, “I am right to feel this way,” which provides a sense of validation and self-affirmation.

Resistance to External Validation: Conversely, the sulker might resist external attempts at validation, seeing them as insufficient or insincere. This resistance further entrenches their stubbornness, as they refuse to be placated or mollified by what they perceive as inadequate gestures from others.

- Stalemate in Communication

Breakdown in Dialogue: Stubbornness in a sulk often leads to a communication stalemate. The individual may refuse to engage in constructive dialogue, insisting on their silence or withdrawal until their conditions or expectations are met. This creates a deadlock where neither party can move forward, as the sulker’s stubbornness blocks any attempts at resolution.

Expectation of Concession: The sulker might stubbornly hold out, expecting the other party to make the first move, apologize, or concede to their perspective. This expectation creates a barrier to communication, as the sulker waits for the other to meet their unspoken demands, often without clearly articulating what those demands are.

- Emotional Inflexibility

Inability to Process Emotions Differently: Stubbornness in sulking is also a form of emotional inflexibility. The individual may struggle to process their emotions in a different way, such as by talking through them or seeking a compromise. Instead, they stubbornly cling to their sulking as the only way to cope with their feelings.

Resistance to Emotional Resolution: The sulker may also resist attempts to resolve the emotional situation because doing so would require them to shift their emotional state, which they might find difficult or undesirable. This resistance can be driven by a stubborn attachment to their current emotional experience, even if it is uncomfortable.

- Potential for Escalation

- Entrenchment Leading to Escalation: Finally, stubbornness in a sulk can lead to an escalation of the conflict. As the sulker remains unyielding, the situation can intensify, leading to greater emotional distance and potentially more significant relational damage. The stubbornness that fuels the sulk can thus turn a temporary emotional response into a prolonged and more serious conflict.

In summary, stubbornness within the context of sulking involves a complex interplay of emotional entrenchment, cognitive rigidity, power dynamics, fear of vulnerability, and a need for self-validation. It serves as both a protective mechanism and a means of maintaining control, but it can also hinder resolution and prolong emotional distress. Understanding these dynamics can help in addressing stubbornness during sulking, fostering more open communication and emotional flexibility.

How much of cognitive rigidity is due to nurture and how much due to nature? #

The development of cognitive rigidity, like many psychological traits, is influenced by both nature (genetics and biology) and nurture (environmental factors, including upbringing and experiences). The interplay between these influences is complex, and while it’s challenging to assign precise percentages, we can explore the general contributions of both nature and nurture to cognitive rigidity.

- Nature (Genetic and Biological Factors)

Genetic Predisposition: Some aspects of cognitive rigidity are believed to be heritable. Studies on personality traits have shown that certain temperamental factors, such as a tendency toward anxiety, perfectionism, or a preference for structure and routine, can be influenced by genetic factors. These traits can contribute to a person’s likelihood of developing cognitive rigidity.

Neurological Factors: Cognitive rigidity is also associated with specific neurological conditions or brain structures. For example, research has shown that individuals with lower levels of cognitive flexibility may have differences in the functioning of the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in planning, decision-making, and adapting to new information. Neurological conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are also linked to cognitive rigidity, suggesting a strong biological component.

Cognitive Style: Some people are naturally more analytical, detail-oriented, and less comfortable with ambiguity, which can contribute to cognitive rigidity. These cognitive styles can have a biological basis, being influenced by how an individual’s brain processes information.

- Nurture (Environmental Factors)

Early Childhood Experiences: Environmental factors during childhood play a significant role in shaping cognitive flexibility or rigidity. Children raised in environments where conformity, strict rules, or rigid thinking are emphasized may develop cognitive rigidity as an adaptive response. Conversely, environments that encourage exploration, critical thinking, and open-mindedness can promote cognitive flexibility.

Parenting Styles: Authoritarian parenting, characterized by strict rules and expectations with little room for questioning or exploration, can foster cognitive rigidity. Children in such environments may learn to think in rigid ways, adhering to black-and-white thinking patterns as they conform to the demands placed on them. In contrast, authoritative parenting, which balances structure with openness and dialogue, tends to encourage more flexible thinking.

Educational and Social Influences: Educational systems that prioritize rote memorization, standardized testing, and rigid curricula can reinforce cognitive rigidity by discouraging creative thinking and problem-solving. Additionally, cultural and societal norms that promote traditionalism and discourage questioning authority can also contribute to the development of cognitive rigidity.

Life Experiences and Trauma: Adverse life experiences, such as trauma or significant stress, can lead to cognitive rigidity as a coping mechanism. Individuals who experience unpredictable or threatening environments may develop rigid thinking patterns as a way to create a sense of control and stability in their lives. Repeated exposure to situations where flexibility leads to negative outcomes can also reinforce rigid thinking.

Social and Cultural Factors: Culture plays a significant role in shaping cognitive styles. Societies that value tradition, hierarchy, and stability may foster cognitive rigidity in their members, while those that emphasize innovation, individualism, and critical thinking may encourage cognitive flexibility. Socialization within these cultural contexts reinforces certain cognitive styles.

- The Interplay Between Nature and Nurture

Gene-Environment Interaction: The interaction between genetic predispositions and environmental influences is crucial in determining the degree of cognitive rigidity. For example, a child with a genetic predisposition toward anxiety or cautiousness may become more cognitively rigid if raised in an environment that reinforces fear of change or uncertainty. Conversely, supportive and nurturing environments can mitigate the expression of genetic predispositions, encouraging greater cognitive flexibility even in those who might be biologically inclined toward rigidity.

Developmental Plasticity: The brain’s plasticity, especially during childhood, allows for significant influence from environmental factors. While genetic factors provide a baseline, the environment can either enhance or diminish cognitive rigidity. Experiences that challenge an individual to adapt, problem-solve, and consider multiple perspectives can lead to the development of cognitive flexibility, even in those with a natural inclination toward rigidity.

- Current Understanding

Balance of Influences: It’s difficult to pinpoint an exact percentage of how much cognitive rigidity is due to nature versus nurture, as the influence can vary widely among individuals. However, it is generally accepted that both genetic and environmental factors play substantial roles, with their relative contributions depending on specific circumstances.

Dynamic Interaction: The development of cognitive rigidity is best understood as a dynamic interaction between nature and nurture. An individual’s genetic makeup might predispose them to certain cognitive styles, but these predispositions can be shaped, reinforced, or mitigated by environmental influences throughout their life.

Cognitive rigidity is shaped by both genetic and environmental factors, with neither nature nor nurture solely determining the trait. Genetics may predispose individuals to certain temperaments or cognitive styles that lean toward rigidity, but environmental factors, such as parenting, education, cultural influences, and life experiences, significantly influence the degree to which these predispositions manifest. Understanding cognitive rigidity requires a nuanced approach that considers the complex and ongoing interaction between biological and environmental influences throughout an individual’s development.

Lastly, how should parents deal with sulking children at different stages of the child’s development? #

Dealing with sulking children requires different strategies at various stages of development, as children’s cognitive, emotional, and social capacities evolve over time. Here’s how parents might approach sulking behavior at different stages:

- Early Childhood (Ages 2-5)

Understanding the Behavior: At this stage, sulking is often a manifestation of a child’s limited ability to express emotions and frustration. They might sulk because they don’t yet have the vocabulary or emotional regulation skills to articulate what they’re feeling.

Responding with Empathy: Parents should approach sulking with empathy, acknowledging the child’s feelings without immediately trying to “fix” the situation. For example, saying, “I see that you’re upset because you didn’t get what you wanted” can help the child feel understood.

Encouraging Expression: Encourage the child to use words to express their feelings. Phrases like “Can you tell me what’s wrong?” or “How are you feeling?” can help children begin to articulate their emotions instead of sulking.

Setting Gentle Boundaries: While it’s important to acknowledge their feelings, it’s also crucial to set boundaries. Let the child know that sulking is okay, but that it’s important to talk about feelings when they’re ready. “It’s okay to be upset, and when you’re ready, we can talk about it.”

- Middle Childhood (Ages 6-12)

Recognizing the Purpose: During middle childhood, sulking might be more intentional, used as a way to communicate displeasure or to gain control. Children at this stage are more aware of their emotions but might still struggle with expressing them in a socially acceptable way.

Promoting Problem-Solving: Encourage children to solve the problem that’s causing them to sulk. Ask them what they think would make the situation better or how they might approach the problem differently next time. This helps them develop problem-solving skills and reduces reliance on sulking as a coping mechanism.

Modeling Healthy Emotional Expression: Parents should model how to express frustration or disappointment in a constructive way. This might involve saying, “I’m feeling frustrated because of this situation, but I think we can work together to fix it.”

Addressing the Behavior: It’s important to discuss the sulking behavior itself once the child has calmed down. Help them understand that while it’s okay to feel upset, sulking doesn’t help solve the problem. Encourage them to find more effective ways to communicate their feelings.

- Adolescence (Ages 13-18)

Understanding the Complexity: Adolescents may sulk due to the complex emotional and social challenges they face, such as peer pressure, identity formation, and increasing independence. Sulking can be a way to express resistance, assert autonomy, or communicate dissatisfaction without direct confrontation.

Encouraging Open Communication: Create an environment where the adolescent feels safe to express their feelings openly. Encourage them to talk about what’s bothering them, and listen without immediately offering solutions or dismissing their feelings. Statements like “I’m here to listen if you want to talk” can be effective.

Respecting Autonomy: Adolescents are testing boundaries and asserting independence. While it’s important to address sulking, it’s also crucial to respect their need for space. Allow them time to process their emotions but check in periodically to see if they’re ready to discuss what’s on their mind.

Promoting Emotional Intelligence: Help adolescents develop emotional intelligence by discussing the importance of recognizing and managing emotions. Engage them in conversations about how to handle difficult situations constructively, and encourage self-reflection on the outcomes of their behavior.

- General Strategies Across All Stages

Consistency and Patience: Regardless of age, it’s essential to be consistent in how you respond to sulking. Over time, this helps the child learn that while their feelings are valid, there are more effective ways to communicate and resolve issues.

Positive Reinforcement: Reinforce positive behavior by acknowledging and praising when the child handles disappointment or frustration in a constructive way. This could be as simple as saying, “I’m really proud of how you talked to me about what was bothering you.”

Avoiding Power Struggles: Sulking can sometimes lead to power struggles, especially with older children. It’s important not to engage in a battle of wills. Instead, calmly set expectations and let the child know that you’re ready to talk when they are.

Seeking Professional Support: If sulking becomes a persistent issue that affects the child’s well-being or relationships, it might be helpful to seek guidance from a child psychologist or counselor. This is particularly important if sulking is accompanied by other signs of emotional distress.

In conclusion, dealing with sulking requires an understanding of the child’s developmental stage and a balanced approach that combines empathy, communication, and boundary-setting. By addressing the underlying emotions and promoting healthier ways to express and manage feelings, parents can help their children develop emotional resilience and better interpersonal skills.