Individuals have a better memory for tasks that are incomplete or interrupted compared to those that are completed.

Individuals have a better memory for tasks that are incomplete or interrupted compared to those that are completed.

The Zeigarnik Effect #

Why do we lose sense of time while we are sleeping? #

The phenomenon of losing a sense of time during sleep is intricately linked to the complex processes governing brain function and consciousness. Sleep is characterized by distinct cycles, including rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM stages, each associated with different brain activities and functions. The temporal disorientation experienced upon awakening can be attributed to several factors, both neurobiological and psychological, which I’ll explore in detail.

Neurobiological Perspectives #

Suppression of the Default Mode Network (DMN): The DMN is a network of brain regions that is active when one is at rest and not focused on the external environment. It’s associated with self-referential thoughts and the perception of time. During most stages of sleep, especially in non-REM sleep, the activity within the DMN is reduced, which could contribute to the diminished sense of time.

Altered Neural Connectivity: Sleep involves significant changes in brain connectivity. The communication between the frontal cortex, responsible for reasoning and executive function, and other areas of the brain is diminished. This reduced interaction impairs our brain’s ability to process and perceive time in the manner it does while awake.

Chemical Changes: Sleep modulates the levels of various neurotransmitters that influence our perception of time. For instance, the production of melatonin, which helps regulate sleep-wake cycles, can alter time perception by affecting the speed at which we process information.

Psychological Perspectives #

Lack of Sensory Input: During sleep, especially in the deeper stages, our brain essentially “disconnects” from the external sensory inputs that usually help us gauge the passage of time. Without these cues, such as changes in light or sound, our internal clock loses its reference points, leading to a distorted perception of time.

Memory Processing: Sleep plays a critical role in memory consolidation. The way we process memories during sleep, particularly during REM stages, can influence our perception of time. The disjointed and often non-linear nature of dreams can further distort our sense of time, making it difficult to distinguish between lengthy and brief dream episodes.

Cognitive Unawareness: The conscious awareness required to track time is largely inactive during most sleep phases. This lack of consciousness means that we’re not actively noting the passage of time, leading to a sensation of time either standing still or passing at an altered rate upon waking.

Integrating Perspectives #

The interplay between these neurobiological and psychological factors creates a scenario where the perception of time is fundamentally altered during sleep. Our brain enters a state that is radically different from wakefulness, where the usual markers and mechanisms for tracking time are offline or functioning in an altered state. Upon awakening, the re-engagement with our environment and the return of sensory inputs help recalibrate our sense of time, although often with a momentary disorientation as we adjust from the timeless realm of sleep to the temporally structured reality of wakefulness.

In summary, the loss of time sense during sleep is a multifaceted phenomenon, deeply embedded in the brain’s altered state of consciousness and functioning during this restorative period. It reflects the intricate relationship between brain activity, consciousness, and the perception of time, offering a fascinating insight into the complexities of human cognition and brain function.

Do some people retain the sense of time while they sleep, how do we explain waking up naturally just before the alarm clock goes of? #

Indeed, the phenomenon where individuals wake up moments before their alarm clock is set to go off suggests that, on some level, the brain maintains an awareness of time during sleep. This ability is an interplay of the body’s internal clock—the circadian rhythm—and the sleep-wake homeostasis, which together regulate sleep patterns and wakefulness. The mechanisms behind this intriguing ability involve a combination of biological and psychological factors.

Circadian Rhythm and Sleep-Wake Homeostasis

Circadian Rhythm: This is the body’s internal clock that operates on roughly a 24-hour cycle. It regulates physiological processes, including the sleep-wake cycle, hormone production, and body temperature. Circadian rhythms are influenced by external cues like light and darkness, which help synchronize the body’s clock to the environment. This internal timing mechanism enables the brain to track the passage of day and night, influencing when we feel alert or sleepy.

Sleep-Wake Homeostasis: This system keeps track of the need for sleep based on how long a person has been awake. The longer one is awake, the stronger the drive for sleep becomes, and vice versa. It helps balance sleep and wakefulness over time, ensuring that the body gets the rest it needs to function optimally.

Anticipation and Learned Behavior #

The ability to wake up just before an alarm clock goes off can also be attributed to a form of learned behavior or conditioning. If an individual habitually wakes up at the same time every day, the body’s internal clock adjusts to this pattern. The brain anticipates the upcoming alarm and initiates wakefulness processes ahead of it. This anticipation is facilitated by an increase in hormones like cortisol, which prepares the body for waking.

The Role of the Hypothalamus #

The hypothalamus plays a crucial role in both the circadian rhythm and the sleep-wake homeostasis. It processes environmental cues and regulates the release of hormones that affect sleep and wakefulness. The hypothalamus helps align the body’s internal clock with its external environment, enabling precise regulation of sleep patterns, including the timing of waking up.

The Zeigarnik Effect in Sleep #

Some psychological theories suggest that unfinished tasks or strong motivations can influence our wakefulness. The Zeigarnik Effect, for instance, posits that people remember uncompleted or interrupted tasks better than completed ones. Applied to sleep, this could mean that the brain’s preoccupation with the need to wake up at a specific time (an “unfinished task”) can contribute to the ability to wake up just before an alarm.

Neural Mechanisms #

Neurologically, certain brain structures, including the brainstem, regulate the transition between sleep and wake states. These structures respond to internal and external cues to initiate wakefulness. The exact neural pathways and how they interact with the circadian rhythm and sleep-wake homeostasis to facilitate waking up at a specific time remain areas of active research.

In conclusion, while the sense of time during sleep might be attenuated, it is not entirely lost. The body’s internal mechanisms, particularly the circadian rhythm and sleep-wake homeostasis, play a significant role in maintaining a rough awareness of time. This, coupled with learned behavior and psychological anticipation, can explain the phenomenon of waking up just before an alarm. These processes illustrate the remarkable adaptability and precision of the human body’s regulatory systems in managing sleep and wakefulness.

Tell me more about the Zeigarnik Effect? #

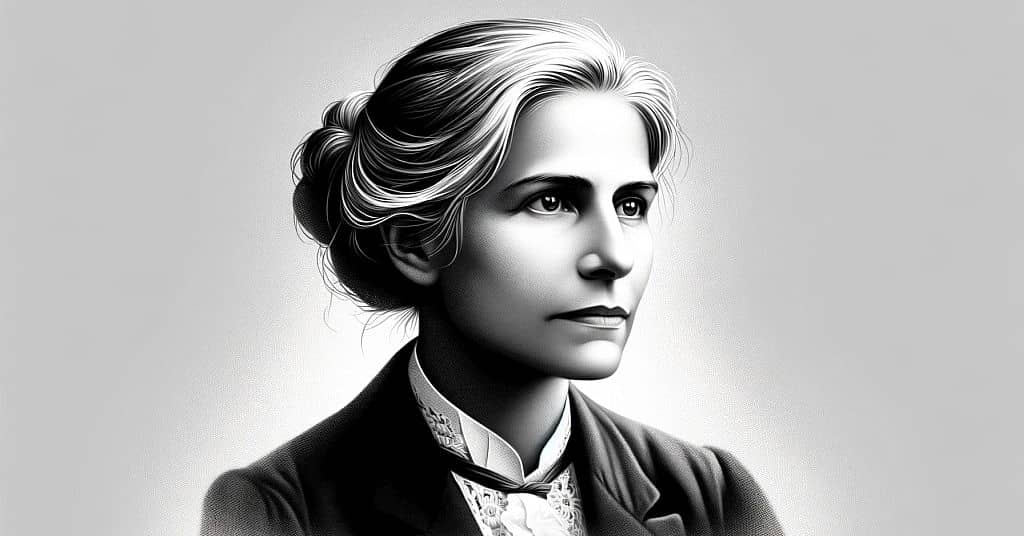

The Zeigarnik Effect is a psychological phenomenon named after the Soviet psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik, who first documented it in the 1920s under the supervision of Gestalt psychologist Kurt Lewin. Zeigarnik noticed that waiters seemed to have better recollections of unpaid orders than those that had been paid for and settled. Intrigued by this observation, she conducted a series of experiments to explore the phenomenon further. Her research revealed that individuals have a better memory for tasks or events that are incomplete or interrupted compared to those that are completed.

Fundamental Principles #

The Zeigarnik Effect rests on two fundamental principles:

Memory and Attention: It suggests that unfinished tasks create a state of cognitive tension or unease, which results in the task remaining more active in our memory. This cognitive tension acts as a psychological reminder that the task needs to be completed, leading to increased mental accessibility and recall.

Motivation and Closure: The effect is also interpreted through the lens of motivation for closure and resolution. The discomfort associated with unfinished tasks drives individuals to return to and complete those tasks, seeking psychological relief and closure.

Applications and Implications #

Task Management and Productivity: The Zeigarnik Effect has been applied to understand and improve task management and productivity. The notion that people are more likely to remember and complete interrupted tasks can be used to design better work and study schedules. Breaking down tasks into smaller, manageable parts that can be “interrupted” may enhance motivation and efficiency.

Advertising and Storytelling: In advertising and storytelling, creating narratives or messages that are incomplete or that end on a cliffhanger can increase audience retention and engagement. The desire for closure compels the audience to return for resolution, a technique widely used in serial storytelling and marketing campaigns.

Learning and Education: Educators can leverage the Zeigarnik Effect by structuring learning activities that are interrupted and then resumed, potentially enhancing retention and engagement. This approach can help in designing curricula that maximize student engagement and memory retention.

Therapeutic Settings: Understanding the Zeigarnik Effect can also be beneficial in therapeutic settings, helping individuals deal with unresolved issues or tasks. Therapists might use it to help clients identify and prioritize unfinished tasks that are causing anxiety, employing strategies to either complete those tasks or come to terms with leaving them unresolved.

Criticisms and Limitations #

While the Zeigarnik Effect is a compelling concept, it has its criticisms and limitations. Some researchers have pointed out that the effect may not be universally applicable, with subsequent studies yielding mixed results. Factors such as task significance, individual differences in memory and motivation, and cultural variations can influence the strength and applicability of the Zeigarnik Effect. Moreover, the simplicity of the tasks used in Zeigarnik’s original experiments and the complexity of real-world tasks may account for variations in the effect’s observability.

In summary, the Zeigarnik Effect highlights the psychological impact of incomplete tasks on memory and motivation. While it offers valuable insights into human cognition and behavior, its application and significance can vary depending on context, task characteristics, and individual differences. Understanding these nuances can enhance its application across various domains, from education and psychology to marketing and organizational behavior.

Could Zeigarnik Effect apply to a music composition? #

Yes, the Zeigarnik Effect can apply to music composition in various intriguing ways, influencing both the creation process and the listener’s experience. In the context of music composition, this psychological phenomenon can manifest in the creative process, the structuring of musical pieces, and how audiences engage with and remember music.

In the Creative Process #

For composers and musicians, the Zeigarnik Effect suggests that an unfinished musical piece can remain more prominently in their thoughts, fostering a continuous engagement with the composition even when not actively working on it. This persistent cognitive presence can lead to a deeper contemplation of the piece, potentially enhancing creativity and problem-solving. Composers might find themselves subconsciously working through compositional challenges, leading to breakthroughs at unexpected moments. The cognitive tension associated with unfinished work could drive composers to return to their compositions with fresh ideas and perspectives, thereby facilitating the creative process.

Structuring Musical Pieces #

In the structuring of musical pieces, composers can intentionally employ the Zeigarnik Effect to enhance listener engagement and retention. By creating compositions with unresolved musical phrases, tension-building harmonies that do not resolve immediately, or interrupting a musical narrative before its climax, composers can keep listeners mentally engaged and longing for resolution. This technique can make the music more memorable and compelling, as the anticipation of resolution keeps the piece actively present in the listener’s mind.

Listener Engagement #

From the listener’s perspective, the Zeigarnik Effect can explain why certain pieces of music, especially those with unresolved or unexpected endings, remain in memory longer. The desire for closure and resolution in the musical narrative can create a lasting impression, prompting listeners to revisit the piece in hopes of finding resolution or to engage more deeply with the music to understand its complexities. This effect can be particularly pronounced in genres that often employ narrative or conceptual themes, such as classical music, progressive rock, or concept albums in popular music.

Enhancing Memorability and Emotional Impact #

Furthermore, the use of the Zeigarnik Effect in music composition can enhance the emotional impact of a piece. By manipulating listeners’ expectations and desires for resolution, composers can evoke stronger emotional responses. This technique can be seen in film scores and operas, where music plays a critical role in driving the narrative forward, often leaving themes unresolved until key narrative moments.

Limitations and Considerations #

However, it’s important to note that the effectiveness of the Zeigarnik Effect in music composition and listening experiences may vary based on individual listener sensitivities, cultural background, and personal preferences. What might be a compelling, unresolved musical question for one listener could be perceived as unsatisfying or frustrating by another.