An integrated self is likely to have a more nuanced and tolerant view of corruption.

An integrated self is likely to have a more nuanced and tolerant view of corruption.

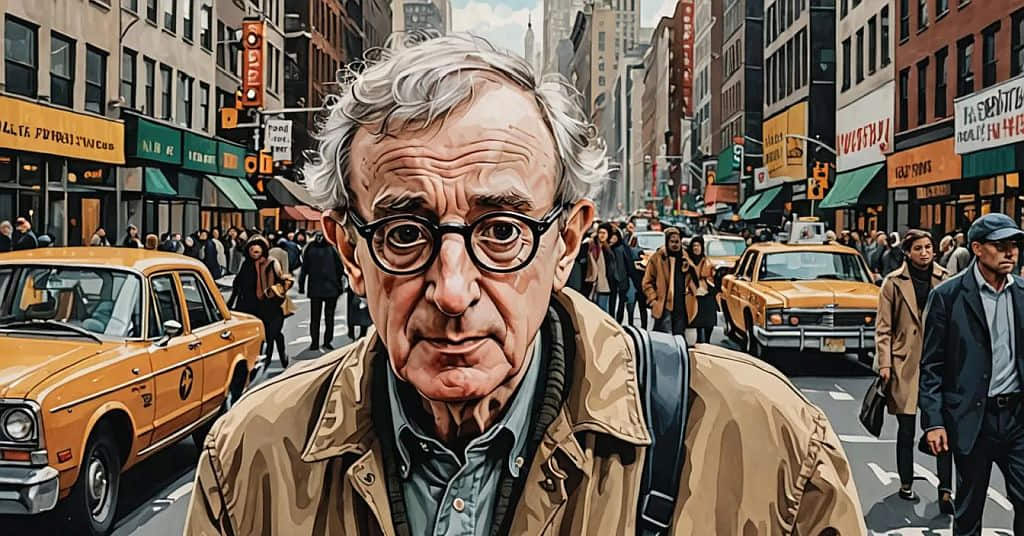

Woody Allen and Jung #

One of Woody Allen’s signature themes is the corruption temptation faced by ordinary people, ne? #

Indeed, the theme of corruption and the moral temptations faced by ordinary people is a recurring motif in Woody Allen’s oeuvre. Allen’s films often delve into the complexities of human nature, exploring how seemingly ordinary individuals grapple with ethical dilemmas, existential crises, and the darker aspects of their psyche. This thematic focus is evident in several of his works, where he portrays characters who confront moral corruption, often leading to dramatic or tragic outcomes.

For instance, in “Crimes and Misdemeanors” (1989), Allen examines the moral decay of Judah Rosenthal, a respected ophthalmologist who resorts to murder to resolve a personal crisis. The film juxtaposes Judah’s storyline with that of Clifford Stern, a documentary filmmaker facing his own ethical challenges, thus highlighting the contrasts between moral failure and integrity.

Similarly, “Match Point” (2005) explores themes of luck, fate, and moral compromise. The protagonist, Chris Wilton, an ambitious tennis instructor, finds himself entangled in an extramarital affair and eventually commits murder to preserve his social standing and secure his future. The film underscores the randomness of fate and the ease with which ordinary individuals can succumb to corrupt actions when driven by ambition and fear.

Another notable example is “Blue Jasmine” (2013), where the protagonist, Jasmine French, a former socialite, faces the consequences of her moral failings and the corrupt actions of her husband. The film portrays her descent into mental instability as she grapples with the loss of her wealth and status, emphasizing the fragility of human morality when confronted with the temptations of greed and dishonesty.

Allen’s films often blend dark humor with profound philosophical inquiries, making his exploration of corruption and temptation both intellectually stimulating and emotionally resonant. His characters are typically multi-dimensional, embodying the inherent contradictions of human nature, and his narratives frequently leave audiences pondering the complexities of ethical behavior in a morally ambiguous world. Through these stories, Allen effectively captures the universal struggle between integrity and corruption, illustrating how ordinary people can be tempted by and ultimately succumb to moral decay.

It seems, though, that the earthy rewards enticing corruption are always disproportionally more innocent compared to the consequences. Are we compelled to sympathise, rather than judge? #

Your observation is astute. Woody Allen’s portrayal of corruption often emphasizes the disproportionate nature of the rewards and consequences, thereby eliciting sympathy rather than judgment from the audience. This narrative technique is a hallmark of Allen’s storytelling, reflecting his nuanced understanding of human frailty and the often arbitrary nature of moral judgments.

In “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” for instance, Judah Rosenthal’s descent into moral corruption is driven by his desire to maintain his comfortable life and avoid the scandal that his affair would bring. The audience is made to understand his fear and desperation, even as they witness his abhorrent actions. The film’s philosophical undertone, particularly through the lens of Dostoevskian existentialism, questions the nature of morality and justice, making the audience ponder whether the cosmic or societal balance of justice will ever be restored.

Similarly, in “Match Point,” Chris Wilton’s actions are driven by his aspiration for social mobility and material comfort. The film meticulously builds his character, making the audience acutely aware of his internal struggles and the seeming inevitability of his choices. The randomness of fate, symbolized by the tennis ball hanging on the net, emphasizes the thin line between success and failure, guilt and innocence. Here, Allen suggests that the moral universe is indifferent to human actions, and thus, viewers are led to empathize with Chris’s plight rather than purely condemn him.

In “Blue Jasmine,” Jasmine French’s plight evokes sympathy because her descent into mental instability and social ruin is depicted with a deep sense of pathos. Her actions and delusions are portrayed as tragic flaws rather than outright malevolence, leading the audience to see her as a victim of her circumstances and her own psychological fragility. The film’s exploration of her vulnerability and the harsh consequences she faces encourages empathy rather than moral condemnation.

Allen’s ability to evoke sympathy for characters who commit morally questionable acts underscores his belief in the complexity of human nature. By highlighting the often disproportionate rewards that tempt individuals into corruption and the severe consequences that follow, Allen forces the audience to confront the inherent contradictions and ambiguities of moral behavior. This approach not only humanizes his characters but also challenges the audience to reflect on their own moral compass and the societal structures that shape ethical decisions.

In essence, Allen’s films encourage a deeper understanding of the human condition, suggesting that moral failings are often a product of circumstantial pressures and inherent weaknesses rather than purely malevolent intentions. This nuanced portrayal fosters a sense of empathy and introspection, compelling the audience to sympathize with the characters’ struggles rather than judge them harshly.

In another context, a strong moral compass may require disowned parts of self (Jungian shadow) - does it follow that an integrated self would be more tolerant of corruption? #

The concept of the Jungian shadow is indeed relevant when considering the relationship between a strong moral compass and susceptibility to corruption. According to Carl Jung, the shadow encompasses the parts of the self that are repressed or denied because they are considered undesirable or incompatible with one’s conscious self-image. These disowned parts of the self can include instincts, desires, and traits that an individual deems unacceptable.

Jungian psychology posits that integrating the shadow involves acknowledging and accepting these repressed aspects of the self, leading to greater psychological wholeness and self-awareness. This integration does not mean acting out all shadow impulses but rather recognizing them and understanding their influence on one’s behavior and thoughts. An integrated self, therefore, is more conscious of its full range of motivations and potentialities.

Given this framework, one could argue that an integrated self might indeed be more tolerant of corruption in the sense of being more aware of and accepting the existence of morally ambiguous impulses within themselves. This awareness can lead to a more nuanced understanding of human behavior, including one’s own capacity for both good and evil. However, whether this tolerance translates into a greater likelihood of engaging in corrupt behavior is more complex and context-dependent.

Self-Awareness and Moral Decisions: An integrated individual might possess greater self-awareness and therefore make more deliberate moral choices. Understanding their shadow allows them to recognize and manage their impulses, potentially leading to more ethical behavior. For instance, they might be better equipped to foresee the consequences of their actions and resist temptations that could lead to corruption.

Compassion and Empathy: Integration of the shadow can foster greater compassion and empathy for oneself and others. Recognizing one’s own flaws and vulnerabilities can lead to a more empathetic view of others’ moral struggles. This might make them more tolerant and understanding of others’ moral failings without necessarily condoning corrupt behavior.

Moral Flexibility vs. Rigid Morality: A strong, unexamined moral compass might lead to rigid moral absolutism, where any deviation from prescribed norms is harshly judged. An integrated self, by contrast, might adopt a more relativistic or situational approach to ethics, understanding that moral decisions often involve complex trade-offs. This flexibility can be a double-edged sword, potentially leading to more pragmatic but ethically ambiguous decisions.

Resilience Against Corruption: Awareness of one’s shadow might also make one more resilient against external pressures to engage in corrupt behavior. Understanding one’s own vulnerabilities can help in devising strategies to counteract temptations and maintain integrity in challenging situations.

In conclusion, an integrated self is likely to have a more nuanced and tolerant view of corruption, recognizing the complexities and contradictions inherent in human nature. This does not necessarily mean that they would be more likely to engage in corrupt behavior, but rather that they might approach ethical dilemmas with a deeper understanding of the factors at play. The integration of the shadow can thus lead to a more holistic and balanced approach to morality, where ethical decisions are made with a full awareness of one’s inner landscape and the potential for both light and dark within.